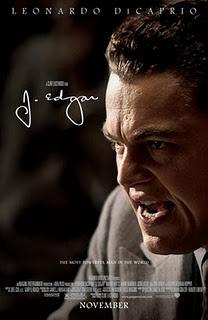

J. Edgar is a film about a legend who cared only for respect, made by a man who seems to care only for awards. Clint Eastwood, the most shameless Oscar-baiter currently working, has nothing to say about J. Edgar Hoover, infamous founder of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, nor does he even try to tell his deflated narrative well. This is painting-by-numbers biopic, not even its limp "twist" subverting its schematic use of flashbacks and theme-articulating moments in twilight years. Judging from the mixed reception J. Edgar received, however, Eastwood's increasingly stale approach might finally be rubbing critics the wrong way.

J. Edgar is a film about a legend who cared only for respect, made by a man who seems to care only for awards. Clint Eastwood, the most shameless Oscar-baiter currently working, has nothing to say about J. Edgar Hoover, infamous founder of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, nor does he even try to tell his deflated narrative well. This is painting-by-numbers biopic, not even its limp "twist" subverting its schematic use of flashbacks and theme-articulating moments in twilight years. Judging from the mixed reception J. Edgar received, however, Eastwood's increasingly stale approach might finally be rubbing critics the wrong way.Written by Dustin Lance Black, J. Edgar lacks the passion the writer brought to his script for Milk. One can understand his more ambiguous feelings toward Hoover, but Black finds himself caught between sympathy for the man and clearly critical thoughts on his seedier tactics, and his own mixed thoughts inform the film's presentation of its protagonist. If you think Hoover's brand of "keeping us safe" justice is something this country could use again, you'll be disappointed by its depictions of Hoover's egomaniacal shadow takeover of government. If you see Hoover as the precursor to Patriot Act politics of paranoia and fear, you'll hate its attempts to make an unpleasant man sympathetic. But don't make the mistake of thinking this lack of extremes means that Hoover emerges a rounded, complex human being. Instead, he serves as a repository for lazy screenwriting summaries of character, and Eastwood, famously lazy when it comes to fixing the drafts he's given, does nothing to alleviate the hollow revelations of J. Edgar's character.

One could argue that, given this is a film about Hoover trying to erect his own deluded self-image as legion, the fact that no one in this film never looks his or her intended age is a wry visual commentary. But that ignores Eastwood's status as a no-nonsense workman, and one glimpse at Leonardo DiCaprio earnestly trying to look 24 dispels any notion of play. To fit DiCaprio's middle age, Eastwood has to overemphasize his grim, joyless color palette even during Hoover's ascendancy. The director's modern output has generally been sapped of its pigment, but J. Edgar takes the desaturation to absurd new lows. Everything here looks rubbed down with ash, with such errant use of shadow that evocative use of shadow takes a back seat to mere incoherence.

Nevertheless, DiCaprio gives it his all as Hoover, valiantly working against a leaden script and (in Hoover's old age) cocooning latex makeup in a futile search for complexity. Two things set Hoover's tongue uncontrollably wagging: sex and justice. The former makes him stammer with nervosa (even revulsion), the latter with unchecked excitement at the prospect of fighting enemies. When the lad rushes to the scene of an anarchist bombing on the attorney general in 1919, his determination masks a sense of relieved satisfaction, his paranoid fears of radicals finally confirmed. DiCaprio never delves into the depths of Hoover's fears and vendettas, but he nearly captures the contradictions of the G-man, finding the personality link between the fearlessness of walking into the Oval Office every few years to blackmail a new president and the quivering shyness that comes with being asked for an innocent dance.

DiCaprio certainly escapes the tedium of Black's script with more aplomb than any of the other principal cast. Naomi Watts arrives early as Helen Gantry, the secretary who served under Hoover nearly all of his professional life, but she has nothing to do except follow orders with only the rarest suggestion of unease, which barely registers at the level of seeing someone put a drink on a table without a coaster. Poor Armie Hammer has it worst of all. Playing Hoover's second-in-command (and rumored lover) Clyde Tolson, Hammer does not have the luxury of portraying a human being. As a strapping young lad, he is the projection of Hoover's clear homosexual fantasies: a clean-cut, well-tailored man who makes catty comments about fashion and will also make the first move Edgar is too terrified to pull. As an aged, disillusioned agent, Hammer sports some of the most hysterically bad makeup it's impossible not to feel sorry for him. He looks as if someone used his face to scrape the spackle off a putty knife, latex flesh hanging off him in tumorous clumps.

But damn it, Edgar still loves him, and anyone who takes this film as remotely true to Hoover's life will be flummoxed as to how the man could intimidate anyone with his career-killing secret so plainly visible. The relationship of the two men is chaste, but Black still devotes huge portions of the film to the sexual tension between the two men, even as he isolates it from relevance to the rest of the story. He does not, for example, even float the idea that Hoover's latent homosexuality might have been a motivating force in his obsessive quest for shameful dirt on others. And this is from Black, who had no trouble whatsoever suggesting that such self-loathing was not merely a factor but the factor in Dan White's assassination of Harvey Milk. Instead, we are treated to the almost comical sight of Hoover's mother (Judi Dench), a domineering wench who speaks solely in dolorous thuds of guilt inducement. She even addresses her son's all-but-open sexuality by darkly reminding him of a cross-dresser in their town they called a "daffodil," a word said with hilariously misplaced gravity.

The mother becomes just one more haphazardly inserted element in the film's incessant leaps between desperate grabs for thematic purpose. An amusing split between the director's and writer's age sensibilities come into play here highlights the problem: Eastwood thinks he's making Citizen Kane, the story of how a man's grasp on the American Dream later becomes a chokehold that forces out the grotesquerie of what he loves. Black, on the other hand, is looking to one of that film's clearest progeny, The Social Network, which works on a smaller scale yet aims even higher, seeking to precede Kane by showing how such creation myths as the American Dream begin. J. Edgar thus tries to be both, but in treating Hoover as the product of his own creation myth, the film betrays an unwillingness to either straighten out the inconsistencies in vision or to pursue this ouroboric theme to its ambitious conclusion.

As such, J. Edgar is but the latest film to embody the detached laconicism of Eastwood's actor persona. For all his formal chops, Eastwood seems increasingly indifferent to the quality of his own work even as almost everything he does feels cynically calculated to get some tacky statue. His last film, the even more dismal Hereafter, boasted some truly awful moments of crystallized directorial laziness, embarrassingly simple mistakes a man of Eastwood's stature and age should not have made. J. Edgar has one such moment in a flashback to a horse race where Edgar and Clyde bonded, or at least, that's intended to be the focus of the shot. My attention was directed to what the camera itself was focused on, which is to say, the railing in front of every human being in the shot. This is a blunder I expect a sandals-and-black-socks-wearing father with a Flip cam shooting the family vacation to make, not Eastwood and his cinematographer Tom Stern. And for the love of God, will someone stop letting him make his own scores? His wretchedly plodding piano notes sound less like an evocation of Hoover's inner pain than a drunk slowly pounding the same four keys in a stupor.

Hereafter was spectacularly bad, but J. Edgar feels like every issue I've had with late-career Eastwood—weak script, formalism so stiff it's banal, an overinflated sense of importance—put into one film. The best I can say for it is that, while taking everything else from Changeling, at least the movie didn't port over that film's overwrought melodrama. But I might have actually liked some more weeping and shrieking, if only to wake up the audience. As the story of a man's life, J. Edgar fails miserably. As a thematic statement on how a man chased the idea of America with such force that he actually corrupted the very ideal he wished to embody, it fares even worse. Sporting the worst framing device since Saving Private Ryan, turgid cinematography, and actors left without a clue how to progress, J. Edgar proves so dull one cannot even say it spins its wheels. Hell, it doesn't even shift out of park.