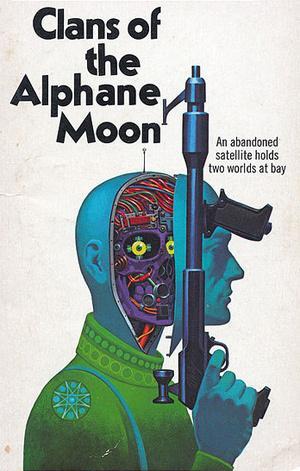

Clans of the Alphane moon, by Philip K. Dick

Any book that features a telepathic yellow Ganymedean slime mold as a major character can’t be all bad, even if it does show a frankly creepy interest in its female characters’ breasts.

Philip K. Dick has won a certain critical acclaim in recent years, with readers who wouldn’t normally look at SF being aware at the very least of his most acclaimed titles. Dick though was prolific. Sure, there was Ubik and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (best title ever?) and the other big hitters, but there was also a ton of pulp SF.

Our Friends from Frolix 8 (another great title). The World Jones Made. A Maze of Death. Clans of the Alphane Moon. None of them first rank Dick, certainly none of them literary Dick, but each of them a solid piece of classic SF.

Chuck Rittersdorf is in the process of being divorced by his wife, Mary, a famed marriage counselor. Mary’s frustration with his lack of ambition has been building for years, and she’s enacting her revenge by taking so much of his money in the settlement that he’ll be forced to go for a higher paid job just so he can pay her alimony.

Gleefully she placed the last sweater in the suitcase, closed it, and with a rapid turn of her fingers, locked it tight. Poor Chuck, she said to herself, you don’t stand a chance, once I get you into court. You’ll never know what hit you; you’ll be paying out for the rest of your life. As long as you live, darling, you’ll never really be free of me; it’ll always cost you something. She began, with care, to fold her many dresses, packing them into the large trunk with the special hangers. It will cost you, she said to herself, more than you can afford to pay.

Mary is, unfortunately, one of the most sexist depictions of a female character I’ve read in years. There’s a lot to like in this book, some great ideas and a lot of nicely done comedy, but its treatment of women is actively unpleasant. Every female character description includes noting what her breasts look like, it’s dressed up in terms of some future fashion involving nipple dilation but it’s blatantly just something Dick is fixated on. The only woman to have any agency as a character is Mary, and she’s a self-deluding shrew. I don’t defend any of this. If you read this book you read it despite its monumental sexism. I don’t think that means it shouldn’t be read, because there are a lot of great ideas here, you just have to wade through some crap to get to them.

Chuck, the hapless husband, writes dialog for CIA propaganda robots. He’s good at it, with a keen eye for comedy that gets the targets listening. His wife wants him to work as a scriptwriter for famous comedian Bunny Hentman (real name Lionsblood Regal, he had to tone it down, “who goes into show biz calling himself Lionsblood Regal?”). Bunny would pay a lot more than the CIA, but Chuck enjoys his work and likes being a public servant. If he’s going to meet his alimony though he’ll need more than a government paycheck.

Meanwhile, in the Centauri system, a psychiatric colony abandoned 25 years ago after a disastrous war has evolved its own unique culture. Now Mary has been appointed as one of the crew sent to reestablish contact, to provide aid to the profoundly mentally ill colonists, and of course to take it back under Earth control. They claim it’s a mission of mercy, but it’s colonialism plain and simple.

In the colony meanwhile, they’ve adapted and without anyone there to tell them they’re broken they’ve created a functional society. They’ve built cities, with the population of each sharing a common mental illness.

The Pares live in Adolfville, where they develop new strategies and technologies to protect themselves against their many presumed enemies. The Manses live in Da Vinci Heights, making new breakthroughs in art and science in a frenzy of enthusiasm, each of which they rapidly bore of. The Skitzes have Joan d’Arc, where they have ecstatic visions of a greater reality and act as poets and priests to the others. The Heebs have Ghanditown, a disorganised hovel where they eschew ambition and materiality and slip slowly into catatonia. There’s the Polys, from Hamlet Hamlet, who remain childlike for life, imaginative dreamers but impractical. The Ob-Coms run the administration, making sure everything works. Finally the Deps dwell in “endless dark gloom” in Cotton Mathers Estates.

The colonists have a council with a representative from each city, and the opening scene of the book where Gabriel Baines, the Pare representative, attends the council meeting is brilliantly funny. Gabriel doesn’t just walk in of course, he first sends in a robot double to check for traps. Once inside he changes seat, argues with the Manse representative, is frustrated by the Heeb who spends much of the time sweeping the floor, and waits impatiently for the Skitz who finally shows up floating in through the window.

They’re meeting because Manse telescopes have picked up the ship from Earth, and they’re wondering how to defend themselves. The Earth ship says it’s come to help them, but as one of its crew notes: “Those people in Adolfville may be legally and clinically insane, but they’re not stupid”.

In large part this is a satire on the artificial boundaries between sanity and insanity. The colonists may not have the greatest society in history, but the one back on Earth doesn’t look so hot either. When someone observes “Frankly, we feel there’s nothing more potentially explosive than a society in which psychotics dominate, define the values, control the means of communication.” they’re talking about the colonists, but as reader you can’t help feeling Dick’s talking about his contemporary America.

There’s some lovely irony as the people on the ship, the sane ones, justify to themselves what’s essentially an act of unprovoked aggression on their part. Here Mary briefs the rest of the crew:

Our presence here will accelerate the hallucinating tendency; we have to face that and be prepared. And the hallucination will take the form of seeing us as elements of dire menace; we, our ship, will literally be viewed—I don’t mean interpreted, I mean actually perceived—as threatening. What they undoubtedly will see in us is an invading spearhead that intends to overthrow their society, make it a satellite of our own.”

“But that’s true. We intend to take the leadership out of their hands, place them back where they were twenty-five years ago. Patients in enforced hospitalization circumstances—in other words, captivity.”

It was a good point. But not quite good enough. She said, “There is a distinction you’re not making; it’s a slender one, but vital. We will be attempting therapy of these people, trying to put them actually in the position which, by accident, they now improperly hold. If our program is successful they will govern themselves, as legitimate settlers on this moon, eventually. First a few, then more and more of them. This is not a form of captivity—even if they imagine it is. The moment any person on this moon is free of psychosis, is capable of viewing reality without the distortion of projection—”

“Do you think it’ll be possible to persuade these people voluntarily to resume their hospitalized status?”

“No,” Mary said. “We’ll have to bring force to bear on them; with the possible exception of a few Heebs we’re going to have to take out commitment papers for an entire planet.” She corrected herself, “Or rather moon.”

I’ve barely touched here on the plot. Chuck tries to kill himself, but is interrupted by his next door neighbour, a telepathic slime mold from Ganymede (“I had planned to borrow a cup of yogurt culture from you, but in view of your preoccupation it seems an insulting request.”) With the Ganymedean as unlikely mentor he decides instead to remote control a propaganda robot on Mary’s ship to murder her, figuring he can blame it on the colonists. Can the colonists defeat the Earth ship? Can Chuck and Mary reconcile their differences? Are the CIA right that Bunny Hentman is really a spy for blind alien insects? If you want to know the answers, you’ll have to read it to find out.

I’ll end with one final quote. I’ve chosen this one because it illustrates why despite the appalling sexism I still rather like this book. Here the council is voting on a plan that might just save them all:

When the total vote had been verified everyone but Dino Watters, the miserable Dep, turned out to have declared in the affirmative.

“What was wrong with you?” Gabriel Baines asked the Dep curiously.

In his hollow, despairing voice the Dep answered, “I think it’s hopeless. The Terran warships are too close. The Manses’ shield just can’t last that long. Or else we won’t be able to contact Hentman’s ship. Something will go wrong, and then the Terrans will decimate us.” He added, “And in addition I’ve been having stomach pains ever since we originally convened; I think I’ve got cancer.”

Other reviews

None on the blogosphere that I know of, though I’m sure there are some. There’s a great piece here in the Guardian though by writer Sandra Newman which uses Clans as an example of how some old-school SF could be at the same time wildly inventive and wildly offensive, and how perhaps both qualities arose out of the genre’s lack of literary credibility and so the lack of any need to pander to any expectations of good taste or convention. It’s a good article, and even if you never read the book I think her argument is still worth considering.

Filed under: Dick, Philip K, Science Fiction Tagged: Philip K Dick