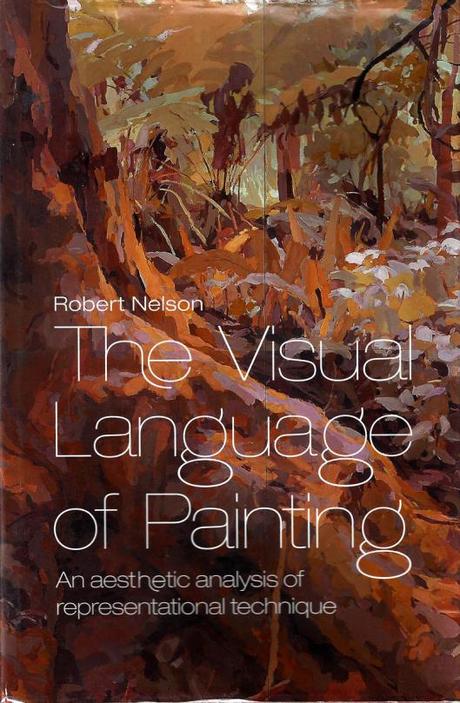

I had the excellent good fortune to be gifted this well-considered, eloquently written book which I am currently reading for the second time—

Robert Nelson’s The Visual Language of Painting: An aesthetic analysis of representational technique.* Nelson, who works in Monash University’s Faculty of Art and Design in Melbourne, embarks on a project of writing about painting in a way directly connected with, though not wholly confined to, technique. Where art historians have gone ‘into a heady reverential transport which strives—fatefully, I think—to clinch sentiments exceeding comprehension,’ painters—‘the people who know it best’—generally fail to explain that mute something and rely on visual language rather than verbal language (p. 1). Nelson, himself a painter, suggests that rather than insisting that painting is a purely sensual experience or that it forms a text through symbolism, painting itself may be ‘a vehicle for discourse’ (p. 10). He elaborates (pp. 27-28):

I would like to see a philosophy of technique which positions technique as the necessary correlate of poetic vision and the basis of visual language, a philosophy which is non-instrumental and anti-mechanistic. I would like to cultivate a discourse which deals with the motivation, the aesthetic benefits, the almost physiological processes of perception, but also the wilful staging, the theatricality of expressing what happens in the mind, the eye and the hand. … The project, if it could be pursued as I hope to demonstrate, would bring studio technique into the heartland of scholarship in the humanities.

His firm belief in the interrelation between thought and practice resonates deeply with me, as I have cobbled together an education by pursuing art through traditional atelier-based studies and pursuing ideas through academic studies in philosophy. If we could only talk about painting, its cadences and phrasing, its potency when well-executed, divorced from meaningless statements about transcendence and manifestations.

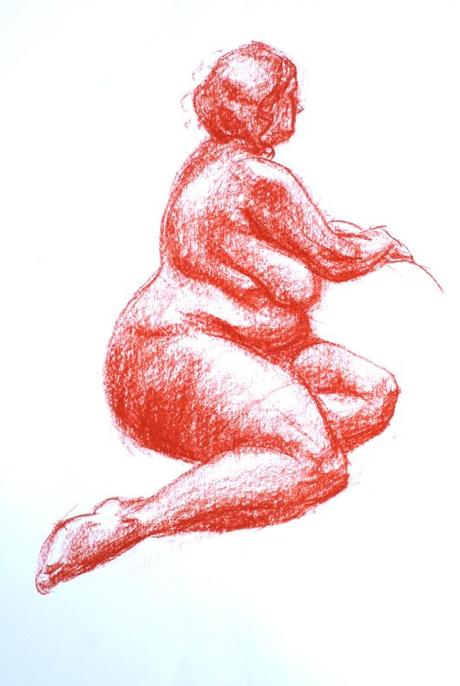

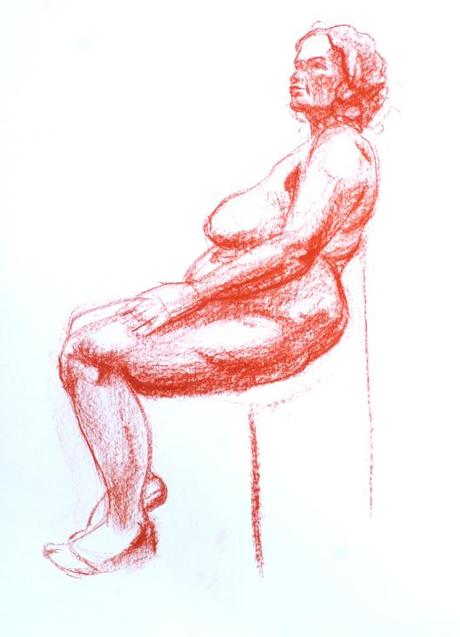

Recent life drawings in Conté crayon

The chapter on drawing and perception is a particular favorite of mine. Drawing holds a special place in my heart. The precision of drawing, the intimacy of exploring a subject, the sensitivity of lines that investigate the flow and movement and the form, the gradual build-up of tones, the plasticity of the image and the things it reveals to your slowed, deliberate gaze is all a little bit intoxicating. Nelson (p. 52) esteems drawing highly in a modern world that seems to have lost interest in good draughtsmanship: ‘Drawing was (and still is) the tool by which sophisticated societies get things done,’ he argues. ‘Drawing in the sense of design has authority. It determines what is to be done. It is the organ by which instructions are passed down the line of command.’ He refers to this sort of drawing—the kind that precedes construction or manufacture, as synthetic drawing. It allows us to bring new constructs into existence through our ability to imagine and to accurately notate our intentions to change our physical environment.

He equally esteems what he refers to as analytic drawing: the kind that investigates a subject, when one draws from life. He captures the excitement and challenge of drawing from life when he says, ‘There are psychological forces that lead the eye through space. A plethora of mutual directions vibrates between hand and eye as the brain figures out a reasonable and sometimes inspired compromise between what the eye sees and the hand can express’ (p. 82). But beyond this, he talks about the extreme importance such analytic drawing had in a world without easy mechanical or digital reproductions. Drawing was then (and still can be, for those dedicated enough to sit down and give time and thought to it) ‘almost … a way of seeing’ for artists who depended on it every day (p. 61). This captures something distinct about drawing. While it can produce visual records, it is not necessarily the product, the drawing-as-noun, that is of the most significance. Rather, the drawing-as-verb, the process, is a particular kind of engagement that the artist has with the physical world. The drawing artist is afforded a special kind of appreciation of the world, because her seeing is active and bound up in her response, not simply in the receiving of light on the retinas. Nelson (p. 61) asserts: ‘The level of scrutiny that drawing affords is hard to match, and the comprehension that it yields cannot easily be replaced.’

When we recently held a book club discussion on Annigoni’s defence of drawing, the question came up of what makes a good drawing? What entitles us to make such a judgement, and on what authority do we distinguish between a pleasing drawing and a good one? While open to many styles and interpretations of the physical world, there is undeniably something that makes a drawing good, and there are a great many drawings of questionable quality out there. It is not simply a matter of realism, or of beauty. A fluent line doesn’t always cut it. What tends to set good drawing apart is the evidence of this scrutiny, of a grappling with the information received through the senses, of an application of knowledge about a subject—whether anatomy, or depth, or form, or light.

Nelson (p. 46) approaches the discussion of drawing through the question: is it well drawn? His conclusion is that a well-drawn drawing shows evidence of intelligence. Simple mimicry of outlines does not convey understanding. Direct aping of tones does not demonstrate an investigation of objects receding in space or reflecting light in ways consistent with physics—or of a true appreciation of the configuration of a knee, built of specific and descriptive lumpy bits. We must be honest: are we drawing to fool an ignorant audience, or are we drawing to actively engage with the physical world, audience be damned? Drawing thus becomes firstly a very personal thing, bound up with the act of seeing, and the artefact appreciated by others is but a by-product—not created for them.

When drawing becomes a function of the person drawing, not a thing for show, it becomes an intellectual exploration and an argument—a personal conviction. Nelson (p. 54) says it ‘manifests your will to possess intellectually.’ When an artist owns what he sees through the act of drawing, he asserts an authority through the marks he makes. This brings Nelson to the conclusion that ‘the best drawings are those which have a look of commitment about them.’ And, futher, ‘we are justified in rating as lesser the drawing which resiles from such commitment. We may be disappointed that the perception or feeling is not accorded such dignity; too little ceremony has been bestowed upon the subjective; the intuitive has not been promoted to the institutional. Drawing can do this’ (p. 55).

Drawing is a means of responding intelligently and with dignity to what we see. It isn’t the poor cousin of painting; nor does its relevance stem only from its role in design. As Annigoni himself asserted, ‘The truth is that the deformations of contemporary painters very seldom arise from stylistic requirements forced on the artist by his vision. They merely spring from a confused desire to be controversial, a surprising indifference to the human being and, one might add, a lukewarm commitment to life itself. The result is absolute indifference to form, lack of proper preparation and a heavy dose of sheer ineptitude. This last quality has today, it seems, acquired full rights of citizenship in the realm of art.’

* Nelson, Robert. 2010. The Visual Language of Painting: An aesthetic analysis of representational technique. Australian Scholarly Publishing: Melbourne.