© Nick Brandt

I’ve been a bit mad preparing for an upcoming conference, so I haven’t had a lot of time lately to blog about interesting developments in the conservation world. However, it struck me today that my preparations provide ideal material for a post about the future of Africa’s biodiversity.

I’ve been lucky enough to be invited to the University of Pretoria Mammal Research Unit‘s 50th Anniversary Celebration conference to be held from 12-16 September this year in Kruger National Park. Not only will this be my first time to Africa (I know — it has taken me far too long), the conference will itself be in one of the world’s best-known protected areas.

While decidedly fortunate to be invited, I am a bit intimidated by the line-up of big brains that will be attending, and of the fact that I know next to bugger all about African mammals (in a conservation science sense, of course). Still, apparently my insight as an outsider and ‘global’ thinker might be useful, so I’ve been hard at it the last few weeks planning my talk and doing some rather interesting analyses. I want to share some of these with you now beforehand, although I won’t likely give away the big prize until after I return to Australia.

I’ve been asked to talk about human population pressures on (southern) African mammal species, which might seem simple enough until you start to delve into the complexities of just how human populations affect wildlife. It’s simply from the perspective that human changes to the environment (e.g., deforestation, agricultural expansion, hunting, climate change, etc.) do cause species to dwindle and become extinct faster than they otherwise would (hence the entire field of conservation science). However, it’s another thing entirely to attempt to predict what might happen decades or centuries down the track.

Human population trends in southern African countries 1960-2015

The first aspect is looking at what human populations have been doing in southern Africa over the last half century. No prizes for guessing the obvious — the human populations of the 13 countries (Democratic Republic of Congo, South Africa, Tanzania, Mozambique, Madagascar, Angola, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Malawi, Botswana, Namibia, Swaziland, Lesotho) making up ‘southern’ Africa have increased annually by an average of 1.16% from 1960 to today (73 to 320 million). The Democratic Republic of Congo has the region’s largest population at 77 million people.

As we showed previously, Africa is also the region expected to have the greatest increase globally in the human population over the coming century. If we take the subSaharan Region 2 from our 2014 paper, the projected increase to 2100 is over 5.5 times (to nearly 3 billion people). This is because Africa’s rate of fertility decline has been about 1/3 of that observed earlier in Latin America and Asia, and there is now evidence for a stalling of fertility decline in many African countries. In fact, a follow-up study estimated that the entire continent of Africa will have between 3.1 and 5.7 billion (95% confidence interval) by 2100. Wow.

I’ve done some preliminary analysis now looking at the effect of current human population densities on mammal diversity, and suffice it to say that this shows that diversity is negatively correlated with human density (after accounting for productivity, road density, and cropland intensity). I have a lot of work still to do on that particular analysis, so I’ll leave that there for the moment.

Of course, human population size is only one side of the ‘human pressure’ coin, with consumption being the other, inseparable dimension. Consumption can be of a domestic or foreign origin (e.g., the high Chinese demand for Mozambique’s timber), so it’s important to derive proxies for both. While again still rather preliminary, I looked at the domestic CO2-e emissions for those same African countries mentioned above, as well as Hansen and colleagues’ data on deforestation from 2000-2014.

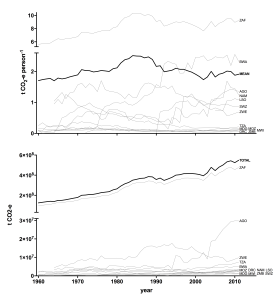

Per capita (top) and total (bottom) emissions for southern African countries

While overall average per capita CO2-e emissions have been roughly invariant since the 1960s (at about 2 t CO2-e person-1), the rise in population and South Africa’s industrialisation in particular means that total emissions have been rising steadily since then.

Deforestation has also been rather high, especially in countries with a lot of forest to lose (like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mozambique, Madagascar, Angola, and Tanzania). In fact, Mozambique itself lost 3% of its total surface area in forests from 2000-2014 (some 20,000 km2), representing a net loss of 2.5% over this period. The Democratic Republic of Congo fared terribly as well, with a total loss of a whopping 60,000 km2 (2% of total land area).

So my message is simple. While the exact form of rising pressures on African wildlife (and mammals in particular) will depend on so many elements associated with patterns of urbanisation, agriculture, migration and overseas demand, there is no question at all that biodiversity there will be increasingly susceptible to perturbations originating from us. How we avoid the worst of the obligatory declines is the challenge now.