Once I'd finished Tyler Cowen's The Great Stagnation I decided to take a look at his next book:

Tyler Cowen. Average Is Over: Powering America Beyond the Age of the Great Stagnation. Dutton (2013).

As the title indicates, the book looks toward the future, something I'm interested in these days. So I poked around, found things of interest, and made some notes.

I found Cowen's remarks on Freestyle chess most interesting and have some notes on that in the next section. I skip over several chapters to arrive at his treatment of science in Chapter 11, where I spend an inordinate amount of time quarreling with his guesstimates about the capabilities of artificial intelligence. Then I move to the last chapter, "A New Social Contract?". That brings us to the heart of this post.

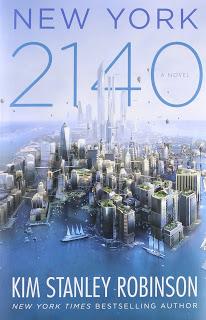

For the world Cowen sketches in that last chapter seems roughly compatible with the one Kim Stanley Robinson created in New York 2140, which, as far as I can tell, takes place somewhat beyond the (unspecified) time horizon Cowen has in Average Is Over. I dig out an unpublished essay of Cowen's, "Is a Novel a Model?", and use it to situate the two books in the same ontological register. I argue, in effect, that New York 2140 takes more or less the world Cowen projects in Average, pushes it through climate change, cranks some parameters up to eleven, and concludes with a replay of the 2008 financial crisis, albeit to a rather different conclusion.

Then we arrive where I'm really going, the "Heart of Deepest Africa", Kisangani, a commercial city in the center of the Congo Basin. What will life be like in Kisangani in 2150, a decade after the institutional upheaval that ends Robinson's book? I don't answer the question, I merely pose it.

Pour yourself some scotch, coffee, kombucha, whatever's your pleasure. This is going to be a long one.

Cowen introduces Freestyle chess in Chapter 5, "Our Freestyle Future". Freestyle chess is played by teams that include one or more humans and one or more computers (p. 78):

A series of Freestyle tournaments was held staring in 2005. In the first tournament, grandmasters played, but the winning trophy was taken by ZackS. In a final round, ZackS defeated Russian grandmaster Vladimir Dobrov and his very well rated (2,600+) colleague, who of course worked together with the programs. Who was ZackZ? Two guys from New Hampshire, Steven Cramton and Zackary Stephen, then rated at the relatively low levels of 1,685 and 1,395, respectively. Those ratings would not make them formidable local club players, much less regional champions. But they were the best when it came to aggregating the inputs from different computers. In addition to some formidable hardware, they used the chess software engines Fritz, Shredder, Junior, and Chess Tiger.

Cowen later notes (p. 81):

The top games of Freestyle chess probably are the greatest heights chess has reached, though who actually is to judge? The human-machine pair is better than any human - or any machine - can readily evaluate. No search engine will recognize the paired efforts as being the best available, because the paired strategies are deeper than what the machine alone can properly evaluate.

And that was before AlphaZero entered the picture [1].

Cowen then uses Freestyle chess as his model for man-machine collaboration in the future of work. That's a reasonable thing to do. But I have a caveat.

Most task environments are ill-defined and open-ended in a way that chess is not. From a purely abstract point of view, and given an appropriate rule for converting a stalemate into a draw, chess, like the much simpler tic-tac-toe, is a finite game. That is, there are only a finite number of games possible. So, in point of abstract theory, one could list all possible games in the tree and label each path according to how it ends (win, lose, or draw). Then to play you simply follow only paths that can lead to a win or, if forced, to a draw. However the number of possible games is so large that this is not a feasible way to play the game, not even for the largest and fastest of computers.

However, while computers have been able to beat any human at chess for over two decades they still lag behind six year olds in language understanding, though they can be deceptive in "conversation". Linguistic behavior isn't the crisply delimited task world that chess is and so presents quite different challenges to computational mastery. The so-called "common sense" problem is pretty much where it was dropped with the eclipse of symbolic-AI over a quarter of a century ago. Cowen isn't mindful of this issue, which bleeds into many task domains, and so tends to over-generalize from Freestyle chess. I don't think that over-generalization does much harm to is overall argument, but it does lead him to overplay his hand when he discusses the future of science.

So let's skip to Chapter 11, "The End of Average Science" (p. 206):

For at least three reasons, a lot of science will become harder to understand:

- In some (not all) scientific areas, problems are becoming more complex and unsusceptible to simple, intuitive, big breakthroughs.

- The individual scientific contribution is becoming more specialized, a trend that has been running for centuries and is unlikely to stop.

- One day soon, intelligent machines will become formidable researchers in their own right.

On the first, it seems to me we made a good start on that early in the 20th century and relativity and even more so with quantum mechanics. Still, Cowen cites mathematical proofs that run on for pages and pages and take years for other mathematicians to verify. Are we in for more of that? Maybe yes, maybe no, who knows? And maybe, as I've been suggesting in connection with cognitive ranks theory [2], fundamentally new scientific languages will precipitate out of the chaos and return us to a regime where intuition can lead to breakthroughs. In the past pre-Copernican astronomy had a horrendously complex model of the relations between the earth, sun, moon, and other plants, with epicycles upon cycles. But then Copernicus suggests we center the model on the sun and Kepler abandoned circular orbits for elliptical ones and the model became at once simpler (fewer parts), but also more sophisticated. This more sophisticated model was so sensitive that observed anomalies in the orbit of Uranus led to the discovery of Neptune.

I agree that specialization is here to stay (#2). As for machines becoming formidable researchers (#3), color me bemused and skeptical. Let's skip ahead (217-218):

Most current scientific research looks like "human directing computer to aid human doing research," but we will move closer to "human feeding computer to do its own research" and "human interpreting the research of the computer." The computer will become more central to the actual work, even to the design of the research program, and the human will become the handmaiden rather than the driver of progress.

An intelligent machine might come up with a new theory of cosmology, and perhaps no human will be able to understand or articulate that theory. Maybe it will refer to non-visualizable dimensions of space or nonintuitive understandings of time. The machine will tell us that the theory makes good predictions, and if nothing else we will be able to use one genius machine to check the predictions of the theory from another genius machine. Still, we, as humans, won't have a good grasp on what the theory means and even the best scientists will grasp only part of what the genius machine has done.

I sorta' maybe kinda' agree with the first paragraph, but stop at the point that it implies that second paragraph.

First, I've got a philosophical problem. Here we have an expert in cosmology, the best humankind has to offer. She's examining this impossible-to-understand theory and the verification of predictions offered by a genius machine. How is she to tell whether she's examining valid work or high-falutin' nonsense? If she can't understand what they're doing, why should she believe the two genius machines? I'm sure this one can be argued, but I don't want to attempt it here and now. So let's just set it aside.

Let's instead consider a weaker claim, simply that we'll have genius machines whose capacity to propose theories, in cosmology, evolutionary biology, post-quantum mechanics, whatever, is as good as any human. How likely is that? I don't know, but I want to see an argument, and I can't see that Cowen has offered one. Nor can I see what he'd offer beyond, "computers are getting smarter and smarter by the day".

In the opening chapter Cowen mentions Ray Kurzweil, one of the prime proponents of the inevitability of computational superintelligence that surpasses human intelligence. He neither endorses nor denies Kurzweil's claims on that score, but he's put them on the table. He goes on to assert (p. 6), "It's becoming increasingly clear the mechanized intelligence can solve a rapidly expanding repertoire of problems." OK. He mentions Big Blue's chess victory over Kasparov in 1997 and Watson conquering Jeopardy! in 2010. Exciting stuff, yes.

We're on the very of having computer systems that understand the entirety of human "natural language," a problem that was considered a very tough one only a few years ago. Just talk to Siri on your iPhone and she is likely to understand your voice, give you the right answer, and help you make an appointment.

On this one I line up with the kids who think that understanding natural language is still a very tough problem, and, yes, I'm aware of the remarkable progress that's been made since Cowen published this book only six years ago. But understanding natural language (I don't know why Cowen used scare quotes there when he should have put them around "understanding") just gets more and more difficult the more we're able to get our machines to do. Back in 1976 I co-authored an article with David Hays in which we predicted that the time would come when a computer model would be able to "read" a Shakespeare play in a way that would give us insight into what one's mind does while reading such a text [3]. We didn't offer just when this might happen, but in my mind I was thinking 20 years.

Well, nothing like that was available in 1996. Not only that, but the framework in which we'd hazarded that prediction had collapsed. Whoops! We still don't have machines that can read Shakespeare in an interesting way, nor do I see any on the horizon. And yet you can query Siri and get useful answers on a wide range of topics, something that wasn't possible in 1976, though the Defense Department spent a lot of money trying to make it happen (and I read those tech reports as they were issued).

What's going on? There's a lot I could say, but not here. And certainly others know much of the story better than I do, especially the technical details.

It's complicated, it really is. Consider a somewhat labored comparison. Henry Hudson made landfall in North America in 1609, not very far from where am now (Hoboken, he made land in what is now Jersey City). He sailed up the Hudson river I don't know how far, but pretty far - he was looking for a passage to the Orient, after all. But, there's a certain kind of land and climate in the Upper New York Bay where Hudson landed. How could he have know that, by heading due West, you would encounter mountains, then a vast prairie and then, after that, rugged high mountains, and then desert, more mountains, and then the Pacific Ocean? Surprise after surprise after surprise.

Well, with AI, and computing more generally, it's like that. It's a new territory, large and various, and what we've already encountered doesn't seem to be a reliable guide to what's in territory we've not yet encountered. Cowen has his guesstimates and I have mine.

As far as I can tell, his argument about genius computers coming up with unintelligible, but nonetheless valid, scientific theories, can safely be separated from his more general arguments about computing and work. Computers will become more and more important in the workplace and what we see in Freestyle chess may well be a precursor to the style of work in many jobs. Humans will work in tandem with computers and those computers are going to be doing more than keeping records and processing words. Much more.

In the course of making an argument about the future of economics Cowen argues that theory is giving way to data (p. 226): "If I see an important economics paper, circa 2013, odds are it was based on a clever way to find or generate a new data set, not a new theoretical idea." He goes on to note, "Steven Levitt writes papers on baby names, sports, and whether teachers cheat [...] Gary Becker has spent decades studying the family and household behavior [...] Daniel Kahneman, who is a psychologist, has won a Nobel prize in economics ..." This leads up to (p. 227):

We're not far away from having a single de facto, more or less unified, empirical social science. In that social science, researchers invest a lot in learning empirical techniques and then invest some marginal energies in the simpler theories that surround their chosen field of study. Finally, they spend their research time looking for new data sets, or looking to create that data, whether by detective work or by lab and field experiments.

But I don't believe that theory is going to wither. I don't think, for example, that we can understand human socio-cultural evolution with the body of theories and models we currently have. But I don't need to mount an argument on the score here; nothing I say depends on it.

Finally, let's look at the twelfth and final chapter, "A New Social Contract?" For example (pp. 229-259):

We will move from a society based on the pretense that everyone is given an okay standard of living to a society in which people are expected to fend for themselves much more than they do now. I imagine a world where, say, 10 to 15 percent of the citizenry is extremely wealthy and has fantastically comfortable and stimulating lives, the equivalent of current-day millionaires, albeit with much better health care.

Much of the rest of the country will have stagnant or maybe even falling wages in dollar terms, but a lot more opportunities for cheap fun and also cheap education. Many of these people will live quite well, and those will be the people who have the discipline to benefit from all the free or near-free services modern technology has made available. Others will fall by the wayside.

The slogan "We are the 85 percent!" probably won't sound as compelling as the Occupy Wall Street version. It will become increasingly common to invoke "meritocracy" as a response to income inequality and whether you call it an explanation, a justification, or an excuse is up to you. Since the self-motivated will find it easier to succeed than ever before, a new tier or people from poor to underprivileged backgrounds will claw their way to the top. The Horatio Alger story will be resurrected, but only for those segments of the population with the appropriate skills and values, namely self-motivation and he ability to complement the new technologies. It's in India and China that the rise of a new middle and upper class is reflecting this trend most clearly.

I'm going to accept all that more or less a face value. And I think Cowen's right to point to China and India. But what will become of Africa?

I am forecasting a few particular changes, starting with the most obvious and ending with the least obvious:

- We will raise taxes somewhat, especially on higher earners.

- We will cut Medicaid for the poor (but not so much Medicaid for the elderly) by growing stingier with eligibility requirements and with reimbursement rates for Medicaid doctors, who will impose queuing on program beneficiaries.

- The fiscal shortfall will come out of real wages as various cost burdens are shifted to workers through the terms of the employment relationship, including costly mandates.

- The fiscal shortfall will come out of land rents; in other words, some costs of living will fall as people begin to live in cheaper housing.

- We'll also pay off growing debt by spending less of our money on junk and wasteful consumption.

That's operating from a pretty simple theory of US politics that says "old people get their way." The corollary to that theory is "in the future they will get their way all the more."

Again, I'm going to go along with that. That fact is, while I'm pretty sure I can argue with him on AI, here we're on his home turf. He knows it much better than I do.

If you think about it, we really shouldn't expect rising income and wealth inequality to lead to revolution and revolt. That is for a very simple psychological reason: Most envy is local. At least in the United States, most economic resentment is not directed toward billionaires or high-roller financiers-not even the corrupt ones. It's directed at the guy down the hall who got a bigger raise. [...] Right now the biggest medium for envy in the United States is probably Facebook, not the yachting marinas or the rather popular television shows about lifestyles of the rich and famous.

Well, maybe "yes" maybe "no". I'm assuming that by "revolution and revolt" Cowen means violent insurrection like, for example, revolutions in America (1776), France (1789), or Russia (1917). I don't see that in the future. But it's a complicated and interesting world, is it not? I'll have more to say about this in the next section.

This is how Cowen concludes the book (pp. 258-59):

The American polity is unlikely to collapse, but we'll all look back on the immediate postwar era as a very special case. Our future will bring more wealthy people than every before, but also more poor people, including people who do not always have access to basic public services. Rather than balancing our budget with higher taxes or lower benefits, we ill allow the real wages of many workers to fall and thus we will allow the creation of a new underclass. We won't really see how we could stop that. Yet it will be an oddly peaceful time, with the general aging of the American society and the proliferation of many sources of cheap fun. We might even look ahead to a time when the cheap or free fun is so plentiful that it will feel a bit like Karl Marx's communist utopia, albeit brought on by capitalism. That is the real light at the end of the tunnel. Such a development, however, will take longer than I a considering in the time frame of this book.

In the mean time get ready. The basic look of our lives, and the surrounding physical environment, hasn't been revolutionized all that much in forty to fifty years-just try viewing a TV show from the 1970s and the world will seem quite familiar. That's about to change. It is frightening, but it is exciting too.

It might be called the age of genius machines, and it will be the people who work with them that will rise. One day soon we will look back and see that we produced two nations, a fantastically successful nation, working in technologically dynamic sectors, and everyone else. Average is over.

OK, average is over. I'd stick scare quotes around "genius", but surely amazing machines will be central to the next phase of human socio-cultural evolution. As for those two nations, read on.

At this point we move from "reality" to "fiction". I use the scare quotes, not out of capitulation to postmodernism (whatever that is), but out of caution. While Average is Over is based on real things and events, it takes a look at the future and so is, in some sense, fictional. Cowen is telling us what he thinks will really happen, but it hasn't happened yet and he might be wrong. Now I want to turn to Kim Stanley Robinson's New York 2140 [4], a work of deliberate fiction which is about the future, as the title indicates. When I decided to read it, I did so because I wanted to think about the future in as "real" a way as possible. I'd read Robinson's Mars trilogy some years ago and knew him to be a meticulous writer of plausible science fiction.

Western thought has a long tradition of argument about the truth status of fiction that goes back to Plato. He thought poets were liars and so not to be trusted, but that didn't keep him from offering fictional dialogs as the highest form of truth. But we need not rehearse those arguments here. It is enough for our purposes to know that Cowen himself sees novels as a vehicle for truth. In an unpublished essay from 2005, "Is a Novel a Model?" [5], Cowen explores the value of novels as sources of economic insight.

When evaluating economic welfare, the question remains whether we should use a wealth-based view or a happiness view. Novels make the happiness-based view more plausible, both by portraying the complexities of human welfare, and by showing how the rich are not always happy. When the very poor escape extreme poverty, they are better off. It is never fun to starve. Yet literary figures are not generally happier as they become wealthier. Instead we often find that money and avarice corrupt happiness, as expressed in tales by Balzac, Dickens, Proust, Flaubert, and many other writers.

And that's what I was after when I read New York 2140, a "happiness view" of a future in which global warming has brought about a considerable rise in sea level. One look at the book's cover made it clear that that's the kind of world Robinson was exploring. The seas had risen fifty feet, putting Lower Manhattan under water, though many buildings projected above that level and so were still used, both as places as business and as homes. As I read that book it became clear that it was, on the whole, an optimistic book, though not mindlessly so. I could imagine living in that world and being happy in it-depending, of course, on my position in that society.

Let's look at another passage from Cowen's essay (pp. 10-11):

Some kinds of fiction resemble models. Some science fiction stories, for instance, embody model-like thinking. The author writes down a description of some new technologies to be found in a hypothetical world. The author then traces through the effects of these technologies and outlines how things would work, or outlines an equilibrium, in economic terminology. That equilibrium is then "disturbed" by some new change, such as alien invasion or a new technology. The bulk of the novel then traces through the effects of the change, performing a kind of comparative statics exercise.

Though New York 2140 is certainly science fiction, it's not quite like that. There are certainly new technologies in this world, new building materials and techniques, some interesting AI, I'm thinking particularly of the pilot for an airship that's central to the story (though no "genius machines" proposing new cosmologies). But Robinson doesn't focus on the technology. He's interested in how people live and, in particular, in political change. Yes, the technology's different, and the ocean's have risen, but the political and social institutions are much like those of our world. In particular, inequality is still there and perhaps even stronger, something Cowen has discussed at some length in Average.

The disturbance that interests Robinson isn't technology; it's the weather - as befits a post climate-change book. By the time you've read half to two-thirds of the book it is clear that he is setting us up for a revisionist replay of the financial collapse of 2008. [Warning: Major spoilers ahead.] Hurricane Fyodor is forming and if it makes landfall at New York City there's going to be a disaster. It does and it triggers major problems in the real estate market which ripple out across the county (p. 531):

Strategic defaulting. Class-action suits. Mass rallies. Staying home from work. Staying out of private transport systems. Refusing consumer consumption beyond the necessities. Withdrawing deposits. Denouncing all forms of rent-seeking. Ignoring mass media. Withholding schedules payments. Fiscal noncompliance. Loud public complaining.

What happens? This that and the other such that a polity-wide coordination problem is (spontaneously) solved with a resulting outcry forcing the federal government to nationalize the banks (pp. 601-602):

Thus in February 2143, Federal Reserve chair Lawrence Jackman and secretary of the treasury, both of course veterans of Wall Street, met with the big banks and investment firms, all massively overleveraged, all crashing, and they outlined a bailout offer amounting to four trillion dollars, to be given on condition that the recipients issue shares to the Treasury equivalent in value to whatever aid they accepted. The rescues being necessarily so large, Treasury would then become their majority shareholder and take over accordingly. Earlier shareholders would be given haircuts; debt holders would become equity holders. Depositors would be protected in full. Future profits would go to the U.S. Treasury in proportion to the shares it held. If at some point the recipients of aid wanted to buy back Treasury's shares, the deals could be reevaluated.

In other words, as a condition of bailout: nationalization.

Oh, the tortured shrieks of outraged dismay. Goldman Sachs refused the deal; Treasury promptly declared it insolvent and arranged a last-minute fire sale of it to Bank of America, just as it had arranged the sale of Merrill Lynch a century before. After that, Treasury and the Fed offered any other company refusing their help good luck in their bankruptcy proceedings. [...]

Finally Citibank took the deal offered by Treasury and Fed, and in rapid order all the other banks and investment firms also took the deal. Finance was now for the most part a privately operated public utility.

Various new taxes were enacted and all of a sudden the Federal government was swimming in money (pp. 602-603):

These new taxes and the nationalization of finance meant the U.S. government would soon be dealing with a healthy budget surplus. Universal health care, free public education through college, living wage, guaranteed full employment, a year of mandatory national service, all these were not only made law but funded. They were only the most prominent of many good ideas to be proposed, and please feel free to add your own favorites, as certainly everyone else did in this moment of we-the-peopleism.

And how does that work out? We don't know (p. 604, the book ends on 613):

So no, no, no, no! Don't be naïve! There are no happy endings! Because there are no endings! And possibly there is no happiness either!

As I've already indicated, the world of New York 2140 seems roughly compatible with that of Average is Over. Cowen doesn't put times to his predictions, but I'd guess he's looking maybe a bit past the middle of the century; and he has nothing to say about global warming, which is not directly relevant to his discussion. Robinson is thinking farther into the future and after major warming, giving us plenty of time and circumstance to tweak parameter values from those imagined by Cowen. Average is Over and New York 2140 propose recognizable variants of the same underlying social and technological forces.

What would Cowen think of the nationalization of the banks? Don't know, but he's no fan of big government. What about all those expensive new government programs? I think he'd be skeptical.

For that matter I don't really know what I think about those things either. It's not my imagined future we're dealing with, it's Kim Stanley Robinson's. For the moment I'm satisfied to think about that world. It's certainly easier than trying to imagine some other future in the detail Robinson has lavished on that one. And the detail matters. Sketching out a desirable future in general terms is easy. It's the details, and their connection to the present, that's tough. It's those details and that connection that make the exercise "real". Perhaps the best way to figure out just what I think is to start with New York 2140 and work from there.

Moreover, it's not like Robinson's gotten that world locked down. In particular, at the very end he indicates the existence of dimensions in that world that he hasn't dealt with. That's what interests me.

In the very last chapter we're deep below the surface in a nightclub named after Mezz Mezzrow, a prototypical hipster from the second quarter of the 20th century known for his drug dealing - in certain circles a joint was known as a Mezz.

Everyone in the room is now grooving to the tightest West African pop any of them have ever heard. The guitar players' licks are like metal shavings coming off a lathe. The vocalists are wailing, the horns are a freight train. (611)

And then another musician joins the band, - "Tall skinny guy, very pale white skin, black beard" - and when he starts to play (612):

The other horn players instantly get better, the guitar players even more precise and intricate. The vocalists are grinning and shouting duets in harmony. It's like they've all just plugged into an electrical jack through their shoes...Crowd goes crazy, dancing swells the room.

Where'd THAT come from? said I to myself. Had Robinson been toking on a Mezz or two?

That whole scene struck me as being uncharacteristic of the novel. When I read it I realized I'd been seeking such scenes all along. Why? Because that's how you build community, that's why [6]. Robinson offers this scene as a reward for work well done, which it is, but the fact is that the social solidarity necessary for his revolt against the banks depends on hundreds of thousands of such encounters distributed across space and time.

It seemed to me that someone needed to write a counter or complementary novel, one set in the same world, but which is centered on those rituals of community. While we're at it, why not run that world forward another decade, say to 2150, and center it somewhere else. Where?

Kisangani, Democratic Republic of the Congo, that's where [7].

It's not in West Africa, though. It's in central Africa, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and is 1300 miles inland from the mouth of the Congo. It was founded in 1883 by Henry Morton Stanley and became known as Stanleyville once the Belgians colonized the Congo. It entered literary history as the Inner Station of Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness. It is the heart of "Darkest Africa". As such it is the imaginative and symbolic antipodes of New York City's "Great White Way," as the Broadway theater district was known in the first half of the 20th century.

That symbolic valence is what brought Kisangani to mind. If we're going to imagine a new form of human society - if indeed that's what we're up to (it's what I'm up to, no?) - where better to center it?

But that alone would not be sufficient. There are other considerations. Symbols and mythology, after all, have to be grounded in something.

Setting aside the Congo's troubled history, which would have to play into this extension and revision of Robinson's world building, Kisangani is currently a major commercial and transportation center. It is also home to 250 tribal groups. Back in 2007 the Chinese made a deal to finance a major road between Kisangani and Kasumbalesa on the border with Zambia, among other projects, in return for rights to timber, cobalt and copper [8]. What will the Chinese be doing there in 2150? What of the fate of those 250 tribal groups? For that matter, what of Pan Africanism? And music, what of that?

Now, think about this: Last year Cowen was in Ethiopia, which is of course in a different part of Africa - northeast of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, separated from it by South Sudan - where he befriended a guide whom he calls Yonas [9]. He decided that he would send his royalties for Stubborn Attachments (2018) to Yonas, who aspires to open his own travel business. Assume that Yonas does so, and that his business is successful, perhaps wildly so. Perhaps in due course he will send a child to China for a college degree. This child then returns home and joins the family business, perhaps deciding to branch out and establish an office in Kisangani to facilitate travel between China and central Africa. That brings us to the middle of this century. What happens to Yonas' descendants over the next century?

And so it goes. Detail upon detail upon detail, each linked to the other, some anchored in the present, while the rest fan out into the future.

Will I actually write this book, Kisangani 2150? Who knows? At the moment it is a convenient rubric under which I can organize thoughts and materials about the future [10]. And if I actually decide to write a book I'm likely to pretend to be a historian living in 2200 who is writing some kind of history about the last half of the twenty-second century.

Appendix: Who cares about computer chess?

Here's an interesting observation from chapter 8, "Why the Turing Game Doesn't Matter" (p. 156):

Despite the humans on the teams, even Freestyle chess isn't very popular, not even by the standards of the chess world. Some chess traditionalists are uncomfortable with the fact that some top Freestyle team members aren't very good at traditional chess, but I don't think that is the main problem. The anonymity and shifting names of the teams make it harder for fans to follow the contests and identify with favorites. It is more difficult to construct narratives about the players, their career arcs, and their personalities and emotional struggles. It doesn't fit the standard model of heroic achievement and struggle against adversity.

[1] Here's a post where I discuss the status of chess as an intellectual laboratory, "What about chess? What does it tell us about history? [path dependence]", New Savanna, August 8, 2019, https://new-savanna.blogspot.com/2019/08/what-about-chess-what-does-it-tell-us.html.

[2] For a general guide to my thinking about cognitive ranks, "Mind-Culture Coevolution: Major Transitions in the Development of Human Culture and Society", New Savanna, November 20, 2018, https://new-savanna.blogspot.com/2014/08/mind-culture-coevolution-major.html.

[3] William Benzon and David Hays, "Computational Linguistics and the Humanist", Computers and the Humanities, Vol. 10. 1976, pp. 265-274, https://www.academia.edu/1334653/Computational_Linguistics_and_the_Humanist.

[4] I've discussed the book in William Benzon, New York 2140, Back to the Future, Working Paper, June 2019, 30 pp., https://www.academia.edu/39720382/New_York_2140_Back_to_the_Future.

[5] Tyler Cowen, Is a Novel a Model? 2005, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228642839_Is_a_Novel_a_Model.

[6] I've argued that at length and considerable detail in Beethoven's Anvil: Music in Mind and Culture, Basic Books, 2001. You can download prepublication version of two chapters here, https://www.academia.edu/232642/Beethovens_Anvil_Music_in_Mind_and_Culture.

[7] Kisangani, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kisangani.

[8] China opens coffers for minerals, BBC News, September 18, 2007, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7000925.stm.

[9] Cowen has several posts about Yonas at Marginal Revolution, https://marginalrevolution.com/?s=yonas.

[10] I'm connecting those thoughts and materials at this link, https://new-savanna.blogspot.com/search/label/Kisangani2150.