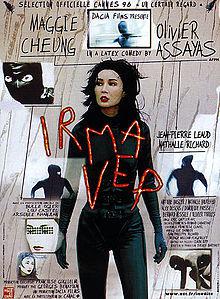

Irma Vep is the third Olivier Assayas film I've seen, the other two being Summer Hours and Carlos. This 1996 feature contains the roots of both, the former's elegant respect for French art history and the latter's deconstructive, post-New Wave wit. A film about a film production starring Jean-Pierre Léaud, Irma Vep instantly recalls Day for Night, but as Assayas voices and visualizes a sense of dissatisfaction with French cinema, the film becomes something else. Eric Gautier's gritty, 16mm cinematography and sophisticated camera movements combine New Wave spontaneity (the film was shot in three weeks) with formal know-how to be both behind-the-scenes docudrama and rich cinematic fantasy.

Irma Vep is the third Olivier Assayas film I've seen, the other two being Summer Hours and Carlos. This 1996 feature contains the roots of both, the former's elegant respect for French art history and the latter's deconstructive, post-New Wave wit. A film about a film production starring Jean-Pierre Léaud, Irma Vep instantly recalls Day for Night, but as Assayas voices and visualizes a sense of dissatisfaction with French cinema, the film becomes something else. Eric Gautier's gritty, 16mm cinematography and sophisticated camera movements combine New Wave spontaneity (the film was shot in three weeks) with formal know-how to be both behind-the-scenes docudrama and rich cinematic fantasy.That the production in question is an adaptation of Louis Feuillade's 1915 serial Les Vampires only complicates Assayas' thematic intent. The characters working on this French film set all talk of American films, some disapprovingly, others with an eagerness to see their own national cinema reflect Hollywood's crowd-pleasing scale. Assayas "remakes" Feuillade's film to remind everyone that France invented the action epic, and that they didn't need insane budgets and special effects to do so. Yet the fact that someone would remake it speaks to a lack of original ideas for contemporary French directors, and that's leaving out how little of France seems to make its way into this production.

This is most evident in the casting of the titular lead role. Rather than use a native French actress, director René Vidal (Léaud) selects Maggie Cheung (Maggie, well, Cheung) after seeing her in some Hong Kong films. To demonstrate why he cast her, Vidal plays a clip of Cheung in Johnnie To's The Heroic Trio, seen on a cheap video with forced subtitles that include Chinese characters with bad, scarcely legible translations. (This looks achingly familiar to anyone who has watched a To film made in the late '80s and early '90s.) Vidal, who will later be derided as a director who represents stuffy, insular French film, is already looking to the styles of other countries to aid his own movie, and his casting suggests a lack of faith in native talent.

It only gets more complicated and un-French from there. In designing an update on Musidora's catsuit in the original serial, the fashion designers head to a sex shop and grab a latex suit. To get the right look and feel for the catsuit, however, the designer, Zoé (Nathalie Richard) does not look at stills from Feuillade but rather a magazine photo of Michelle Pfeiffer's Catwoman from Batman Returns. Zoé later confides in Cheung that she hated Tim Burton's movie and its ludicrously outsized style, but she's still looking to the American film for inspiration. This is even more ironic as Assayas subtly hints that Burton, whether he realized it or not, copped Catwoman's get-up from Musidora, so the French are now chasing after people who technically already copied them.

When it comes time to shoot, the production is a disaster. Vidal and the crew go over dailies that lack any and all tension, atmosphere or eroticism. The dailies, like the silents they copy, play in black-and-white and without any soundtrack other than the idle cough of one of the watching crew. When the lights come up, Vidal is a nervous wreck, having only now realized, with money and people secured, that he is wasting his time. French film really is in a rut, it seems. But then, Cheung, who moves so stiffly and uncomfortably in the latex suit during shooting, returns back to her hotel room after hanging out with Zoé, puts on a Sonic Youth record, dons the catsuit and goes out for a prowl. Suddenly, Cheung moves with ease, and she even lifts the necklace of an American woman who waits nude for a lover who won't come over.

This is the only outright fantastical moment of the film (well, other than the ending), but it marks a shift away from a movie about the making of a movie into one about the possibilities of cinema. With the Les Vampires production itself more or less halted with Vidal's nervous breakdown, Assayas can probe deeper into the characters and how they relate to each other through blurs in diegetic realities. Both Vidal and Zoé have crushes on Cheung, but they project onto her in such a way that they seem to love Maggie Cheung, the lead character, and not Maggie Cheung, the actress. Zoé dresses Cheung up in latex for the movie, but that catsuit also becomes an erotic fantasy for her, and the designer even imagines Cheung having expressed a deep love of the uncomfortable thing, creating the invented possibility of the woman wearing it around her in private.

Cheung herself, working with people with whom she can only communicate via her and their second language (English), plays in her own fish-out-of-water tale that complicates her involvement in the film. Indeed, one person even voices a vicious complaint about the casting of a foreigner to play a character who symbolizes the Paris underground, though Assayas clarifies the limits of his own argument for the vitality and independence of French cinema by casting this man's rants as racist and myopic. Assayas may want to stake a renewed place for French film, but he also knows that an outside presence can offer new perspectives, and he uses Cheung to find alternate routes through both the fake remake and the actual movie being watched that lead to new ideas for national cinema.

But for all this ambition, there are many playful, even hilarious, moments found in the film. When Zoé tries on the latex mask she's designed for Cheung's Irma, she, being French, takes one last puff on a cigarette before this three-second break in being able to inhale. She gets the thing on and sighs, sending smoke pouring out of the mask's eye and mouth holes. When Cheung morphs into a cat burglar and takes the American's necklace, she also eavesdrops on the woman's angry phone call with the lover, complaining that she's done everything to kill time, even seeing every movie playing in town. This includes the new Steven Seagal picture, which the woman singles out for perhaps the greatest offense of the entire jilting.

The funniest, and most incisive, scene, though, involves an on-set interview Cheung gives to a French reporter. The scene, opening on the lens taking the place of the camera being used to film this for TV, starts with Cheung answering a question about working with Jackie Chan, hinting at a bias on the interviewer's part soon made explicit. This young man continues to ask about her involvement in Hong Kong action films, his obvious enthusiasm for them undeterred by Cheung admitting she finds them "too masculine." No sooner does she say these words than the man cuts her off, raves more about John Woo movies and even makes finger pistols to act out his favorite shots. He goes on to disparage Vidal's work, calling it self-indulgent crap made only for the intelligentsia, stereotypical French cinema personified. Cheung tries to argue for the need for different forms of filmic expression, but the reporter won't listen. The scene is a hilarious, and passionate, form of film criticism, with Cheung finally arguing in favor of a blend of commercial and art filmmaking. But it also makes me wonder if this Yank wannabe is the French version of a snob. In America, the snob rails against the most visible forms of national entertainment and champions the work of lesser-knowns and those outside the country. If French film is typified by navel-gazing auteurism, is the discerning aesthete the one who pines for Jean-Claude Van Damme movies?

"Cinema is not magic," reads a scrawl in a political film shown at Zoé's pad. "It is a technique and a science." Irma Vep agrees with that assessment, but it also shows how technique and science engender magic in an audience. Cheung's kind, gentle rejection of Zoé is followed by camerawork so gorgeous yet tragic that Assayas visualizes the shattering of that cinematic spell and the devastation of reality. And the final scene, in which the old dailies are replayed but rent apart by experimental etches and white noise, breaks the entire movie's magic, illustrating technique's power to create through its equal ability to destroy. This sequence heavily references Isidore Isou's experimental film Venom and Eternity, yet like the rest of the film, this look to the past makes the case for the future of French cinema. Assayas demolishes the entire frame, but in his expression of dissatisfaction with his country's filmic output there is also a clear belief that it can still be the greatest cinema in the world, as it so often has been. Had other French directors followed Assayas' lead, he might have set off a New New Wave.