The career of Guillermo Kuitca (Buenos Aires, 1961) began at nine years old when he entered the workshop Ahuva Szliowicz supported by his mother, a psychoanalyst, Mary Kuitca but especially by his father, an accountant, Jaime Kuitca. From here, he left at 18 years old, havign converted into a precocious painter: he had his first solo exhibition at the age of 13 and taught painting classes. The interest in film, music, literature and architecture is present in his work. Even, his passion in theater is present. He is the author, director and set designer. His work is present in the collections of major museums including the Metropolitan Museum, MoMA, Tate Gallery ... But the most interesting thing of Kuitca, is that thanks to him, Argentine artists future generations have formed. In 1991 Kuitca creates Scholarships where they study and work in disciplines related to the visual arts.

With a precocity like yours, what memories have remained in those beginnings and who has especially marked you?

Undoubtedly, the figure of my father has been very important in this case. He had a great illusion that I become an artist. His interventions were very subtle, but I remember when I went to buy the first fabrics, the first easel and first brushes, I always went with him, and I imagine it also had a notable mark on that contribution on his behalf. Many years later when I was already a painter totally dedicated to this and absolutely committed, dad told me that in his youth he had tried to paint. He was from a poor family, that is, stealing the hairs from his father´s shaving brush as well as cooking oil, luckily things I learned much later luckily, because children are very sensitive to every little thing.

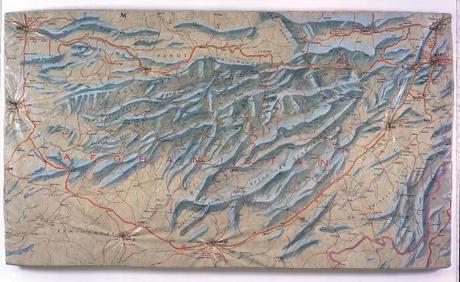

His pictorial series have gone to the beat of their own changes but also the historical situations: this applies to "Nobody forgets anything" (1982) in pure conflict of Falkland´s war. For this series he locks himself in his studio using for his works whatever material that lies at hand: doors, wood or fabric. It is a very intimate series but also a political and historical view of the world, representing over and over again, the bed as the central image, women and heartbreaking scenes. The bed is a symbol that has accompanied him in his work as the installation Untitled 1992 representing 52 mattresses painted with maps.

What is the meaning of eternal recurrence of this object in your work? Has your concept changed in time?

I saw on the bed as if it were a vehicle which I could use to move through human experience and through my work, as if the bed had wings or wheels, as to say, the image has neither one nor the other, it is a rectangular with legs but has the potential to move through time and space.

There is something very basic in the same image that remains as a kind of heart that which is in the works and I think that subsists until late, up until 2013 with a big play called Double Eclipse which has a number of beds and it is as if there was something from that first experience, from that bed from the year 1981-1982 that is maintained. Of course my views on this subject is changing, extracting excessive forms, of conceptual adhesions: psychological, political, or sentimental things. How to turn the bed into a rectangle as if it were the plan of where life happens instead of the demarcation of a house, of human experience, like taking a most essential point possible, but that concept I would say almost survives along those in which is the human experience, birth, death, sex, sleep, illness, reading ... this stunning cluster of intimacies that happen. It was from the most sublime to the most banal. So I would say that more than the evolution of the concept, it was like taking adhesions that had stuck through time. The bed as pictorial representation is almost like a perfect equation that produces a very simple representation, an absolute inclusion of a beneficial huge space use.

Psychoanalysis has been present in his life from an early age. This was assisted by his mother, and a childhood marked by such a therapeutic method, whose meetings he went to unpleasingly. If the germ of art is in the unconscious, which is hidden deep in our personality, this really is a way to manifest symbolically, says Freud, through dreams; also by spontaneous writing or scribbles where aesthetics or morals of our conscious are not involved. Both are used in his works. His Diaries series are paintings done on canvas where scribbles, drawings, notes and paints over months of his daily life. These involuntary diaries and dreamscapes in many of his works, in which the figures live in half-empty spaces with disproportionate scale, disjointed scenes, surreal, leave a unsettling imprint.

The most intimate, the product of pure thought, emerges in your paintings. Does painting provide knowing oneself? What does public display make you feel?

Interesting paradox ... because while I like your version, for me, and I guess that for many artists it does not rule out a process of self-knowledge, there is definitely an inner in stake and therefore accessible. It is also true that for me, the power of the artwork is what happens in privacy that is created between the work and the viewer. Therefore, the work is not what is between the viewer and I, that is, the access to be able to reach me, but for me the strongest aesthetic experience is the relationship created between the work and who looks upon it, therefore I tend to disappear in that scene. I think that trying to look into the work of who is the artist, what is its truth, what the secret etc. is probably losing the richest of artistic experience, which is generating a particular privacy and that in general the painting produces this kind of miracle, which is what I see, that what happens to me, sometimes nothing happens, it's almost like a loving experience, like a secret between the work and I, and there it is the individual looking.

Of course it is entirely lawful and I accept all kinds of visions and do not think some are more legitimate than others. However, I think it is richer to be inquired into oneself that if the artist who made this work is hidden or vice versa, they are revealed in these details. On the other hand, everything is automatic work, for example, on the tables in my Diaries, rather than unconscious it is automatic work, it is a kind of fretting hand which marks things. It is not a test, in that sense I like when you think of the environment as rarefied as those that may be in dreams. But it is also true that there are many more dreams that dream interpretations and Freudian psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic techniques in a situation that is already more than 100 years old, has to do not with the dream, but to interpret the dream. In that sense one can dream without interpretation and I think the public of visual arts, the trained and untrained, either from exhaustion, disinterest or fortunately both inclusive, has abandoned the permanent temptation trying to interpret the artist or the work. I think there are thousands of possible accesses to a work and perhaps only one of them is interpretation. In my case, I was born in a family where psychoanalysis was very conventional, it was not uncommon. In a city where many people were analyzed, psychoanalysis appeared as something exceptional, I only saw it as a peculiarity with pros and cons. As you say, I could have analyzed myself, it was in a situation where the guys here in Buenos Aires in the modernity of the 60s, were sent to the analyst when they sneezed instead of going to the doctor to take an aspirin, everything was supposed as if it was psychosomatic, there was a kind of total abuse of therapy. And no guy liked to have their head stirred. Sometimes the access that the public has, the criticism, often is surprising because it is believed that the work hides oneself and actually it substitutes in a way that if you were aware of it, you could probably not do it.

His work has made a run in which the central reasons vary: the first works with distorted figures, quilted beds covered with maps, architectural and city levels, newspapers, maps, the empty luggage carousels or full emptiness displayed in unclaimed suitcases, are examples of what interested him at all times.

What is the relationship between the choice of these reasons and obsessions? Up to which point is art a cannel of them?

I think there should be a very direct line, of course work itself is already very obsessive but probably thinking about it is decoded at that time. I sometimes see my works of one time and like I almost infer what was in my head. Probably at the time of doing it, to which I say is not necessarily my obsessions at that time because the pictorial act itself is very demanding and absorbing and perhaps it is all that is needed to make a play, I myself am in the dialog with the paint on a kind of battle and sometimes bypasses a reflection of where my head actually is. Anyway, eventually I also see the lines connecting and that shoot out all these issues. Maybe when you mentioned the topics which had been my work, there is a huge body of work that is a bit of all these sequences of beds, city, the map and after, that leap to the luggage carousel, which are the theatres. The theater was a very important issue, somehow I had to make it rotate from the view of the stage, from the view of the audience, as a permanent return. When the first luggage carousel, it appeared as a backdrop, like a stage platform, almost as if it did not have to do with the representation. Of course I was interested in the unclaimed luggage desolation but the first luggage carousel was a bit of a response to the stage area, but then as the works marked their own way, the best you can do is not to resist and continue that footprint.

So these obsessions would be something to look back in time ...

The work is more intuitive. I do not know if I'm a good observer of my work. Of course I investigate and submit to all types of analysis, the cruelest possible but when I try to do that I try that there not be any intuitive element lost. If I question myself a lot of what I am going to do, I lose the purity, arbitrariness, intuition, nonsense, then that is a very important moment when the play opens on the other, the viewer, to another, but it is always a self-reflection. For me it is essential to be very concentrated and not ignore the signs that the work asks me, only think if the work is good or bad.

What Is art? Do you think art should also have a utilitarian purpose, such an instrinsic concept in our time? Or is it closer to what Schopenhauer said when speaking of art as a drug to temporarily ease the suffering that produces the continuous chain of needs and desires that our will cannot escape?

Obviously Schopenhauer times are not ours, but if art were a drug or balm, because Derrida said the drug was both a cure and a poison, that would make him in his own utility. In a fragmented world as still we live, art in its most sublime expressions does not produce such complete experiences that can soothe, solve all our frustrations, feelings possible. In this sense I do not think there is a situation of one hundred percent effectiveness in the human soul and I do not think that utility is the barrier that makes this not possible.

When we speak of art I do not know how we do it, as exchange value, as decoration, as thought, as a vehicle of ideas of all kinds of information, which would not be so negative. It seems that in the world we live in today, we have no chance to convert a single object into something (beyond money) in which condenses in a sense of neither profit nor absolute compensation. Art has helped us all who are close to the art to live of course, it has extended us the horizon, it has made us a better people at a certain point, or not, but it has helped us live when we have suffered and suffered and gone through everything that has happened around the world. It is very difficult to give an answer. I think art is still on that experience that happens between the work and the viewer and I think that it keeps some locked meaning. But not because it has not been revealed. There are writers who manage to tell their experience with art, but there is some privacy which is like the heart of art. There is privacy, like a measure of art in which its meaning is enclosed, I not know if one day we will access it or if it makes sense to do so.

You once said that you live with enthusiasm but also with despair. Could you tell us, what is now your dream? What are your lost hopes?

Regarding dreams, I have never done so many projects like this year, something that has taken me away from my studio. I guess my dream is to go back and lock myself in my studio and concentrate on my work. Hopelessness has to do with this, at least in recent years when you feel that things are never resolved, and the disappointments of those who govern us or the accumulations of power, I fear more the power accumulation than that of money, although it is almost the same, it is not exactly the same. That always leaves a bitter trace of reality that I live and I cannot complain because I am a very privileged person but I'm no stranger to it. The illusion always comes on a more personal level, starting this or that project or for the people around us. When we speak of illusion, we are reduced to the smaller, personal scale, and when we speak of despair we speak of the world, hunger ... It's funny how one shrinks their illusion to a scale and how it is extended with despair. In times of crisis, the artists will have to play a role which is to connect a disappointment with an illusion.

I have found that you are preparing an artist book with MoMA, could you anticipate something about it?

I am very surprised to know this. While I was waiting for you, I was working on it. I am developing some ideas, there is something very nice about this project which is the freedom of the material formatting, images, size, absolute freedom. It is an ideal situation but sometimes people need to know the limits to know where to go. With the publishing of this project we began to discuss and have working ideas. I have always been fascinated in artists' books. I'm not sure yet how it will be. My work is, generally, horizontal and I do not like horizontal books, I like vertical books, I fight with the book format in the catalogues. I seek that the structure of the books has images, it is a bit like painting, lately I have been painting murals and working in the corners of the rooms which fascinate me. It's a bit that game between the corners and these separations in what I'm thinking of right now.

Guillermo it has been a pleasure, I have learned about a lot of art in this conversation.

- Interview with Guillermo Kuitca by Elena Cue - - Home: Alejandra de Argos -