Author Frank Delaney

"The Most Eloquent Man in the World." - NPR

“Every legend and all mythologies exist to teach us how to run our days. In kind fashion. A loving way. But there’s no story, no matter how ancient, as important as one’s own. So if we’re to live good lives, we have to tell ourselves our own story. In a good way.”

- from 'The Last Storyteller'

Irish-American novelist Frank Delaney has been telling the story of his native country through historical fiction for decades. A writer, broadcaster and James Joyce scholar, Delaney has been called by NPR "The Most Eloquent Man In the World."

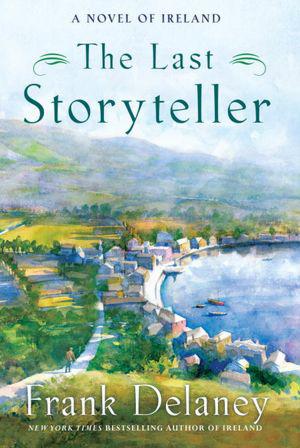

His most recent novel, 'The Last Storyteller,' is the final installment in his Venetia Kelly trilogy. A mixture of ancient Irish folklore, eerily similar modern recreations of these stories and the beginnings of the Irish Republican Army, the intertwining plot lines revolve around main character Ben MacCarthy, the latest in a long line of seanchis, traveling collectors of folktales. His predecessor, John Jacob O'Neill, realizes he has grown too old to carry on. He is ready to pass the torch on to Ben, teaching him what he will need to know in order to carry on the tradition for posterity.

Venetia Kelly, Ben's former wife, still holds his heart in her hands, though they've been separated for decades. He struggles with the feelings he still holds for her, though she's married to another man, raising Ben's twin children. Learning her new husband treats her violently, Ben must decide what action to take, his fiery temper threatening to lead him into committing an act of violence against the man he despises, while at the same time violence in Ireland itself is unfolding.

'The Last Storyteller' is a deeply felt, moving tale of ancient tradition colliding with the onset of The Troubles, a period in which Ireland engaged in a long, bloody civil war. Hatred and love, coupled with tradition and a land torn apart, 'The Last Storyteller' is an epic historical novel of Ireland told by one of its finest writers.

Mr. Delaney very kindly granted me an interview, taking time out of his busy schedule, for which I am incredibly grateful:

1). Could The Storyteller be set anywhere but Ireland? Would any other setting compare in intensity of history, wealth of folklore?

Naturally, chauvinistically, I'd like to think that it could not be set anywhere but Ireland! But, let me be Irish, and contradict myself immediately. First of all, I try to write for a universal audience. If the definition of the novel is “a prose account of the human condition” then we might as well make it global, might we not? Secondly, years of reading mythology from all around the world, and from time immemorial, has taught me that "people are people are people" and that the story of mankind, as reflected in mythology, has shared long, wide, and colorful strands everywhere. As I say in the Author's Note to The Last Storyteller, “mythology was a bible ever before there was a bible.” So, the answer to your question has to be that this is a story you could find in Alaska, India, Canada, Sri Lanka, Norway – whereever we have placed our feet.

2). How has Ireland changed in your lifetime, or has it? Can The Troubles ever be relegated to history?

Ireland has changed beyond recognition in my lifetime. It has changed politically, socially, spiritually, and culturally. I've always believed that the change began in earnest with the 1963 visit of President Kennedy. His youth, his vigor, his godlike glory showed my generation (I was 20) what was possible. Soon after, Ireland's politicians began to reach out to the world to invite companies in on tax holidays and we began to grow an economy. Next came the contraceptive pill, which loosened social behavior as never before. Shortly after this, scandals hit the Catholic Church like rockets – scandals of embezzlement and child abuse; at the same time, Northern Ireland and the civil rights issue exploded. Now we had a melting-pot to be sure. And how it boiled! For 30 years people fought each other in the streets of that part of the country still under British rule, and only when President Clinton came to power was the matter settled, if somewhat uneasily. By then, the full disgrace of the Catholic Church was underway and people quit worship in droves. To cap it all, an era of unprecedented wealth, the famed Celtic Tiger, began to collapse, and the country is now fighting its way out of bankruptcy. At the moment, there is no violence in the politics; it rumbles from time to time, but given my own personal experiences as a reporter during the worst of the Troubles, I'm grateful for even an afternoon of quiescence.

3). What drives you? What ignites your passion?

Good question – easy to answer! Writing drives me. Writing ignites my passion. The challenge of telling a good story clearly and, I hope, in excellent and vivacious language, across a cultural arc that is as wide as I can make it – that gets me out of bed with delight every morning of my life. Just think of it – the very notion of providing a reader with a book that they find enriching and rewarding is a privilege that I try to service every day.

4). Should we fear technology replacing books? Are you a fan of the digital era?

I'm a fan of anything that enables and advances reading. Technology holds no fears for me – I have a Kindle and an iPad. I read on both and I also have a stack of books on my bedside table. Since the e-reader first began to appear, I have always taken the view that it was “as well as” and not “instead of.” In any case, the book as beautiful object has always been powerful to me – for instance, I have long been a fan of the Folio Society, that deliciously enriching producer and purveyor of beautiful books and have dozens if not hundreds of their gorgeous titles on my bookshelves.

5). As a native Irishman, how do you feel about the pre-packaged Irish stereotype on St. Patrick's Day, the declaration everyone's Irish?

You shouldn't have asked this question! I admire the parade organizers and the parade marshals, and the participants in the parades, the dancers and the pipers and the marchers, who bring such pleasure and such delight to the notion of being Irish all across the United States and indeed the world. It remains extraordinary to me that an island not more than 33,000 square miles in size should be able to have its own national day once a year – what a size of personality that is! So I like the declaration that everybody is Irish for a day – but here comes the warning. I loathe the idea that to be Irish is to be drunk and vomiting and comatose from eight o'clock in the morning on as many streets across the United States as you can find. That's racist behavior, stereotyping the Irish as drunk.. The people who do that offer no representation of anything Irish that I know to be the general ethos of our country, and I wish they would go and throw up in their own yards and stay away from the sweet and good-hearted celebrations of our native saint and our culture.

6). Do you have a dedicated writing space and/or set hours you work? (Maybe the question should be, is there any time you aren't working…)

The second half of the question is the correct perception! I have two desks – one in our Connecticut home and one in our New York office. Insofar as decent social and marital behavior will allow (!) I am at those desks as often as I can be. As to hours of work – I find that I like best the work that I do earliest in the day. Over the years I've tried to refine as much as possible what kind of work I do in which period. So I reserve the morning, especially the early morning, for original composition, and try to do the rewriting at other hours of the day. But when a book is nearing an end, all those rules go out the window, and I write all the hours I need, sometimes ten, twelve, fourteen hours at a stretch.

7). Longhand, computer or typewriter? Which is your preference?

I tend to start a book in longhand – I make notes, I filled page after page of notebooks with odd jottings, observations, questions and inquiries. Out of this a general shape and idea seems to arrive somewhere, and I begin to write the first third of the book on the computer. That first section can take four to five times as long as the remaining two sections together.

8). Silly question, but why Joyce? Why devote so much time to lovingly explicate Ulysses, page by page? Thank you, by the way, but why?

Why Joyce? Why not?! Seriously – he remains, for me, one of the greatest writers of all time, and since I discovered him for myself, and began to revel in the joy that I find in him, I felt almost obliged to find a way of spreading that enjoyment. I know, I know, it seems nuts – but since I first started unpacking Ulysses phrase by phrase, with the express intention of leaving not a reference unexplained by the time I've finished, I've had something else wonderful happen to me. Apart from the hundreds of thousands of downloads of the weekly podcast, and the thrill of the enjoyment that people are good enough to share with me when they write to me, I am learning the most fabulous new raft of knowledge. Joyce had an extraordinary mind – he may have been one of the best read people of all time, and by taking the time and trouble to interrogate his – often very dense – references, I am learning what he knew. And passing it on. I can scarcely imagine a more enjoyable task.

9). How strong is the pulse of literary fiction, criticism and serious examination of literature in the 21st century? Who are today's shining literary lights?

Great question! People have been saying for generations, “Oh, the novel is dead.” Well, it ain't – nor is that wonderful American invention, creative nonfiction, nor is biography, nor is political writing. And as well as the books, the commentariat is alive and well. In fact, there's an argument to be made that it's healthier than ever, because we now have this wonderful new creature, the Literary Blogger. I'm a massive fan of this gorgeous animal, with all its fur and feathers – for a number of reasons. My main complaint about the general direction of literary criticism over the last century has been – and Joyce is a case in point – that it tended, in its lofty tone and often impenetrable language (not to mention occasional vendetta behavior), to be antidemocratic, to keep certain areas of literature to itself, whereas my own passion is for as many people as possible to be reading as widely as possible. The Literary Bloggers have no axes to grind, they're not protecting their reputations, they don't fear being sneered at by other critics, they're reading what they want to read, writing what they want to write, and they don't want to keep what they enjoy to themselves. They want to share. They want to expand the constituency of reading. They want to hail and applaud good writing. To my mind this is a very significant development – uneven, I grant, here and there, but, dammit, not as uneven as the generations of formal literary critics, and the blogging intention is so good and so worthy of loud vocal support that you can call it truly a new and, to my mind, incomparably welcome development in the world of reading and writing.