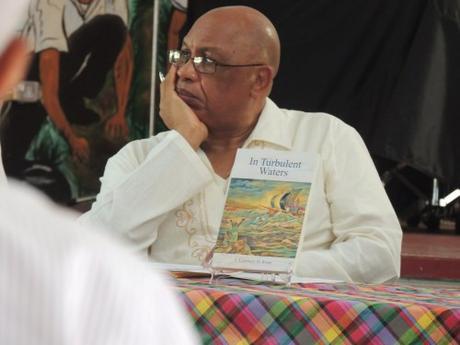

Fr. Lambert St. Rose

Fr. Lambert St. Rose is one of the best-known Roman Catholic clerics in St. Lucia. Whenever he happens to be speaking from the pulpit or using his literary skills to give voice to his thoughts and feelings, he never fails to command attention. Esteemed and admired by many, he has also been a source of unease and even trepidation to some, both in and out of the Church.

In this dark era of economic uncertainties and crass materialism, when pastors frequently resort to feel-good sermons about self esteem and coping with personal and financial problems in ways that appeal to the emotions but do little to challenge souls to seek renewal and conversion, Lambert St. Rose’s contempt for appeasement and his refusal to kowtow to political correctness have long made him an outlier and somewhat of an enigma.

St. Lucia’s Catholics know better than to turn to him for church services consisting of staid formalities, with the congregation listening in gloomy silence to treatises on religious dogma. Inspired, no doubt by the cruel realities of the post-colonial Caribbean, he’s more likely to focus on showing his flock the path that would lead to spiritual redemption, while at the same time urging them not to condone political and societal corruption, and to take a stand against the oppression of the poor.

In his poet-writer persona, he’s no different. In 2011 he launched his debut poetry collection, Helen and Her Sister Haiti, in which he pays homage to his homeland, St Lucia and its exquisite natural beauty, even as he bemoans the crippling socioeconomic struggles of its people, many of which mirror the woes of sister-island, Haiti. He also denounces the political corruption and social injustices still plaguing the Caribbean more than two centuries after Emancipation. He characterises it as a ‘new form of slavery’ that is creeping back into the islands, and tries to give hope to the region’s downtrodden.

Now he has turned the heat up a notch with his latest book, In Turbulent Waters. It was unveiled November last year at a grand book launch held at the St. Mary’s College auditorium, and was very well attended. St. Lucian poet and winner of the 2015 OCM Bocas Prize in the poetry category, Vladimir Lucien delivered the feature address. A work of fiction, it revolves around the life and priestly vocation of Fr. James Laport, a young Catholic cleric from the fictional Helen Island, and the travails and blistering rite of passage that he’s forced to endure as he pursues his calling.

Like most youths growing up in Helen Island during the earlier part of the 20th century through to the early 70s – a time when ‘television was just a name’ – James Laport was born to a working-class family on the outskirts of the capital, Félicitéville. Growing up, he and his siblings were often regaled with frightening tales of black magic, witches and sorcerers, and stories about Tim Tim, Konpè Lapen, Konpè Tig, Bèf Louwa, ghosts, spirits, lajables and jan gajé, and men transforming into creatures equipped with extended genitals and entering people’s homes through keyholes to sexually molest women – all of it gleefully recounted to them by their parents and the elders of the community. Known in the Kwéyòl vernacular as listwa (story time), those sessions were hugely popular in an age when storytelling was ‘quite instrumental as family entertainment’ and a form of ‘encultration of the youth,’ and everyone was always ‘gripped in the claws of the storyteller.’

Unlike his father who was a ‘seasonal Catholic’ and occasional churchgoer most of his adult life, James Laport’s mother was a Poto Légliz (ardent churchgoer) and presumably had some influence in his aspirations to join the priesthood. Throughout his teenage years and early adulthood, up until his assignment to the Archangel Parish Church in Geckoville to prepare him for his ordination, James had always dismissed stories about black magic, ghosts and spirits as mere ‘phantoms of creative imaginations and mischievous minds,’ notwithstanding they often gave him the creeps as a child.

Fresh out of university and refined by his interaction with highly cultured intellectuals whose minds had been reformed by Western influence, and who behaved as if their ‘new found-culture was superior to that of the people who held on to the old myths and legends,’ Fr. Laport soon discovers, to his dismay, that those legends are still very much alive in the hearts of the faithful and many view them almost as metaphors for the ‘high occult sciences of the day.’

Soon after taking up his clerical duties as an associate pastor, James Laport has his first rude awakening when a woman bearing her infant in her arms, approaches him and begs him to help her child who is seeing spirits. She’s the first of a string of parishioners who turn up at his doorstep in quick succession, pleading with him to deliver them and their family members from all manner of demon possession, ghostly hauntings, obeah spells, ritual murders, occult attacks, Black Masses and human sacrifices.

In one of the more poignant episodes, prior to the commencement of a ‘Praise and Worship’ celebration held at the town’s playing field, Fr. Laport catches sight of something unusual as he approaches the gathering – a pig standing on its hind legs. A terrified altar server standing next to him blurts out that it’s a pig with a human body. Fr. Laport quickly sprinkles the gathering with holy water and immediately the being makes a panicked dash to try and avoid the water. Several bystanders point to a woman in the crowd and they begin shouting in panic, “Mi an kochon moun anpami nou wi.” (There’s a human pig among us). At that point, the woman grunts and some people in the crowd recognize her. They plead with Fr. Laport to take her into the church and pray over her.

As the story progresses, more parishioners seek Fr. Laport’s help in exorcising demonic spirits and freeing people from occult spells and Satanic attacks. With each incident, the ordeal grows more terrifying and bizarre. Fr. Laport becomes so overwhelmed a visiting priest is forced to come to his aid by teaching both him and his fellow cleric, Fr. Fallon the principles of exorcism.

Worst of all, it’s now impossible for him to ignore the reality that within the very walls of the churches, and in the wider community, there are individuals who have made a conscious decision to explore the latent potentialities of the occult with the sole purpose of securing personal gain or to inflict pain and suffering on those whom they despise or consider their enemies. They are two-faced characters who live duplicitous lives and comfortably straddle two worlds – the sacred and the profane. The gravity of the situation and the catastrophic consequences for the society are driven home to him when a local politician confesses to him, ‘Father, when it comes to elections, if one has to sleep with the devil to win, that’s what it takes. ‘

As pleas for deliverance continue to pour in from the various parishes to which Fr. Laport is assigned, the full implications of religious assimilation and syncretism become apparent; likewise the community’s susceptibility to those with dark and malicious intentions. The pervasive influence of occultism also becomes disconcertingly obvious, and all this takes a heavy toll on the overwhelmed cleric. Like the Biblical prophet, Jonah he begins to despair and over and over again he feels the urge to escape from it all and ‘flee from the presence of the Lord.’ But each time his faith in Christ lifts him up and stiffens his resolve, and he proceeds to confront the hidden and traumatic realities of daily life in Helen Island and further afield on a neighbouring island, not just to help the members of his flock cope with the horror of it all but also for the sake of preserving his own sanity.

A section of the audience at the book launch

Although In Turbulent Waters is presented as a work of fiction, Fr. St. Rose makes it clear in his introduction that the use of fictional names and places is ‘for the sole purpose of protecting the identities of persons.’ He adds: ‘Many [of them] have passed from this world’ and ‘those who dare to make their exit, live in perpetual torment with the threat of death hovering over their heads.” Some others, he says, still ‘linger and squirm in their misery because of their stubborn reluctance to embrace conversion,” while others continue to dabble in the dark arts and ‘recruit members into the cults.’

The obvious inference from that is clear; while the characters and setting may be fictional, their life experiences are anything but, including that of James Laport. Those who know Lambert St. Rose well would find it hard not to see in James La Port a reflection of Fr. St Rose’s own life experiences while serving in St. Lucia and other parts of the Caribbean.

He says his aim in writing the book is to show the reality and gravity of ‘cultic activities’ and the debilitating impact they are having on people’s lives and on the communities. ‘Baphomet wields a heavy hand in many national decisions, supported and encouraged by those considered as highly civilized persons,’ he adds.

The writing style he employs does not strive to conform to the conventional literary form and structure. Instead, he creates a series of vignettes and uses a format and cadence that are more akin to St. Lucia’s Kwéyòl ‘Listwa’ tradition, sometimes reminiscent of the oral storytelling device popularly known as ‘Kwik-Kwak.’ It is also spiced up with copious flashes of wit and humor.

The preface was written by board chair of St. Lucia Save the Children Fund, Loyala Devaux. As she correctly notes, Fr. Lambert St. Rose has tread ‘where many fear to go.’ She’s also spot on in anticipating that many of the book’s readers are likely to adopt the view that it’s merely ‘imagination, fabrication and speculations.’ In Turbulent Waters conjures a fearful, two-dimensional world where the good and virtuous live cheek by jowl with the evil and the depraved, and often it’s hard to distinguish one dimension from the other. At the very least, it requires extreme suspension of disbelief.

Nonetheless, there’s no denying the fact that scientific research in quantum dynamics, and shifting assumptions among scientists, not to mention recent discoveries in astrophysics and paranormal phenomena (i.e. the connection between Dark Energy, black holes and wormholes and phenomena such as telepathy, near death encounters (NDEs), ghosts, and astrology) are leading more and more scientific experts to conclude that consciousness exists outside of the constraints of time and space (and beyond the normal sensory spectrums of most humans) and is capable of manifesting anywhere. There is also growing consensus among scientific thinkers that thoughts and intentions – whether beneficent or malevolent – as well as prayer and other forms of conscious intelligence can directly influence our physical material world.

What’s more, the various phenomena vividly depicted in Fr. St. Rose’s novel – the convocation of spirits, the existence of hybrid creatures (part human and part beast), the materialisation of anomalous cryptids capable of moving in and out of human reality, the prevalence of incubi and succubi (spirit beings capable of taking on human form and who, according to ancient legendary traditions, lie upon sleepers, especially women, in order to engage in sexual intercourse with them) and the ability of these intelligences to coexist with and affect humans negatively or positively were all considered fact in ancient times by practically every nation and culture under the sun. They have also been affirmed by many of the Biblical writers and some of the Deuterocanonical, apocryphal and Judaic sectarian texts.

Moreover, thanks to the availability of advanced 21st century technologies, numerous incidents of paranormal phenomena and altered states of consciousness are being investigated and reported on by researchers all around the globe, despite the fact that they receive little to no attention from the global mainstream media.

Lambert St. Rose’s academic and theological credentials are solid. He’s a graduate of the Regional Seminary of St. John Vianney in Trinidad, he holds a Masters in Theological Studies (MThs) from St. Norbert’s College, De Pere Wisconsin, with a year’s stint at Catholic Theological Union (CTU) in Chicago. He co-authored Theology in the Caribbean (1994) and Into the Deep, Towards a Caribbean Theology (1995). But make no mistake – In Turbulent Waters doesn’t come across as the cerebral indulgence of some armchair intellectual. It is a gripping tale told with raw and disarming candour and in a matter-of-fact way that draws you in and keeps you hooked from beginning to end.

Fr. St. Rose no longer manages a parish like he used to due to ill health. But judging by his new book, he’s not about to let sleeping dogs lie nor does it look like he intends to ease up on those he berates as ‘vagabonds of culture and squanderers of tradition,’ men and women who, according to him, have “radically departed from the objectives of Listwa Time: the perpetuation of holistic genuine human growth and development, and the avoidance of evil at all cost.”

In Turbulent Waters is available online at Amazon.com, Barnes & Nobel and other major online bookstores.

Copies are available at the following places in St. Lucia: The Chancery Offices, Vigie, The Folk Research Centre; St. Augustine Bookshop, and Bezata Gifts & Graces Bookshop in Castries