Mike Bayly looks back at fondness at a sadly departed member of our younger years.

For all the perceived benefit modern technology brings, it has the effect of dehumanising human interaction. Whilst innovations such as smartphones, Skype and social networking sites have made global communications more accessible and cost effective, there is little doubt they have subverted the principles of human relationships. Text messaging has negated the need to actually pick up a phone and speak to someone. Email has rendered letter writing obsolete to the point of being archaic. Facebook allows a hundred people you barely know to wish you happy birthday without having a single card on the mantelpiece to commemorate the fact. At times, it even effects the group dynamic; going out with friends and spending half of the evening buried in your iPhone has become so commonplace as to be practically de rigeur.

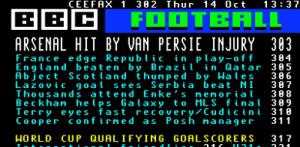

In truth, Ceefax had become the distant relation whom we never visit. Once an integral part of people’s lives, it succumbed to the ubiquity of the internet, and for the last decade or so has been sat alone in a forgotten corner of our consciousness waiting to die. For football fans, Ceefax has an almost mythological status. Many of its epitaphs relate to the football service, with ‘page 302’ assuming Old Testament proportions of deity. For years, Ceefax was the de facto method of keeping up to date with how your team was doing, unless you were part of the world’s financial elite who could afford to dial up Clubcall on a regular basis. The premise, particularly on match days, was simple. Fixtures would be laid out on a screen, and load across several pages. This would usually amount to three per division, though real aficionados could always tell when a glut of goals went in as the pages would extend to four, five or even six to accommodate the goal scorer’s details. The rotating nature of the pages added to the tension. At times, their cycle would be infuriating slow, as if the technician in charge of content had a conspiracy against your team.

On occasion where your club was involved in the only fixture of the night, it was particularly nerve shredding, as pages only tended to update if there was significant action. In these occurrences, the ‘reload’ button would be tested to full capacity. Watching the page numbers scroll through the top left hand corner of the TV screen generated excited trepidation, like a heroin addict pacing up and down before a drop off. This may seem rather specious, but anecdotal evidence suggests otherwise. Frank Skinner once recalled how he spent the evening in a hotel room on tour watching the West Brom result come in over Ceefax. The tension became so bad that he started walking out of the room, or standing at an angle whereby he could only just glimpse the TV. At times he even covered the screen with a pillow. To the layperson, it might sound comically obsessive, but to thousands of supporters across the county it was a self imposed and well rehearsed purgatory.

Whilst some facets of Ceefax slavery may seem decidedly insular, the service could also be a great social leveller. For all the lamenting of its passing, few paid deference to its ability to congregate groups of people in the most unlikely of places. On any given Saturday over the last thirty years, a mainstay of British football culture was the sight of fans stood in Dixons or John Lewis watching the results service come in over Ceefax. The sheer number of TVs all showing the same synchronous output gave proceedings a distinctly Orwellian hue, set against a duplicitous backdrop that you were “just browsing”. Whilst there may have been some punters genuinely interested in purchasing the latest widescreen Matsui, most were there explicitly to check the latest scores. Dixons was often a refuge for bored men who had tired of clothes shopping with their partners. Males were never designed to sit outside the changing rooms in Topshop, affecting jaded smiles of approval at the remorseless procession of clothing their women wished to try on. Escaping to Dixons to watch Ceefax was the evolutionary equivalent of Neanderthal man leaving the cave to club a Sabre-toothed Tiger.

Where Ceefax really came into its own though was at 4.45pm on a Saturday, creating the curious but reassuring sight of men huddled round the windows of electrical retailers watching the final scores come in. Sometimes groups could reach double figures, as fans peered through the glass watching the results filter in, often with Steve Ryder as muted company on BBC One’s Grandstand. Some of my happiest memories have been spent standing outside Radio Rentals with a crowd of strangers waiting in anticipation for my team’s scoreline to appear. The lone shout of triumph or groan of resignation from an eclectic supporter base only added to the atmosphere, until everyone slowly drifted away into the ambient twilight of a largely deserted precinct.

I will raise a glass to Ceefax when it finally withdraws across the country in October of this year. And then I will tell a thousand strangers on Twitter why it will always hold a special place in my heart.