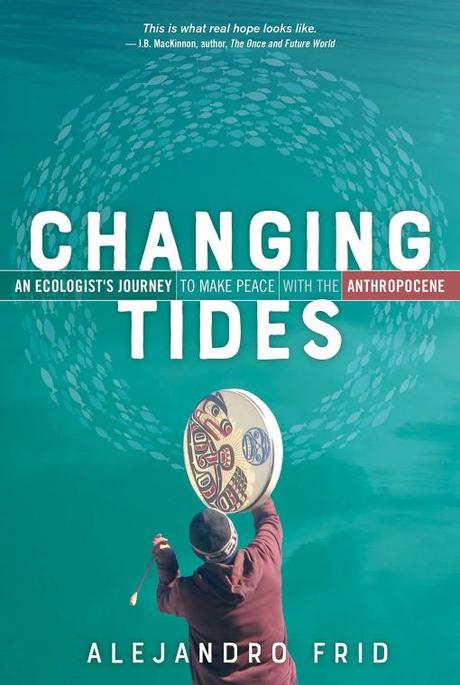

An excerpt from Alejandro Frid‘s new book, Changing Tides: An Ecologist’s Journey to Make Peace with the Anthropocene (published first in Sierra, with photos courtesy of New Society Publishers)

An excerpt from Alejandro Frid‘s new book, Changing Tides: An Ecologist’s Journey to Make Peace with the Anthropocene (published first in Sierra, with photos courtesy of New Society Publishers)

—

The birth of my daughter, in 2004, thrust upon me a dual task: to be scientifically realistic about all the difficult changes that are here to stay, while staying humanly optimistic about the better things that we still have.

By the time my daughter turned eleven, I had jettisoned my nostalgia for the Earth I was born into in the mid-196os—a planet that, of course, was an ecological shadow of Earth 100 years before, which in turn was an ecological shadow of an earlier Earth. The pragmatist in me had embraced the Anthropocene, in which humans dominate all biophysical processes, and I ended up feeling genuinely good about some of the possible futures in which my daughter’s generation might grow old.

It was a choice to engage in a tough situation. An acknowledgement of rapid and uninvited change. A reaffirmed commitment to everything I have learned, and continue to learn, as an ecologist working with Indigenous people on marine conservation. Fundamental to this perspective is the notion of resilience: the ability of someone or something—a culture, an ecosystem, an economy, a person—to absorb shocks yet still maintain their essence.

But what is essence?

Ecologists have one kind of answer to this question. In the early 1970s, Buzz Holling—a highly influential ecologist and, I like to boast, my academic grandparent (Buzz supervised the dissertation of another influential ecologist, Larry Dill, who in turn supervised my dissertation)—formalized the concept of ecological resilience into the language of Western science. The notion was already well understood in the traditional knowledge of many Indigenous cultures, yet Buzz pioneered its mathematical expression and was the first to acknowledge its implications for how industrialized societies exploit ecosystems. Generating beautiful curves, concentric circles and spirals, he described how external forces disturb ecosystems, forests burn or are logged, wetlands flood or dry out, exotic species infiltrate food webs. By itself, that was old news. But Buzz went further by explaining how, despite these disturbances, ecosystems could maintain their essential structure and function, as long as certain interactions and processes endured. For a forest, that might mean being burnt to a crisp yet not losing its ability to regenerate over time into a vertical woody structure resembling that which existed before.

History, however, is unlikely to repeat itself exactly. Extinctions, invasive species, and climate change might preclude the regenerating forest from maturing into the exact same combination of species or age structure that it held in the past. Yet a shift in species composition does not necessarily change the essence of an ecosystem. In the case of the forest, this essence includes slugs or other decomposers breaking down plant matter so that the nutrients are incorporated back into the soil; trees providing structures for lichens, mosses, ferns and cavity nesters; predators like wolves and cougars keeping herbivores like deer from overbrowsing plants; high winds breaking branches and knocking down individual trees, thus creating gaps in the canopy that allow light to pour in and support a vibrant understory.

The idea of resilience, and its explicit acknowledgment of change, is very different from the more old-fashioned (and unrealistic) view of Western conservation, in which ecosystems are intended to stay as they were when we first became aware of them. We must not, however, misconstrue resilience thinking as license to disturb everything in the name of human business. Crossing a threshold of disturbance will hurl ecosystems into something fundamentally different, from which they are unlikely to come back—what ecologists call an alternative stable state—such as a forest pushed beyond the possibility of regeneration becoming a biologically depauperate shrubland. More resilient ecosystems can take in more shocks without being thrown into an alternative stable state.

These ecological notions helped me make my peace with the Anthropocene. They gave me tools for distinguishing human-caused changes that I can live with (those that do not reduce resilience) from those that I fiercely oppose (those that, alone or in combination with other stressors, erode resilience). Effectively, this means managing humans so that whichever disturbances we can control—how much we log, how much we fish, how much carbon dioxide we release into the atmosphere—do not create the perfect storms that jolt ecosystems into alternative stable states. And when alternative stable states do become inevitable, as they certainly will in our changing climate, resilience thinking might help us steer towards the ones that are more benign—something akin to anticipating engine failure in a plane yet being ready to make as smooth a landing as possible.

I constantly think about the parallels between ecological resilience and Indigenous cultural resilience. Part of it is intellectual curiosity. But mostly, I am just trying to hand my daughter’s generation a better world.

Indigenous cultures that derive their resources and world views from the myriad wild species that they hunt, fish, gather, and tend have existed for thousands of years. Over time, as resource managers, they have developed intentional and socially complex practices that epitomize sustainability. Some of these cultures were crushed by colonization. Yet many, despite immense historical challenges, endure: they maintain their essence while adapting to a rapidly changing world. Their experiences are not devoid of severe loss, yet they also embody resistance, intentionality, self-identity, and resilience. Perhaps they provide a model for how we might navigate the irrevocable changes we have unleashed upon our planet and help us steer towards a more benign Anthropocene.

Through my day job, I regularly spend time with some of the Indigenous leaders who are helping their communities emerge from the dark horrors of colonization, revitalizing their cultures into something that is both modern and grounded in tradition. I have stacks of handwritten journals from my time in villages and in the field, and those journals, I believe, hold key insights into the issues that I seek to understand.

Yet those same journals also throw hard questions at me.

Human impact on the planet precedes industrial civilization by a long shot. The collective psyche of agricultural civilization began to break apart many ecosystems about 10,000 years ago, triggering a barrage of extinctions, both biological and cultural, as large settlements depending on a very small number of cultivated and farm-raised species began to displace complex ecosystems and the peoples who depended on them. There also exists little doubt that, thousands of years before the first harvest of domesticated grains ever occurred, the collective psyche of very early hunter-gatherers, as they first arrived on continents previously uninhabited by humans, contributed to massive extinctions: notably in Australia 55,000 to 42,000 years ago and in the Americas 16,000 to 14,000 years ago. A changing climate likely made many species more vulnerable to overhunting, but that does not diminish the likelihood that, in the absence of humans, fewer extinctions would have occurred.

But no matter how you look at it, as far as destruction goes, industrial civilization has far outperformed preindustrial agriculturists and prehistoric hunter-gatherers. Just in the past century, we have raised the Earth’s average temperature by 1°C, and we are still cranking up the heat, propelling the planet into a new geologic era that already has caused many species extinctions and is altering the future of all ecosystems for millennia to come. The scales of ecological disruptions caused by preindustrial agriculturists and prehistoric hunter-gatherers were child’s play by comparison.

Recognizing the collateral damage of the Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions has been straightforward for me. The evidence for these historical landmarks is crystal clear. And maybe I want to believe that these have been our species’ teenage stages, when the societal equivalent of an underdeveloped neocortex has kept us from fully understanding the consequences of our actions.

But it was more difficult for me to reconcile the deep past, when prehistoric hunter-gatherers did cause many extinctions, with what the human capacity to conserve might actually be. Are humans really that innately destructive?

Maybe, maybe not.

An alternative view is that humans have been “deadliest” only during specific historical periods or when belonging to specific cultures. That is, prehistoric hunters wiping out entire ungulate herds, agriculturists running amok, and climate-altering industrialists represent incomplete windows into the ways many human cultures have carried, and still carry themselves, in the world.

Alternative interpretations of human history give greater emphasis, and credence, to the world views of cultures that connect strongly to the specific places where they originated and still exist, and that have developed reciprocal relationships with the native species that share those places. My short version of that reinterpretation is as follows:

After some centuries of raising ecological havoc in their “new” continents, hunter-gatherers settled down. The land ceased to be an expanding frontier and became home, the place where we humans can find our medicines, our songs, our stories—the reasons why we exist at all. Once committed to staying in place until the end of time, they became invested in their descendants. They continued to hunt, fish, and gather plants, yet they stopped killing and consuming resources anywhere and anytime. Instead, they began to actively manage themselves, curtailing waste and tending the landscape in ways that promote the diversity of native species. Had they not changed their ways, they, too, would have become extinct. Once rooted, many cultures became visionary in their long-term resource management strategies—identifying sustainable rates of harvest for different species and transmitting this understanding intergenerationally—to the point that human-caused extinctions ceased in their continents until the arrival of Europeans.

Granted, the Indigenous picture is not uniform. A mere few centuries ago some societies that developed in the new continents caused their own ecological havoc that led to social collapse. But these collapses involved agricultural societies, such as the Maya and Anasazi of Central and North America, who had lesser connections to the broader diversity of species and instead simplified ecosystems in ways that favored a few domesticated plants and animals.

In contrast, cultures that remained connected to the larger variety of native plants, animals and other organisms for their fundamental economics and spirituality—underlying their connections to biodiversity with reciprocity and respect—continued to thrive, and likely would have continued to do so had they not been severely disrupted by European colonization over the last couple centuries. As I will elaborate over the course of this book, these cultures are still here, revitalizing themselves and increasing their political influence in some countries, such as Canada. Even so, their legacy and modern influence remains, so far, dangerously underappreciated. To ignore the accomplishments of cultures whose very existence depends on reciprocal and respectful relationships between themselves and their ecosystems is to shortchange the human potential

Sixty-six million years ago a huge asteroid collided with Earth. The shock unleashed earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions, obliterating three-quarters of animal species on land and sea. I like to think of the emergence of some human cultures that crystalized much later, only within the last 14,000 years or so, as the inverse of that event. Wherever people ceased to live like roving bandits, sequentially depleting area after area, and instead became inherent to specific places and to their functioning ecosystems, biodiversity thrived and persisted.

DuqvaisJa (William Housty), a Heiltsuk hereditary chief dedicated to integrating the traditional knowledge of his people with scientific methods for resource management and conservation, points out that, according to customary laws known as Gvi’ilas, “Heiltsuk have been present in traditional territory since time began and will be present until time ends.” This belief, which is shared by all First Nations with whom I have spent time in Canada—both coastal and inland—arguably is the most powerful conservation tool imaginable. The moment you believe—in your spirit, your gut, your whole being—that the surrounding lands and waters are where your people have lived “since time began” and that those very same places are where your people will stay “until time ends,” a cascade of commitments and responsibilities begins to flow.

This cascade, DuqvaisJa writes in reference to Gvi’ilas, includes “responsibility over traditional territory as much as over immediate home,” which entails that, “out of respect and understanding, certain areas should be off-limits to some, or all, human activities.” Further, “The right to use a river system [or any other part of the land or sea] comes with the responsibility to maintain [it] in its natural or ecological entirety.” And critically, the focus of resource management decisions “should be on what is left behind, not what is taken.”