Each day, dozens of articles are written about the importance of innovation in the business world. Most companies believe that their future survival depends on their ability to be innovative. For example, Danny Baer and Luc Charbonneau, write, "Innovation is the primary force that can catapult a company to market leadership and keep it ahead of its rivals." ["Ernst & Young Insights: The innovation engine: Your company’s success may depend on it," Financial Post, 1 February 2013] Vinnie Mirchandani, however, believes that talking about "innovative companies" is a silly idea. ["Companies do not innovate. People do." Deal Architect, 30 January 2013] He writes:

"Apple is Apple because Steve Jobs brought together an amazing team with Tim Cook, an operational genius, Jonathan Ive, a design genius, Ron Johnson, a retail genius, Philip Schiller, a marketing genius and many more. Apple is Apple because it leveraged the innovations created by people at Corning, Foxconn and countless other suppliers. Innovation happens at a cellular level [rather] than a 'company' [level]."

Although it may seem that Baer's and Charbonneau's position is mutually exclusive from the position expressed by Mirchandani, I don't believe it is. During the last U.S. Presidential race, Mitt Romney became infamous for declaring, "Corporations are people." He was ridiculed for the remark, but his point was that people are at the heart of corporate activities, including innovation. If, in fact, you equate a company with its people, then both positions (i.e., that companies and people can be innovative) can be reconciled. That really seems to be what Baer and Charbonneau are saying. They explain:

"As a business grows, you need to keep the spirit of creativity alive — it's too easy to snuff out the creative spark with a stifling layer of process and bureaucracy. Successful companies focus on more than just growth, profit and the bottom line. They build in new capabilities, functions or even departments that centre on creative, disruptive and sustainable ventures."

Obviously, the spirit of creativity and the creative spark can only be kept alive in people. The fact that they discuss new capabilities, functions, or even departments also aligns well with Mirchandani's point that innovation happens at the cellular level. If you buy into the concept that when talking institutionalized innovation you are really talking about how to create the environment, culture, and processes that will help make people more innovative, then you should have no trouble accepting the notion that innovation can involve a structured, repeatable process. Robert Brands, founder and president of Brands & Co. LLC, believes "a structured process must be put into place." ["Can Innovation Be a Structured, Repeatable Process?" IndustryWeek, 23 July 2012] He writes:

"Although it sounds counterintuitive to say 'structure' and 'ideation' in the same sentence, organizations need to conduct at least two ideation sessions each year in order to foster continued growth. A good innovation leader has the foresight to schedule regular ideation sessions year after year, and not just when sales are dwindling. Ideation, or idea management, is part of a long-term innovation effort that, if facilitated intelligently, leads to successful new products or services. Even if a small percentage of concepts make it through the process, the payoff could be significant for the company."

Brands also provides some recommendations about how a company can best structure those ideation sessions. He writes:

"Here are some tips for hosting ideation sessions that will lead to the best possible outcomes.

- Break up teams into people who know each other but are not 'that friendly' with each other in order to minimize groupthink.

- Vary the format as well as locations and times of ideation sessions. Predictability can kill ideation. Mix it up to get people out of their comfort zones.

- Accept ALL ideas and get them written down on the board. You never know when a concept can be recycled for future use.

- Build a database of ideas from which new combinations and solutions can be derived.

"By holding regular ideation sessions, your organization is adopting a proactive strategy in the new product development process."

I have two concerns with Brands' approach. First, it may lead employees to believe that new ideas are only wanted a couple of times a year and only in formal ideation sessions. Leaders need to ensure that their subordinates understand that there is no bad time to bring up a good idea. Second, his emphasis on ideation (i.e., coming up with ideas) isn't where most companies fail. Tim Kastelle notes that out of hundreds of organizations he has had his students assess, only about 5 percent of those organizations have had any difficulty coming up with new and good ideas. So coming up with ideas is rarely the problem. Kastelle agrees with Brands, however, that "it’s much better to think of innovation as a process than to think of it as an event." ["How to Manage Innovation as a Process," Innovation for Growth, 6 November 2012] Like Brands, he thinks of innovation as idea management. He explains:

"In order to innovate effectively, you not only have to generate great ideas, but you have to select the ones that you want to invest in, then execute them, figure out how to keep people inside the organisation committed as you go through the process, then get the new ideas to spread out in the world. And if one part of that process goes wrong, then your innovation efforts will likely fail. That's kind of scary."

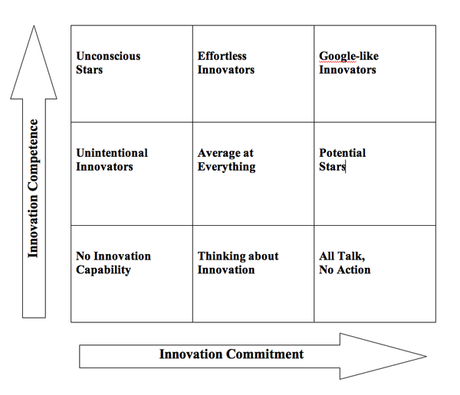

Kastelle indicates that he uses an "innovation value change" to help companies assess where they are in relation to innovation. He also uses an innovation matrix as depicted in the graphic below. ["Tools Don’t Solve Problems, People Do," Innovation for Growth, 16 February 2011] From the title of Kastelle's post, it's easy to see that he agrees with Mirchandani that innovation is all about people. In fact, Kastelle calls it "the last people-centric process" in the corporate world.

Kastelle asserts that the innovation matrix "is useful – because tools and skills are two separate things. You can increase one without affecting the other." He offers three lessons learned from using the matrix.

- "Innovation tools and innovation skills are two separate things: people often think that they can solve their innovation problems simply by finding the right tool. This is rarely true. In general, to improve innovation you have to improve skills and capabilities. Tools can be used to facilitate this process, but they can’t do it on their own.

- "One of the biggest obstacles to innovation is lack of time: if innovation is important, people need the time and space to work on developing, testing, and spreading new ideas. If you are a manager and you want your people to be more innovative, you have to give them the time needed to do this.

- "Tools don't solve problems, people do: this is why innovation is still people-centric. It's more important to remove obstacles to innovation than it is to give people tools.

Oana-Maria Pop, an Associate Editor at InnovationManagement.se, also believes that innovation must have a systematic approach. ["Systematic Innovation and the Journey Towards a Unified Innovation Management Standard," 19 November 2012] She indicates that there are four "key insights arguing in favour of a systematic approach to innovation." They are:

1. The Concept of Innovation is Becoming Broader and More Complex

... Innovation is undergoing a major shift. It can now start in emerging markets and not only in mature ones; it has become open, and collaborative allowing more and more areas of the organization to be involved. Paradoxically, broader involvement is not entirely good news. More participants in the innovation process mean more complex decision-making – a genuine burden when there is little guidance available.

2. Innovation Strategy and Culture Matter Enormously

In order to thrive, organizations need to have the relevant cultural component in place and this component involves securing the right attitude towards innovation. ... Companies need to ensure the correct and continuous integration of innovation in the overall company strategy.

3. Innovation does not just 'happen'

... With customer demand and competitive pressures increasing and operation excellence making entities leaner and leaner, the odds of innovation happening by chance have decreased. Evidence points towards a more proactive approach to developing new products, services and business models.

4. Confusion and its lasting reign

The final insight to consider is the puzzlement among entities – especially regarding what innovation is, what it can do and why it should be formally managed. Even companies at the forefront of new product or service development struggle to maintain a robust model that sustains innovation. In addition, organizations agree that they need to innovate more and also acknowledge the existence of a knowledge gap in terms of a systematic approach to their innovation processes.

Even if all the pundits agree that innovation is a people-centric process and that it is required if businesses are to thrive, there are no silver bullet solutions about how to institutionalize innovation. Baer and Charbonneau correctly assert that the innovation process must be tailored to the company (and that may mean you need to tailor it to the people in the company).