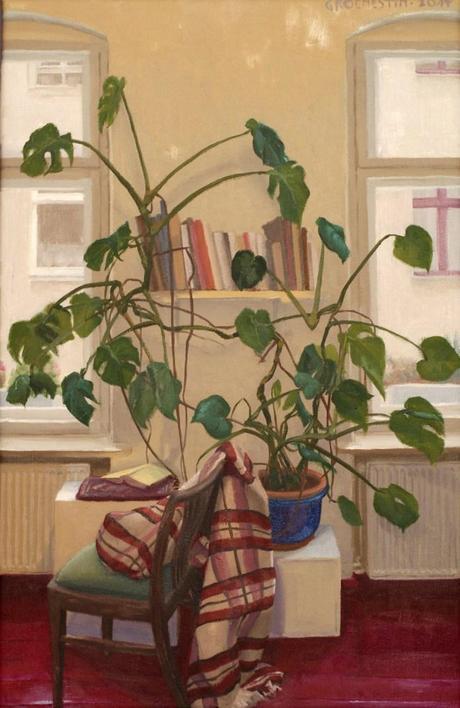

It’s taking over everything © Samantha Groenestyn (oil on linen)

Based purely on observation and my own experiences and without recourse to hard research, I’ve come to hold the wholly unfeminist view that men are, generally speaking, better at things than women. I certainly don’t want to make any normative claims that things ought to be this way, but since these observations have troubled me my entire life, and have sometimes made me feel without hope due to some seemingly inbuilt inferiority, I simply want to speculate about why this might be.

Christ Church, Oxford

And I wouldn’t be the first. Virginia Woolf meanders through a very persuasive line of reasoning, narrated through her wanderings as a guest through the ‘courts and quadrangles of Oxbridge on a fine October morning,’ much as I found myself this past October. ‘Intellectual freedom depends upon material things,’ she argues (1928: 106).

‘Poetry depends upon intellectual freedom. And women have always been poor, not for two hundred years merely, but from the beginning of time. Women have had less intellectual freedom than the sons of Athenian slaves. Women, then, have not had a dog’s chance of writing poetry. That is why I have laid so much stress on money and a room of one’s own.’

And while I certainly do not disagree with her thesis, I want to build on it and offer an idea of my own. This being that, perhaps due to greater material liberties, perhaps due to the way they are encouraged to explore and not taught to everywhere be cautious, afraid and compliant, boys learn in a fundamentally different way to girls. And they learn more thoroughly, more single-mindedly, and more carried by their own wilful curiosity even if it drives them beyond the accepted bounds of education.

Oxford

It is no secret that girls, only recently permitted an education, are performing better in schools than boys. But our education system does not, if I might make so bold a claim, encourage greatness. Instead it asks for compliance, adherence to curricula, and measurable aptitude through examinations. I was an excellent student in both school and university, often triumphing over the very boys I looked up to. I was willing to accept the terms of the game, and perform the requisite tasks to receive the desired praise. A boy I particularly admired—Billy—gave approximately zero fucks. We had a beautiful symbiosis: I sat next to him in physics, listened attentively to the teacher while Billy drew or made jokes, and then I brought all my questions to Billy. And he furnished me with every answer, with insightful explanations, demonstrations and a depth of understanding that absolutely dazzled me.

Bodleian Library, Oxford

School was a magical place to me, where there was a library and people who set aside time to impart their knowledge to me, knowledge I was hungry for but did not know how to access. School was, I’ve no doubt, infinitely boring for Billy, except for getting to sit next to girls like me, because all of his learning took place outside of school. When I realised this, it blew my mind. School seemed a holy sanctuary of knowledge; Billy taught me (among wave theory, additive and subtractive colour and how to calculate trajectories, Simpsons jokes interspersed) that school barely skimmed the tip of the iceberg and that our teachers were cruelly holding out on us. He had university textbooks at home, and did all the calculations during the summer holidays, and learned a great deal from the mistress of experience, thanks to his mother allowing him to blow things up in the backyard.

Girls have adapted to the education system because we are extremely good at being submissive and we care how people measure us. We are well-trained since birth, since the dawn of time, to obey instructions and meet requirements. We excel in this for we are ever conscious of how others perceive us—our hair, our gestures, our conversation. School is merely another form of etiquette, and we fit its rigid confines comfortably. Yet despite the academic success of girls, it’s also no secret that men remain at the top of just about every imaginable field. Women can demonstrate understanding of taught concepts, but we are stunted as innovators.

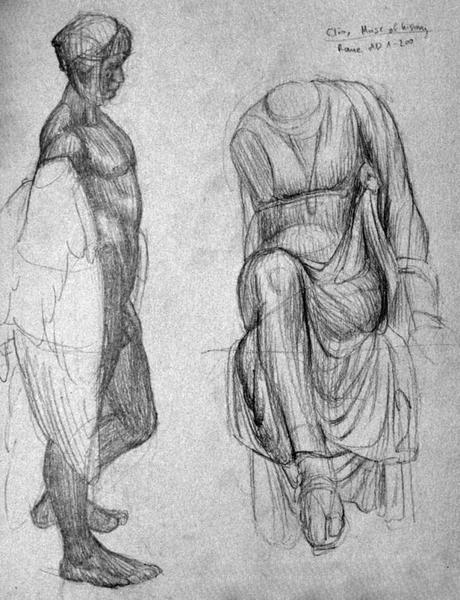

Copies after Sir Alfred Gilbert, Icarus, and the Roman Clio, muse of history, The Ashmolean, Oxford

True genius depends on making leaps, taking risks, and working doggedly at a single problem in the face of sustained criticism. It requires a degree of madness: obsession, single-mindedness, anti-social tendencies that compel one to stay home of a Friday night solving a problem that matters to no one else. These traits are—I don’t pretend to know why, or to claim that this is necessarily genetic—characteristically masculine. It’s unladylike to grow your armpit hair or to express left-of-field ideas. Our mental states are as groomed as our hairless skin. I want to suggest we ought to let them grow wild as our brothers do: assuming nothing, open to new concepts, and fearlessly tackling them with reason. Let us remain so madly fixated upon our tasks that we, too, become impervious to attacks on ourselves, and engage only with those relevant to our work.

I’m reminded of the fearful all-consuming passion of a male character described by the undeniably brilliant Mary Shelley (2008: 29):

‘Even at that time I shuddered at the picture he drew of his passions: he had the imagination of a poet, and when he described the whirlwind that then tore his feelings he gave his words the impress of life so vividly that I believed while I trembled. I wondered how he could ever again have entered into the offices of life after his wild thoughts seemed to have given him affinity with the unearthly; while he spoke so tremendous were the ideas which he conveyed that it appeared as if the human heart were far too bounded for their conception. His feelings seemed better fitted for a spirit whose habitation is the earthquake and the volcano than for one confined to a mortal body and human lineaments.’

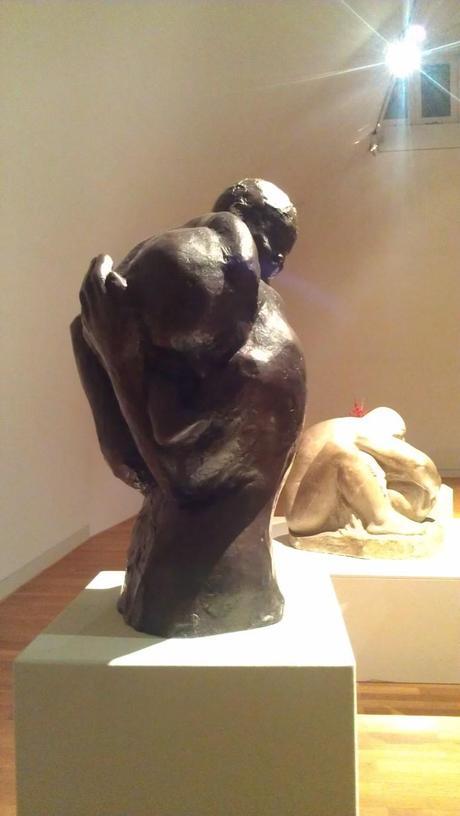

Mutter mit Kind über der Schulter (1917) by Käthe Kollwitz, Berlin

Käthe Kollwitz, an unquestionably brilliant German draughtsman and sculptor, shares some insightful observations in her achingly beautiful diaries on her unlikely artistic development and the falling away of many of her female contemporaries, her own sister Lise included. ‘Actually,’ she writes of Lise (1988: 80),

‘she is more talented artistically. That shows up to this day. But she lacked training. And something else too, perhaps: my guess is that she has lived less intensively. When she was young she cultivated herself and the objects of her love. That was enough for her. I probably had more drive. And it has been this drive alone which has made it possible for me to develop as far as possible my talent, which in itself is inferior to hers.’

Mutter mit totem Sohn (Pietà) by Käthe Kollwitz, Berlin

And, more strongly (p. 24-5):

‘Now when I ask myself why Lise, for all her talent, did not become a real artist, but only a highly gifted dilettante, the reason is clear to me. I was keenly ambitious and Lise was not. I wanted to and Lise did not. I had a clear aim and direction. … But she was gentle and unselfish. (‘Lise will always sacrifice herself,’ Father used to say.) And so her talent was not developed. … She lacked total concentration upon it. I wanted my education to be in art alone. If I could, I would have saved all my intellectual powers and turned them exclusively to use in my art, so that this flame alone would burn brightly.’

Mutter mit totem Sohn (Pietà) by Käthe Kollwitz, Berlin

I want to suggest, along with Kollwitz (p. 23), that ‘the tinge of masculinity within me helped me in my work’—and that in order to reach these heights of brilliance, with the Mary Shelleys, Virginia Woolfs and Käthe Kollwitzes of the world, we must follow the man inside us and adapt the way that we choose to learn. We must set ourselves tasks, ignore external measures, walk away from outside demands. We must not think of ourselves at all, but solely of the work, and abandon all else that distracts us. We must simplify our lives and allow ourselves to be absorbed and consumed with our occupation. Let us turn away from superficial praise; true respect comes with real accomplishment.

For even Virginia Woolf (1928: 98) breathes a sigh of relief at the substance of men’s work: ‘Indeed, it was delightful to read a man’s writing again. It was so direct, so straightforward after the writing of women. It indicated such freedom of mind, such liberty of person, such confidence in himself.’ I in fact don’t think that women need be inferior—and Woolf, Shelley and Kollwitz present dazzling lady counterexamples. I only think that we need to identify where we are causing ourselves to stumble, for these are obstacles that we can remove. Let us not sacrifice ourselves with the sweet-temperamented Lise Stern. Let us not be lost in obscurity with the once-promising Berlin painter Sabine Lepsius, distracted by the care of others, who wrote bitterly, „Schade um meine Gaben.“

Copy after Selbstbildnis (1885) by Sabine Lepsius, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin

Kollwitz, Käthe. 1988. The diaries and letters of Käthe Kollwitz. Ed. Hans Kollwitz. Trans. Richard and Clara Winston. Northwestern University: Evanston, Illinois.

Shelley, Mary. 2008. Mathilda. Ed. Elizabeth Nitchie. Melville House: Brooklyn, NY.

Woolf, Virginia. [1928] 1963. A room of one’s own. Penguin: Mitcham, Victoria.