When our rafts were bitten by crocodiles or hippos, complications ensued we hadn’t imagined.

We were in Ethiopia making a series of first descents down big rivers that fall off the Abyssinian Plateau: The Omo, Baro, Blue Nile, and the Awash. We called our little expedition Sobek, after the ancient Egyptian crocodile god, hoping the homage would ensure safe passage. But, another challenge reared its head, one unanticipated. When we entered the country, we discovered the customs authorities wanted us to either pay an outrageous duty (150 percent of the cost of the rafts), or prove we exported them after our trips.

They stamped our passports with a notice that conveyed such, and unless we had our passports stamped again with proof of export, we would be assessed and fined, maybe even jailed.

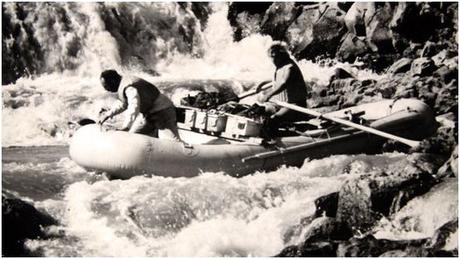

The first descent of the Awash River. Photo by John Kramer

So, when we kept losing our inflatable boats to the jaws of riverine beasts, we needed a plan. It was too expensive to ship shredded rafts back to the U.S. But then Jim Slade, our senior guide, had an ingenious idea. For just a few dollars, we could put the damaged rafts on the train to Djibouti, and have our passports duly stamped as having exported the goods. We didn’t know anyone in what was then The French Territory of the Afars and Issas, so we made up a recipient, Pierre DuPont, and off the torn boats went up the Horn of Africa, never to be heard of again.

The first river we negotiated in Africa was the Awash, starting near Addis Ababa and pouring through severe gorges, over waterfalls, burrowing underground at some points, and emptying into the Danakil Depression, the lowest plug in Africa. Its terminus is a lake with no out outlet, Lake Abbe, which spreads its alkaline waters into Djibouti. Its landscape is so phantasmagoric it was featured in Planet of the Apes. On the final days of our raft descent of the Awash, we fell behind schedule for an arranged air pick-up, so we pulled out at an agricultural station called Gewani. We were just short of Lake Abbe, our expedition left incomplete.

For years I’ve been haunted by these two episodes. What happened to our rafts? What is at the finale of the Awash River.

Finally, I have the chance.

The triggering event is the opening of a direct flight to Djibouti on Qatar Airways. I could fly from LAX (or several other major U.S. cities) non-stop to Doha; wait a couple hours in perhaps the most luxurious airport lounge in the world, and then connect to Djibouti.

I call my friend Scott Siegler, a former studio head who would rather trek into the heart of darkness than date an actress, and he’s on board. So, after a smooth ride to the Arabian Peninsula, and then across it (I’ve decided my favorite hotel in the world is Qatar Airways… always a good night sleep in their flat beds), we make a quick transfer to the Sheraton Hotel, right on the glimmery waters of the Gulf of Aden, and after a freshly-squeezed juice, and a swim in the naturally warm pool, we’re ready to shatter the glass of Western gentility. The timing seems good. The London Telegraph earlier this year named Djibouti “Africa’s Hottest New Travel Destination.”

Still, when I mentioned to friends and family I was heading to Djibouti I got two responses: 1) Where the #!@* is Djibouti; or, 2) Why? Isn’t that the middle of the Hot Zone?

On our second night in the country, we have dinner with the U.S Ambassador, Tom Kelly, at the Café de la Gare, the best restaurant in Djibouti.

The Ambassador is unequivocal: “This is the safest city in Africa.” He points out that Djibouti is the only country in the continent never involved in a war. It is, of course, a strategic location, a sort of backdoor to the universal truths of the region, and as such hosts a lot of military. There is a major U.S base (largest in Africa) with some 4500 Americans. There is a German base; a French base; a Japanese base; Italian; Spanish and others. Seal Team Six is based here. The Chinese are a major economic presence, and are building a new port, new roads; a new railroad; and a major resort on The Red Sea to service Saudis and other high-end tourists.

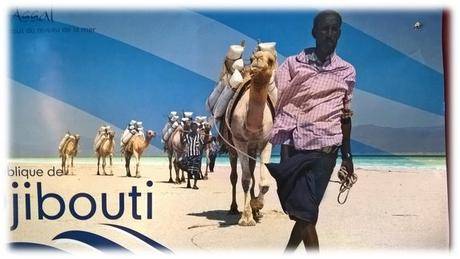

I also meet the Director of Tourism, Mohamed Waiss, who sees Djibouti becoming “The Singapore of Africa,” and naturally touts all its assets, especially its Whale Sharks (best viewing in world), and is introducing the first World Whale Shark Festival. He gives us “I Love Djibouti” gift bags when we leave.

There was a bombing two years ago by an Al-Shabaab woman in a downtown restaurant that killed a Turk. This was, of course, a big deal, but is cited as an exception that might have happened in any European or Asian city. Al-Shabaab is a Somali organization, and not a meaningful presence in Djibouti.

Nonetheless, all the restaurants now have entrance screeners, security guards, and a new police station has been erected a few yards from the restaurant. We take lunch at the modest eatery, and sense no trepidation (except for the salmon, which travels a long way to get here). No American or tourist has ever been harmed by a political/religious group in Djibouti (there was no Arab Spring, and the president is democratically elected.)

Tom Kelly points out that the Djibouti Muslims are fiercely moderate, and proud of it. Djibouti is also a relatively expensive place, so has not attracted the masses of refugees who have flooded elsewhere. The Sheraton has a number of exiled Yemenis, but they receive no discounts, and are of the moneyed class, mostly doctors, lawyers, and successful businessmen, waiting to return when the dust settles. There is a UN refugee camp to the north of the country, but it is far away from the city and attractions, and is apparently well-managed, and it brokers its displaced to willing countries around the world.

The global effort to eradicate the Somali pirates was based here, and Tom Kelly says the united effort has been successful, a rare example of a coalition on a mission that can claim victory. With constant air surveillance and pre-emptive strikes, there has not been a pirate incident in two years.

We walk all about the city, day and night, and drive and explore much of the countryside, and never feel anything less than warm welcomings and open arms.

Djiboutians are very grateful for the U.S presence, and generally embrace Americans, and if possible, would love to marry one and move to Minnesota.

It turns out there are French and Djiboutian firms operating tours, but only one American company, a boutique operation called Rushing Water Adventures, owned by Ken Gradall from Wisconsin. His primary offerings are Whale Shark excursions, paddling in the Gulf of Aden, snorkeling among the remarkable coral reefs (Jacques Cousteau claimed the best in the world), hiking, and trips to the salt lakes. Ken is a former health care worker in Somalia, and speaks fluent Somali, the lingua franca of the Issa, one of the two major clans in Djibouti.

Ken picks us up in his Mitsubishi truck at the airport, and transfers us to the Sheraton, distinctive for its hookah bar, razor wire around the pool, and the stray green parrots. We promptly hit the sack to mitigate the jetlag of a ten-hour time differential. By noon, though, we’re ready to rock. As if to prove the peaceful tone of the city, Ken takes us to lunch at La Chaumiere, the site of the 2013 bombing. The menu is as full and varied as the crowd, with Chinese, Mexican, Italian, Ethiopian and American burgers, but nothing too hot.

The author In the Djibouti Sheraton. Photo by Scott Siegler

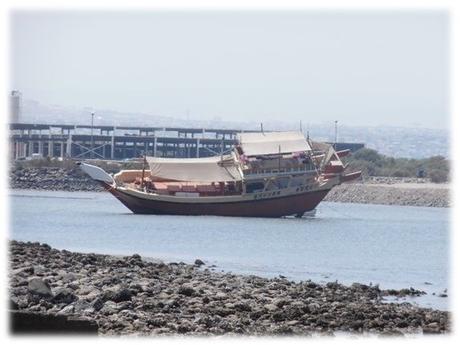

Afterwards, Ken shows us a bit of the town. The main road is lined with graceful old buildings once the haunts of colonial merchants. But the pink and cream facades are now faded, the stuccowork entablatures and rosettes cracked and stained. At a section called the Blue Doors, flamboyant fabrics, slingshots used to airstrike weaver birds, amber necklaces and curved double-edged daggers are hawked. Ken points out the aged mosques with curvaceous ogee arches, and the shiny new foreign-funded versions (including the one where U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry recently spoke). We roll by qat kiosks, a bay full of listing dhows, and the factory that claims the highest per capita consumption of Coke in the world. Djiboutians like to chew qat, a social custom involving a shrub with amphetamine-like qualities, and the preferred mouthwash is a warm Coke.

Dhow Jones. Photo by Scott Siegler

Unlike in the more fundamentalist Muslim countries, where most women are covered in black abayas and hijabs, here the majority dress in vivid rainbow wraps and scarves. “This is the Paris of Africa,” says Ken. “Just look at all this fashion,” and he points to a row of women money changers so vibrant in the cast of their clothes I tell them to keep the change.

Ken parks on a hard beach near the airport, and we launch our New Zealand-made kayaks for an hour paddle out to Turtle Island, floating the seam where the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean meet. Once at the shoreline, we step out of our boats into the shallows and watch as hundreds of blue-spotted stingrays explode from the sand in front of our footsteps and scurry through the clear water. We pass a lone fisherman waist-deep on a sandbar unfurling his net, who recites an impromptu poem for us. In a land with little literacy (less than 1%), storytelling, songs and poetry are vital to keep history, culture and traditions alive, and from fishermen to politicians, skills of oratory carry more weight than any written accords.

We slide back onto our boats and feather towards another island, a Sacred Ibis rookery, and as we get close the sky becomes a high shifting roof of wings. In this stretch we find the turtles, loggerheads, hawksbills and greens, who pop up in front of our bows for a quick look-see, then dive back down into the U.N. protected waters. One of the visual delights of the equatorial desert is twilight, and we paddle back to shore into a dazzling cocktail of orange and red.

The next day we pick up a bag of almond croissants at La Djib House, the neighborhood patisserie, and drive inland, past troops of baboons, the occasional gazelle, and acacias with goats in the top branches, chewing the long, thin thorns contentedly.

Goat Rodeo. Photo by Scott Siegler

About 12 kilometers out we pass the “Who Died Market,” which sells heaps of used clothing. We trundle past dragon blood trees, black lava fields that suck the color from the sun, and bundles of bony firewood for sale by the side of the road. We steer by herds of biscuit-colored goats, scrawny camels with ribs in bold relief, egg-shaped portable huts, and tall, dark nomads wearing sanafils, the signature light cotton skirts knotted at the waist that billow like parachutes in the wind. How do they survive in this slag heap? It looks like they must eat rocks, says Scott.

We pass capsized trucks and Maersk shipping containers in the dry wadis. We stop at the overlook for The Grand Canyon of Punt, where venders offer to sell us geodes, local honey, porcupine quills, sin-black obsidian knives, and plastic water bottles filled with salt.

The Grand Canyon of Punt. Photo by Scott Siegler

We resist the temptations (and the one that plagues me…the desire to hike into any canyon I come across), and we continue the drive down, down into the depths of the Danakil Depression, the Valley of Hell, hottest place on earth. At last it reveals itself, the brilliant white face of Lake Assal, lowest point in Africa, third lowest in the world, the salt sheen spreading like a white ink stain across the water. Beyond, the lake turns into the most seductive Caribbean turquoise color, but nothing lives in this basin. Even the vultures avoid it.

“It is Djiboutiful,” exclaims Ken.

We park, and hike up the Source d’eau chaude, a clear tributary, with hot springs spilling into the waters at fracture points. I drop my Nalgene, filled with ice water, into one of the springs, and it comes out tea. Scott pulls a bag of salted potato chips from his pack, which he says he brought to replenish body sodium leached out by the heat. But he’s bringing coal to Newcastle; we’re in the salt capital of the world.

At the upper end of the canyon there is a clear pool, looking very much like swimming holes in the Grand Canyon, where I once worked as a guide. I didn’t bring a swimsuit, but the water here stirs some ancient urge to shed civilized skin, so I strip and dive in, with Scott and Ken right behind, for a cool hour of soaking. There are hundreds of little fish nibbling at our feet, a free fish spa that would be a pretty peso in Cancun.

At one point a group of Japanese arrive at the edge, and I ask what brings them here. They are from the Japanese base, and that brings my next question….why do the Japanese have a base in Djibouti? Because of the Somali pirates, it turns out. The shipping lanes through the Red Sea and Indian Ocean from Europe to Japan are vital, and so the base exists to help keep the passage safe.

We then crunch across the broad, hyper-white expanse that is the salt-flat of Lake Assal. This is the saltiest body of water in the world, far saltier than the Dead Sea, or the Great Salt Lake, ten times that of the sea.

For centuries the Afar, who claim to be descendants of Noah’s son, Ham, have trekked across the largest salt reserve in the world to load their camels with sacks of the crystalline mineral and then caravan to the highlands for trade, mostly wheat, but also perfumes and spices. It still happens.

A couple of Afars, standing tall and erect on the edge of the lake, try to sell us salt crystals and gazelle skulls coated with salt (a bargain at $10, but how to get home?). And there is a memorial plaque to Bernard Borrel, a French judge found burned to death in a ravine near here in 1995, a casualty perhaps of the spaces the empire left behind.

While walking the shoreline (it is 110 degrees in the shade, but there is no shade) we come across a group of large men, Dwayne Johnson-sized. They share they are NCIS-Djibouti, stationed at the U.S. base, taking a day trip before heading back for Meatball Marinara sandwiches at the base Subway, the highest grossing of the franchise in the world, they say. That pricks our appetite, and we begin to head back to the car so we can make dinner with the U.S. Ambassador. As we climb out of the lake basin, Ken stops the car and has us get out. There is a diagonal crack in the road, like a scar on the face of the landscape, and it runs to the horizon in both directions. We straddle the jagged fissure, and Ken says that we have a foot each on the two great tectonic plates, the Arabian and African, which are slowly splitting the continent, similar to how Madagascar cut away from the homeland 150 million years ago.

I had hoped to make it to Lake Abbe, the terminus of the Awash River on the Ethiopian border, to conclude the trip I had started some 42 years ago. But Ken disabuses me of the idea with our short stay… it is a two-day trip out and back to Abbe, and we are in-country for just four. But as I look at the map, and back down to the lowest point in Africa, and the rift that created this sink, I realize that this valley must have once exceeded its frame. The waters of the Awash must have, in an earlier epoch, run further downwards, as all rivers do, until it reached the bottom. That would be Lake Assal. No water runs between the two lakes…it evaporates. But the climate was once milder, the region wetter, so in an earlier geological time, this was the end of the line. In some fashion, I could say, I at last finished my journey down the Awash River.

The next day, under an oyster blue sky, we set out to Arta Plage, the famous beach where the whale sharks congregate each winter to feed in the rich meeting of the waters of Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. I’ve dived with the whale sharks in Cancun, but Ken says that experience is nothing compared to the behemothic banquet found here each season.

But, we’re early, by just a few days (the season is November to February), and so instead go snorkeling along the most colorful reef system I have ever seen. I’ve dived in many places, from the Caribbean to the Galapagos to Bali to the Andaman Islands, but I am not prepared for this. I have been colorblind my whole life, but now, halleluiah, I can see. It practically pulses with HD colors; it pops like a Cirque du Soleil, spins like a candy pinwheel, or at least how I always imagined a pinwheel of bright colors looks like. And that’s just the coral…there are butterfly fish, angel fish, parrot fish, damsel fish, duke fish, surgeon fish, and a hundred and one others I can’t identify.

Across the water from this beach we can look up to bosky headlands, mile-high volcanic mountains that look, in their middle reaches, as though scumbled by a painters’ brush, though the summit lines are sharp, scraping the blue welkin like an etching knife. I almost expect the sky to bleed.

We make it back to town in time for dinner at Time Out, an Italian/Ethiopian restaurant on the main square, owned by Vittorio Gulla, a friend of a friend who lives in Addis. Vitto says he moved to Djibouti from Addis only recently because he finds the coastal environmental friendlier. It’s a long wait between ordering and serving–the gears here turn more slowly than at home–but when the plates arrive Scott scoops into some injera and wat, while I indulge in pasta primavera with a St. George beer. We pay in cash, as few eateries or shops in Djibouti take credit cards, and then head back to the Sheraton, where an Afar wedding is unfolding, in shimmering costumes and a traditional type of dance, called jenile, colorful as a Djiboutian coral reef.

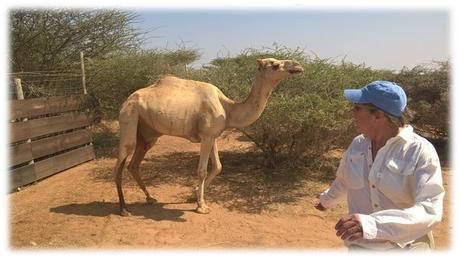

The next day is our final. We had hoped to take the ferry across the Bab-el-Mandeb (Arabic for “gate of tears”) strait to the old slave-trading settlement of Tadjoura to check out an eco-lodge, but we miss the boat. So, instead we drive a short ways out of town to the Decan Wildlife Reserve, an interactive park where you can walk among the animals (at least the herbivores; the predators are fenced). We step among zebra, Arabian Oryx, porcupines, dik-diks, giant tortoises, gazelles, ostrich, murders of crows; and, we get close enough to cheetahs, caracals, lions and rogue camels to speed the blood.

Scott Siegler being chased by a rogue camel

On the last afternoon, I ask Ken to drive me to the Train Station where we once shipped our bitten rafts. It’s closed now, the rail run to Ethiopia a cartouche of memory. The Chinese are building a new rail line scheduled to open soon, leaving the old station to slowly collapse and return to dust.

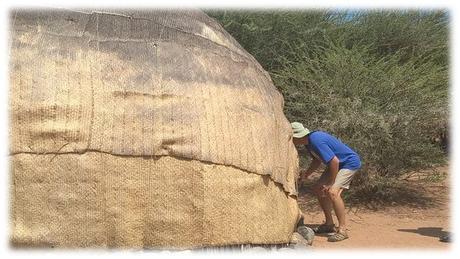

I make my way inside where a guard stops me and says it is unsafe. I ask if he might know where some old inflatable rafts might be stored. He doesn’t know what I’m talking about, and shoos me out. I walk around the outside…it’s a wide building with narrow, lancet windows… and there in the back is a rounded Afar hut held together with an assortment of fabrics, like patches on a leaking ship. Inside is a bed, a fire pit, a palm-leaf mat, and a block of salt, meant to ward off djinns. But as I look closely at the dark material draping the acacia skeleton of the structure I think I can make out a faded logo: Sobek.

There is only one U.S.-based travel company offering customized tours to Djibouti: MTSobek

Contact Justin Huff at [email protected] for details.

If you’d like to paddle and swim with the Whale Sharks, or take an adventure organized and run by a local outfitter, contact Rushing Waters Adventures, and owner Ken Gradall at [email protected] or visit: www.kayakdjibouti.com