Beer, forever bound to agriculture, seems like it should be philosophically opposed to the use of the word "industrial." In an era where "big" is bad to many beer lovers, the mere suggestion of the word can significantly alter perceptions.

Instead of some handcrafted, artisanal product, we suddenly have something wildly opposite. A beer that sounds so ... macro.

But if hop yields are low, and creating new infrastructure is expensive, and drinkers really love a certain kind of hop that has to be grown, is it time to get inventive? Are there processes and products that may create flavorful shortcuts that can continue to produce the hop bombs we've all come to know?

With craft brewers using hops at a per-barrel rate many times greater than big breweries like Anheuser-Busch, it may be worth our time to better understand academic and even industrial advancements that can offer solutions to brewers and not take anything away from the beer we love.

There's a simple challenge here: if craft brewers are going to need millions more pounds of hops to keep up their pace and crank out all those IPAs Americans crave, the process of how they use hops can become more efficient in several ways. Anyone can pile pounds of hops in a kettle, but if there's some strategy and science behind it, maybe there isn't as much of a rush figure out where 21.3 million pounds of hops need to come from to achieve 20 percent market share by 2020.

From a brewing process standpoint, there's lots to consider.

In recent years, pale ales and IPAs have taken on a new flavor of the day, barely focusing on bitterness in lieu of bright aromas and flavors that are akin to the fruit we eat, but in beer form. This shows up in changes in our regular IPA or the recent rise of New England IPAs, aiming for as much a certain flavor as look. The use of hops has shifted in the process, focusing more on late additions, which keep more hop oil in the liquid, and dry hopping, which can provide an array of sensory impressions.

From that point on, however, studies are showing a range of alternatives that might require fewer hops with just as much efficiency. This is most certainly known to brewers, but the research is worth highlighting all the same.

(Of note: this piece by Stan Hieronymus is a great primer on hop characteristics, in addition to the myriad of other work he's done, including this book.)For example, one Oregon State study found that oils from dry hopping were almost fully transferred to a beer after 24 hours, offering a quicker end to the process. It also highlighted the difference between stirring dry hops and leaving them still in the beer, finding that optimal levels of hop characteristics can be achieved within hours, not a "4-12 day industry practice." Modern Times' Jacob McKean highlighted this point in a recent post, noting the success of whirlpool additions commonly used in brewing.

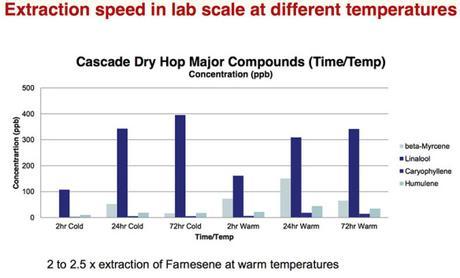

This finding was emphasized at this year's Craft Brewers Conference, where Boulevard Brewing's Steven Pauwels showed in lab testing that after 24 hours, whether at 4 or 20 degrees Celsius, extraction is mostly complete.

In addition, another study by Hopsteiner showed that loosely-packed pellet hops offered nearly 50 percent more extraction efficiency for "a more intense aroma," suggesting that fewer hops could be used for a similar aromatic impact as we smell now. This is particularly important as hop producers add more acreage and seek ways to get better yields.

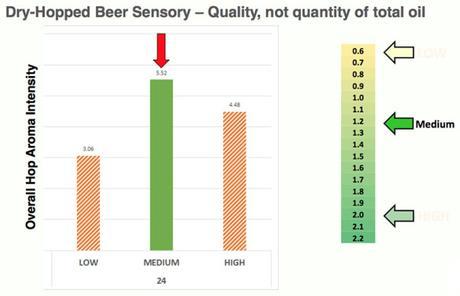

While brewers are keen to these findings, the ultimate goal of highlighting this research is to show how the process can be as important as the ingredients used. Even if hop production is slow to catch up to demand, the way brewers are using hops makes this potential issue a little less daunting. In a presentation made at this year's Craft Brewers Conference, researchers from Oregon State showed the following slide as a way to discuss the topic.

"In this experiment, it was not necessarily the quantity of hop oil that was related to high hop aroma intensity," Dan Vollmer, a Ph. D. candidate explained.

As determined by participating subjects in the study, the "medium" amount of hop oil displayed by Cascade hops delivered better scores than "low" or "high." This finding carried over into additional research in late 2015, leading Vollmer and others to determine that it's not always about the amount of hops you use, but their composition and how you use them.

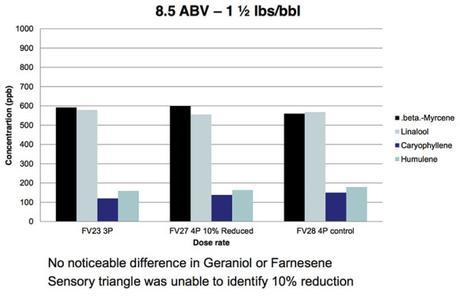

Pauwels also showed a similar result. When doing sensory tests, Boulevard staff found that they could reduce hopping rate by 10 percent at a certain gravity rate (in this case, 4 Plato) and there was no noticeable difference in quality.

He went on to say that depending on usage, tests even showed a 20 percent reduction still gave similar sensory scores. A difference first became obvious once tests went to 30 percent reduction.

"If you think about how much hops you use, how much hops you buy, what impact does it have?" he asked the audience at CBC.

But hop use efficiency isn't the only way to approach how many hops are grown - and ultimately needed for a beer.

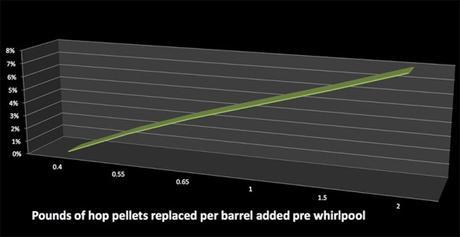

In addition to pellets, Founders Brewing regularly uses liquid hop extract. Alec Mull, vice president of brewery operations, has noted that Devil Dancer, the brewery's Triple IPA, wouldn't be able to be transferred among vessels without using extract because of the volume of physical hops they would make the process rather difficult.

This "industrial" complement to Founders' "traditional" method of hop use is found at all stages of the boiling process for beers, from 10 minute "hop" additions up to the 60 minute bittering charge. Mull pointed out that extract's efficiency takes nothing away from the beer - sensory examinations show brews with hop extract are preferred "100 percent of the time" - but that's not all.

- Hoppy pale ales and session IPA yields 1 to 2 percent more wort

- IPAs yield 3 to 5 percent more wort

- Double IPAs yield up to 8 percent more wort

Hell, there's even a company that is thriving off the creation of hop extracts created to mimic tropical fruit and grapefruit character. Wave of the future or too industrial for our tastes?

However brewers may choose to address their own hopping needs, one thing is for sure: there are ways to get creative when it comes to brewing beer to stay fresh, trendy and at the forefront of beer lovers' minds. Among the many sub-categories of IPA, one particular approach may be most attractive from an educational and sales standpoint.

Bryan Roth

"Don't drink to get drunk. Drink to enjoy life." - Jack Kerouac