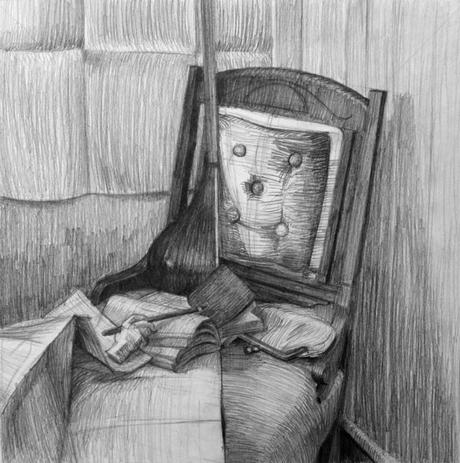

(Preparatory thumbnail drawing for current painting) © Samantha Groenestyn

While people readily brand drawings and paintings that look like something (representational, rather than purely abstract, art) as ‘realistic’ or ‘classical’, or, god forbid, ‘photographic,’ a word I seldom hear is ‘naturalistic.’ Where ‘realistic’ makes an appeal to the convincing appearance of things, ‘classical’ seems more a turning away from progressive and modern ideas. ‘Photographic,’ the least inspiring, removes this art another step from reality and our physical experience of things and likens the art to a mechanical process of mortifying a slice of time. None of these sound appealing—to be literal, anachronistic, or technologically redundant.

Naturalism is historically associated with variations on realism, often in reaction against more lofty subject matter or aggrandised themes, and sometimes attempting to align itself with the objectivity of the natural sciences. To baldly generalise, naturalist art historically set out to represent the physical world accurately and convincingly, but the word seems to carry some useful nuances not regularly referred to anymore. There is no weight of reality, of an appeal to existential absolutes, of universal correctness. Reality is a philosophically contested concept, and to describe one’s painting by appealing to reality is a frighteningly bold claim, and most likely metaphysically extravagant. A much more sensible and intellectually guarded claim would be to simply say, ‘I paint as accurately as I can the external world as it appears to me through my senses.’ Whatever may or may not exist or turn out to be real or true or foundational, it seems perfectly reasonable to represent one’s experience of the world within the limits of one’s ability to perceive it. A word like ‘naturalistic’ seems to capture this idea, describing the natural process of photons hitting retinas as well as the image this process imprints on the brain.

Further, this seems an eternal project, as photons continue endlessly to pummel retinas, and people continue to experience the world through their senses and to depict that experience accurately. This isn’t something reserved for a particular time in history, when all the important a priori truths were hammered out and proved by means of classical logic by muscular toga-clad types, but it seems like an ongoing project in which people of all times validly express the experience of their intersection with the physical world at a particular place and time. ‘Looking, seeing and constructing are specific to each generation,’ argues Nelson (p. 25); ‘they are conditioned by factors proper to the times, by inventions in optics and mechanical reproduction, but especially by aesthetic and social expectations about what people want to see.’

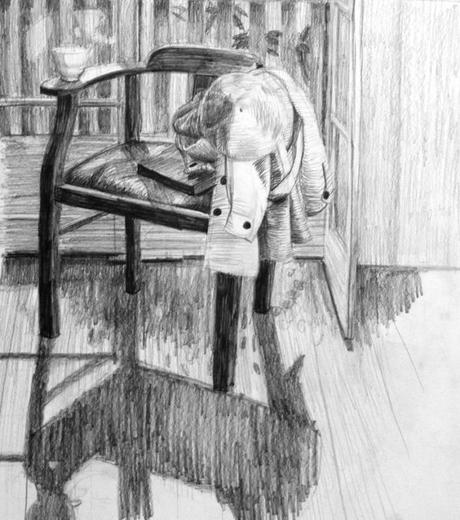

© Samantha Groenestyn

Perhaps instead of describing our work with words that are rather ill thought out antonyms of whatever is currently the mainstay of art, we should begin with our own intentions. When I look at modern drawings that fall closer on the spectrum to what I do—drawings of people that look like people, of objects that look like objects—there is something undeniably of their time about them. These people look like they belong to our time. Rubens’ people do not look like people that walk the earth today. They take on a magical sort of quality, a dreamlike appearance quite disconnected from my natural experience of the world. Was Rubens not as good as, say, contemporary American draughtspeople? Did he not know as much anatomy, or capture the personality of his subjects?

It stands out quite starkly to me that Rubens had a wildly different intent to people currently exploring naturalistic image-making. In fact, ‘naturalistic’ is not nearly the right word to describe Rubens’ representation of the world. His work, while representational, is highly imaginative, as Delacroix (p. 207) ruminates in his journals:

‘Rubens is a remarkable illustration of the abuse of details. His painting, which is dominated by the imagination, is everywhere superabundant, the accessories are too much worked out. His pictures are like public meetings where everybody talks at once. And yet, if you compare this exuberant manner, not with the dryness and poverty of modern painting, but with really fine pictures where nature has been imitated with restraint and great accuracy, you feel at once that the true painter is one whose imagination speaks before everything else.’

The natural world is not irrelevant to Rubens, but it is not king. It does not bound his work, or dictate what it may be, or determine his success by how accurately he creates an illusion of it. The natural world is a point of departure, a point of reference, an inspiration and in many ways a language or a framework—his painted worlds aren’t so far removed that our minds cannot compute them, and for the most part laws of gravity are obeyed (except by flying babies) and light acts predictably and bodies do not contort more than we would expect they are able.

Delacroix (p. 209) argues that ‘the imitation of nature … is the starting point of every school.’ He likewise considers it a matter of intent: does one intend to ‘please the imagination’ or to ‘obey the demands of a strange kind of conscience’? Rubens is faithful to nature to a point, but he doesn’t simply diverge from nature. He begins, rather, with an ideal, and wraps nature around this ideal as he sees fit, fleshing it out with great flourishes and enthusiasm. This act of imagination can never be out-dated or a boring relic of the past. It is reinvented by every living artist who grapples with the human form and its relation to the physical world, and it is this imaginative vision that contributes something new and meaningful to the tide of work that came before her. I am convinced that even naturalism will not get us out of this dirty little bind we’ve found ourselves in, but that idealism is a far stronger starting point.

© Samantha Groenestyn

In many ways, what I paint is certainly not natural, for I adapt the feel of the light to my idea of the mood of the piece, I morph the colours into a harmony that suits my purposes. I arrange the objects in improbable and thoroughly contrived ways to achieve pleasing compositional effects. I am not concerned with ‘capturing reality’ or presenting a truth to you. In fact, I openly present lies to you, carefully woven lies to manipulate your thoughts and emotions. Even in an interior, I am striving for an ideal, I am recreating my world through my imagination, and trying to show you the most fascinating bits of it.

And more—thinking this way changes the way that I draw, for my drawing ceases to be a task in accuracy, with nature as my assessor. Drawing becomes a powerful medium for new thoughts and new expressions; rather than functioning as a rather utilitarian exploratory tool it moves into the realm of visual poetry.

© Samantha Groenestyn

The ever-eloquent Delacroix (p. 208-9) says it so clearly:

‘The only painters who really benefit by consulting a model are those who can produce their effect without one. …

It is therefore far more important for an artist to come near to the ideal which he carries in his mind, and which is characteristic of him, than to be content with recording, however strongly, any transitory ideal that nature may offer—and she does offer such aspects; but once again, it is only certain men who see them and not the average man, which is proof that the beautiful is created by the artist’s imagination precisely because he follows the bent of his own genius. …

If therefore you can introduce into a composition of this kind a passage that has been carefully painted from the model, and can do this without creating utter discord, you will have accomplished the greatest feat of all, that of harmonising what seems irreconcilable. You will have introduced reality into a dream, and united two different arts.’

Let’s not lazily and belligerently appeal to reality, but let’s call on nature for a purpose, after we have determined our intent.

Delacroix, Eugene. 2010 [1822-1863] The journal of Eugene Delacroix. Trans. Lucy Norton. Phaidon: London.

Nelson, Robert. 2010. The visual language of painting: An aesthetic analysis of representational technique. Australian Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne.