The Invention of Morel, by Adolfo Bioy Casares and translated by Ruth Simms

The Invention of Morel comes with an endorsement by Borges stating simply that “To classify it as perfect is neither an imprecision nor a hyperbole.” I disagree.

An unnamed fugitive makes his home on an uninhabited pacific island. He plans to live out his remaining years there safe from discovery and the imprisonment that would inevitably follow. We do not know of what crime he is accused but we know it must be serious.

The island has a handful of empty buildings but its inaccessibility makes it a safe refuge. Or so it seemed until without warning a group of apparent holidaymakers appear among the buildings. They seem utterly ignorant of the fugitive’s presence. Are they ghosts? Is he? Is this some malevolent prank on their part aimed at his capture? Or is the truth much stranger?

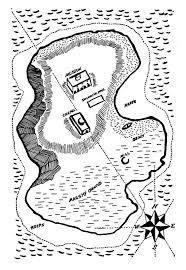

The book comes with some rather charming illustrations. Here’s a map of the island showing the various structures on it:

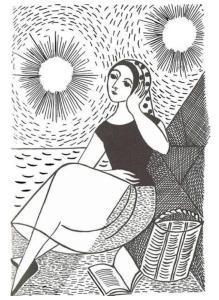

And here is a mysterious sunbathing woman named Faustine with whom the fugitive falls furtively in love:

At first he daren’t approach her, uncertain both as to the group’s intent and her likely reaction. When he does he finds to his dismay that she doesn’t acknowledge him. It’s as if he were invisible, inaudible. He tries to make tribute to her by planting a floral garden where she sunbathes each day:

When I made this garden, I felt like a magician because the finished work had no connection with the precise movements that produced it. My magic depended on this: I had to concentrate on each part, on the difficult task of planting each flower and aligning it with the preceding one. As I worked, the garden appeared to be either a disorderly agglomeration of flowers or a woman.

That quote seems as obvious a metaphor for the process of writing a novel as one could hope for. Casares’ book was well received; the garden isn’t even glanced at. A male companion, Morel, visits the woman and walks over the flowers as if they weren’t there.

The problem is that it’s evident very early on that the holidaymakers are genuinely oblivious to the narrator. Unfortunately, the plot requires that he doesn’t realize this which means that he wanders about coming up with bizarre hypotheses for why everyone pretends not to see him despite it being perfectly apparent that they can’t (and despite other plainly outré events such as seeing two suns in the sky). I worked out what was going on pretty quickly (it’s not hard if you’ve read any pulp SF) but the narrator struggles even after Morel spends four pages (four!) in outright exposition setting out precisely what’s happening.

This next quote comes after the narrator has spent those four pages listening to Morel explain in detail the nature of his invention, after which everyone seems to vanish without trace:

There was no noise, there was almost no light. Had they all gone to bed? Or were they lying in wait to capture me?

Really? Four pages of exposition and he still doesn’t get it? The narrator doesn’t understand because the plot requires him not to. It’s clumsy, to be kind.

Invention is not generally seen as a genre novel. I’m not quite sure why that is since it’s actually a pretty straightforward SF tale. It deals in issues of mortality, love and how we ascribe meaning to our lives but there’s no rule that genre can’t address big issues.

It is well written and perhaps that’s why it’s won so many fans. I loved for example this quote which comes when the narrator is considering just declaring his passion to Faustine without further attempt to win her by garden gift or subtle wooing:

We are suspicious of a stranger who tells us his life story, who tells us spontaneously that he has been captured, sentenced to life imprisonment, and that we are his reason for living. We are afraid that he is merely tricking us into buying a fountain pen or a bottle with a miniature sailing vessel inside.

Casares is of course quite right. I think most of us have had the experience of some seemingly friendly stranger on a holiday turning out to have a timeshare to sell or a hard-luck story tucked away ready to bring out once trust is won. On the other hand the quote’s charm was lessened for me by the fact that there seemed no reason that the narrator shouldn’t already have realised that Faustine simply wouldn’t hear him if he poured his heart out.

By the close the narrator comes to understand what’s going on and the implications for his love. For me, the final few pages are the best in the book as the narrator responds to his situation and creates meaning from it. His response has a certain questionable beauty which I can’t explain or discuss without spoiling this utterly for future readers. It’s just a shame that he has to understand so little along the way and ignore so many evident incongruities in order to make it all work.

It’s rare I write a review this negative and all the more so when as here the book is well written. I may well read more Casares just because he plainly can write. For me though Invention was contrived with character and behavior painfully twisted to serve the demands of unrelenting plot and situation. I didn’t think the payoff worth the journey.

Other reviews (and a note on the translation)

Several, and mostly glowing. Kaggsy describes this as “perfect” and a “five-star read” here; Gautambhatia pays considerable tribute to the book here in a review I’d describe as itself being perfect and a five-star read, not least for his clearly marked spoiler section; other reviews of interest (though more ambivalent ones to my eye) are from Grant of 1st Reading’s blog here and from Jacqui of Jacqui Wine’s journal here.

Finally, there’s a good piece here on the problems of the translation. Unfortunately it appears it’s pretty poor with plenty of changes, needless tidying and outright omissions. It looks like Casares meant it to be even more obvious to the reader what’s going on than it already was to me. I think that might have helped, because it would have brought out the intentional artificiality of the narrator’s obtuseness by making everything all the more apparent. It’s a shame. I may not have liked the book but Casares deserved better.

Filed under: Casares, Adolfo Bioy, Spanish Literature Tagged: Adolfo Bioy Casares