Amsterdam, Netherlands - April, 2017: Visitors watching ‘The Night Watch,’ Rembrandt’s largest and most famous painting in Rijksmuseum’s Gallery. (Shutterstock) Among Dutch-speaking art lovers, 2019 is known as a Rembrandt-jaar (Rembrandt year), one marking the 350th anniversary of the death of the artist Rembrandt van Rijn. It is the cause for the beloved artist — who painted in the 1600s — to be commemorated with exhibitions, publications and even delicious treats.

Amsterdam, Netherlands - April, 2017: Visitors watching ‘The Night Watch,’ Rembrandt’s largest and most famous painting in Rijksmuseum’s Gallery. (Shutterstock) Among Dutch-speaking art lovers, 2019 is known as a Rembrandt-jaar (Rembrandt year), one marking the 350th anniversary of the death of the artist Rembrandt van Rijn. It is the cause for the beloved artist — who painted in the 1600s — to be commemorated with exhibitions, publications and even delicious treats. A milestone Rembrandt year occurred 13 years ago, with the fourth centenary of his birth. The worldwide professional organization of curators of Dutch and Flemish art, CODART, recorded 83 exhibitions between 2005 and 2007 in honour of that Rembrandt year.

And, yet, with the 2006 Rembrandt-jaar still fresh in the memories of many, one may wonder, why are we celebrating Rembrandt again? What appeal does this European male artist have for us in 2019?

The Rembrandt years

Amy Golahny, Richmond Professor of Art History Emerita at Lycoming College, describes the 2006 exhibitions as focused on newly discovered documents and the contextualization of the master within the economic, diplomatic and historical role of art. One consequence of this year was the increase in monographic exhibitions of art by those in Rembrandt’s orbit, such as his master Pieter Lastman and his colleague and a competitor Jan Lievens.A substantial 53 shows dedicated to the artist are listed on the CODART web site this year. These include Leiden circa 1630: Rembrandt Emerges, organized and circulated by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre of Queen’s University, where I am a curator and resident researcher. The show focuses on the development of Rembrandt’s pictorial language among a network of colleagues in his native city of Leiden.

The Next Rembrandt: Blurring the boundaries between art and technology: the challenge to see if Rembrandt could brought to digital life to create a new painting. The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the foremost collection of Rembrandt’s art in the world, took a broader perspective in All the Rembrandts, which showcased its holdings of 20 paintings, 60 drawings and 300 of the finest impressions of the artist’s prints. From examinations of Rembrandt’s early years to a comprehensive view of his accomplishments across media, this year’s exhibitions delve deeply into the development of this singular artistic personality.The earliest Rembrandt year seems to have been 1906, the 300th anniversary of his birth. That year spurred the placement of a commemorative plaque on the site of his birth home and the erection of a sculpted likeness in Leiden, as well as the purchase of the artist’s home on the Breestraat in Amsterdam to create a museum.

These early acts were as much monuments to the man as much as to his oeuvre, which reveal the lingering 19th-century romanticization of the artist as a Dutch national hero. Subsequent Rembrandt years — 1956 and 1969 — have concentrated on bringing together masterpieces by Rembrandt and his pupils so as to further delineate their individual oeuvres.

In anticipation of the 1969 Rembrandt year, the Rembrandt Research Project, which became the authoritative voice in determining the authenticity of Rembrandt paintings, was founded. Clearly, these commemorative years have had a huge impact upon our understanding the artist’s oeuvre and his biography.

The artist

Rembrandt van Rijn, ‘Self-Portrait’, around 1629, oil on panel (Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Courtesy of The Clowes Fund, C10063.) There is a rich body of period documents that convey the painter’s character. Authors frame his personality as one rooted in a sense of conviction and autonomy and he seems to have experienced many of the trials and tribulations of modern life.

Rembrandt van Rijn, ‘Self-Portrait’, around 1629, oil on panel (Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Courtesy of The Clowes Fund, C10063.) There is a rich body of period documents that convey the painter’s character. Authors frame his personality as one rooted in a sense of conviction and autonomy and he seems to have experienced many of the trials and tribulations of modern life.He was a late bloomer, and began his art education at the late age of fifteen or so; he believed so audaciously in his own skills that he proclaimed he could sell an unsatisfactory commission depicting a man’s beloved to any interested buyer.

After the death of the love of his life, he took up with the nursemaid and, subsequently, the housekeeper, with whom he had a child out of wedlock. He declared insolvency after unwise financial decisions.

There is something perpetually intriguing about his depiction of the human condition. His powerful colour, robust forms and imaginative interpretations humanize familiar narratives in striking ways. His early masterpiece, Judas Returning the Thirty Pieces of Silver of around 1629, for example, communicates the physical burden of treachery in horrifying terms: clothing rent in desperation, scalp bleeding after a violent fit, hands clasped in agony, body contorted in humiliation and despair.

Rembrandt van Rijn, ‘Judas Returning the Thirty Pieces of Silver’, around 1629, oil on panel (Private collection. Morgan Library & Museum/Private Collection) Many scholars; numerous creative endeavours like novels, movies and works of art; and even new applications of technology.

Rembrandt van Rijn, ‘Judas Returning the Thirty Pieces of Silver’, around 1629, oil on panel (Private collection. Morgan Library & Museum/Private Collection) Many scholars; numerous creative endeavours like novels, movies and works of art; and even new applications of technology. Rembrandt, through his acute observation of the human condition, has incited new reflections upon our place in the world and our contributions to it.

The shows

Why have museum exhibitions been so fundamental to this investigation of Rembrandt?The curatorial act is a powerful strategy for imbuing the Old Masters with agency in the modern world. That act can unify contemporary themes with historical grounding, inviting the viewer to consider artworks as living objects bearing renewed meaning through the interpretative material presented in the gallery. The curatorial act can also invoke deeper understanding through comparison with other objects, illuminating new perspectives on familiar works.

Curators, as stewards of collections, have the responsibility to think creatively and broadly about the current pertinence of historical artworks. This can be seen in some of this year’s Rembrandt exhibitions.

We are delighted today to launch a call for artists to participate in an exhibition celebrating 350 years since #Dutch master artist #Rembrandt van Rijn died. ‘Rembrandt@350: Zimbabwe remasters a Dutch icon’. Launch in both #Bulawayo & #Harare with @BYOgallery & @NatGalleryZimb. pic.twitter.com/HBM0gFaCja— Dutch Embassy Harare 🇳🇱 (@NLinZimbabwe) August 2, 2019

The exhibitions on view this year demonstrate that new perspectives can deepen our access to and appreciation of the past. Each era curates the Rembrandt that it desires.

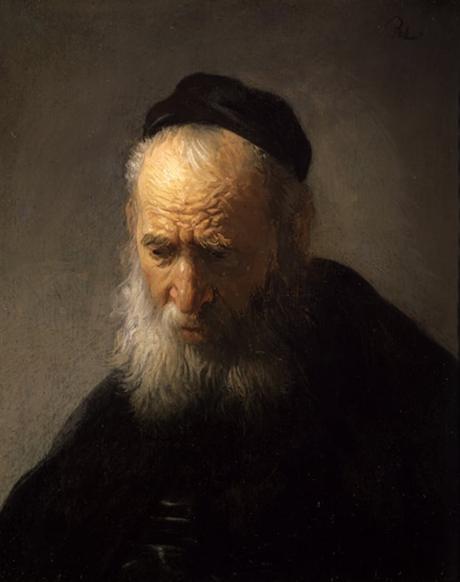

So, in this Rembrandt year of 2019, how are you celebrating the master? Rembrandt van Rijn, ‘Head of an Old Man in a Cap c. 1630, oil on panel. (John Glembin/Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen's University. Gift of Alfred and Isabel Bader, 2003)

Rembrandt van Rijn, ‘Head of an Old Man in a Cap c. 1630, oil on panel. (John Glembin/Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen's University. Gift of Alfred and Isabel Bader, 2003) About Today's Contributor:

Jacquelyn N. Coutré, Bader Curator/Adjunct Assistant Professor, European Art, Queen's University, OntarioThis article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.