A French court decreed that a teenaged boy was entitled to compensation for having been born. Medics had failed to detect conditions resulting in severe birth defects, leaving the child deaf, mentally challenged, and nearly blind. Had his parents known to expect this, they’d have aborted. Would that have been better for him?

Well, there might have followed another, normal pregnancy, and presumably you would rather be normal. But that would have been a different person, doing no good for the first kid, who would never have existed.

And isn’t existing better than not existing? People generally feel so — holding onto existence with fierce tenacity, even if professing to expect a heavenly afterlife. And even if having lives full of pain and suffering.

Maintaining existence in such circumstances is a choice, and some people do opt out. Yet not only are suicides a small minority among suffering people, but suicidal impulses tend to be transient even for ones who attempt it — most who fail don’t try again. This too illustrates the power of the preference for existence over nonexistence.

Something I read long ago really stuck with me. In surveys, greater than average happiness and life satisfaction were reported by people confined to iron lungs. How could that be? Maybe such people were more keenly mindful of life’s precariousness, with its difficulty making them value all the more what they did have.

You yourself might imagine that, given certain circumstances of misery and suffering, your life might not be worth living. Like in an iron lung. But you may — likely would — think differently if you were actually in the situation. That’s why we invented iron lungs, positing that life in one is better than no life at all — thus worth living.

Viktor Frankl’s message in Man’s Search for Meaning was similar. There, the suffering addressed was that in a Nazi concentration camp. Some inmates did succumb to despair; but others could find meaning for their lives even in such awful circumstances.

Philosopher Peter Heinegg, in Better than Both: The Case for Pessimism (a counterpoint to my own book), said that better than life or death is never being born at all. (Though he himself seemed to greatly enjoy living.) And the great moral philosopher Peter Singer has suggested euthanizing a child born with likelihood of a miserable existence. With the only cavil being the trauma for the parents. I’ve always found Singer’s work a reductio ad absurdum of moralism.

These notions return us to the French teen’s case, and the idea that his very existence does him compensable injury. Does he indeed wish he’d never been born? Or — is he lucky the pregnancy problem went undetected, thus averting abortion?

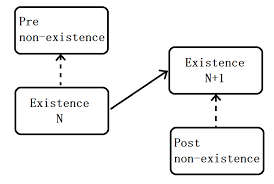

So, what is it about existence per se that makes it a positive thing? It’s hard to conceptualize because the contrary condition — nonexistence — is impossible to truly model in one’s mind. Asking what nonexistence would feel like is nonsensical.

Existence being indeed the sine qua non for everything. Even the universe. Why it does exist, as opposed to there being nothing, is a devilish problem, but it would be moot if the universe were nonexistent.

Whether any life is worth living is a question of value, and what value means in such a context is a fraught question. Value to who being one aspect. The individual in question, mainly, but if that individual were nonexistent (as with the universe) the matter becomes moot.

So, to restate the point, existence is the foundation for everything that could come under the rubric of value. While nonexistence excludes any ideation of value. That makes the phrase “life not worth living” an absurdity. Only in the context of existence, as opposed to nonexistence, can one speak of anything being worth anything.

Advertisement