In her review of Elizabeth Kolbert's The Sixth Extinction (NY: Henry Holt, 2014), Louise Rubacky notes that Kolbert's thesis — that humankind has precipitated the sixth planet-wide mass extinction of species, and this has already begun — warns of dire consequences when we "break evolutionary chains." Every species now disappearing had its niche in the complex, interwoven, delicate ecology that sustains the whole planet. And the loss of even a single species threatens to unbalance a web of relationships necessary to sustain life as we have come to know it on this planet.

And so Rubacky sums up Kolbert's thesis as follows:

We are the one species that seems trapped in a vortex of global destruction, and we can’t find an exit strategy. How much time we have left to react to reality, and accept the connection between us and them-with-the-smaller-brains, is unclear. But the story is pointing toward an unhappy ending. And it will be dramatic.

On the same day that I read Rubacky's review at Truthdig, I find Sara Gates reporting at Huffington Post, "In recent years, the planet has seen the loss of hundreds of species of animals, and according to a new analysis from an international team, the planet may be in the early days of its sixth mass-extinction event." And then she goes on to note,

So what does this mean for the planet?

There may be unforeseen consequences, aside from the possible extinction of threatened species.

"We tend to think about extinction as loss of a species from the face of Earth, and that's very important, but there's a loss of critical ecosystem functioning in which animals play a central role that we need to pay attention to as well," [Rodolfo] Dirzo [of Stamford University's biology department] said in a statement.

Poet (and essayist) Mary Oliver tells us that she believes everything has a soul (Blue Pastures [San Diego: Harcourt Brace, 1995], p. 63). She also reminds us that the globe on which we live behaves thusly:

Opulent and ornate world, because of its root, and its axis, and its ocean bed, it swings through the universe quietly and certainly. It is: fun, and familiar, and healthful, and unbelievably refreshing, and lovely. And it is the theater of the spiritual; it is the multiform utterly obedient to a mystery (Long Life [Cambridge, MA: Da Capo, 2004], p. 90).

The entire planet is "the multiform utterly obedient to a mystery." The loss of even a tiny portion of the manifold forms sustaining the whole unravels a mystery at the heart of it all — and may well unravel life for all of us who are sustained by the nurturing mystery from which the web of life spins forth.

Poet (and essayist and novelist and farmer) Wendell Berry tells us that nature itself is never "pure," as we imagine when we juxtapose the idea of wilderness to the notion of cultivated land. Even apart from human interference, Berry points out, nature is a construct, a balance of constantly shifting relationships (Home Economics [San Francisco: North Point, 1987]). Touch one single strand in the web of relationships, and the entire web quivers in response.

We have refused to listen to our poets to our great peril, as our scientists now warn us. If, as Edward Lorenz has maintained, the beating of a single butterfly's wings over there may affect the formation (or prevention) of tornadoes here, then where will we be, I ask myself, when that butterfly's wings are stilled? When all butterfly wings cease to beat?

We have not thought through the condition of our lives in this world nearly ponderously enough, have we? There has been so much money to make, after all. Who has time to think? And so many goods to consume before it's all over and done with, as well . . . .

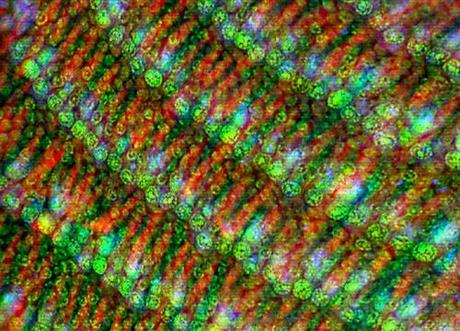

The graphic, a butterfly wing viewed under microscope, is from this amazing gallery of butterfly wings viewed through a microscope at Imgarcade.