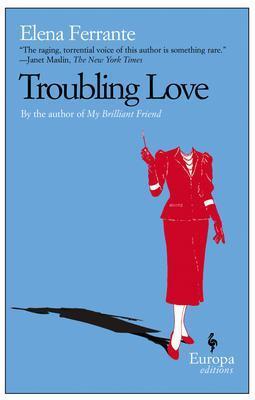

Troubling Love. by Elena Ferrante and translated by Ann Goldstein

This’ll be a short review, because unfortunately even after only a month or so I can already remember almost nothing about Troubling Love. Perhaps that’s the only review I need give it.

Ferrante though has been one of the big discoveries of the past year for a lot of readers. Joanna Walsh has championed her in the Guardian, and many blogs I follow have raved about her. I plan to give her another try, but I’d be very interested in hearing in the comments from anyone else who’s read this one or has thoughts on Ferrante more generally.

The novel opens with the narrator, Delia, remembering the death of Amalia, her mother. Amalia had been coming to visit but had never arrived. Later her body washed ashore; she had committed suicide on Delia’s birthday.

Delia’s relationship with Amalia had been a tangled one, as is true for many people with their parents. I loved this description of Delia tidying after each of Amalia’s visits:

I went through the rooms rearranging according to my taste everything she had arranged according to hers. I put the saltshaker back on the shelf where I had kept it for years, I restored the detergent to the place that had always seemed to me convenient, I made a mess of the order she had brought to my drawers, I re-created chaos in the room where I worked.

Before she died, Amalia made a series of incoherent calls to Delia. She said she was being held by a man; she laughed; she rattled off a string of obscenities (something characters do a lot in this book). When she was found she was naked except for a new and expensive bra, quite at odds with her usual clothes.

Amalia’s death makes little sense to Delia, not so much the fact of it as the facts around it. Why did her mother get off the train early? Who was the man she referred to? What happened to her normal clothes and a suitcase she had with her when she set off? Why did she have the high-end lingerie?

More strangeness soon emerges. Delia learns that her mother had been seeing someone; her neighbor says she was happy. Years before Delia’s father had been obsessed with the idea of Amalia’s infidelity. He had stopped her from going out and from dressing up. Was she now making up for lost time?

An elegant old man appears at Amalia’s apartment. He had been at the funeral too, where he had reeled off a litany of obscenities (seriously, this happens a lot in the book, usually with variations of that phrase to describe it). He has the missing suitcase, and trades it with Delia in return for a bag of her mother’s old underwear.

The old man is named Caserta. It’s a name Delia recognises from Amalia’s past; it’s a name Uncle Filippo, the only survivor of Amalia’s generation, still curses.

The setup then is similar to that in a crime novel. We have a death; a mystery; strange characters; old secrets. If there was a crime though there’s no suggestion it was murder. The mystery here is Amalia’s life, not her death.

Troubling Love is an intensely physical novel. Delia’s period starts during the funeral. It’s heavy and unexpected. She has to buy emergency tampons and head to a filthy toilet in a local bar to put them in. As an aside, I can’t remember the last novel I’ve read where a character buys tampons. Strange that something so normal is normally so ignored.

The body, a woman’s body, is here an ambivalent space. Ferrante focuses on sweat and blood and food and sex with fascination and disgust suffusing the narrative equally. Bodies, women’s bodies, both compel and repel. She’s particularly good on how men occupy, colonize is perhaps a better word, women’s physical space. Here Delia is on a funicular:

Women suffocated between male bodies, panting because of that accidental closeness, irritating even if apparently guiltless. In the crush men used the women to play silent games with themselves. One stared ironically at a dark-haired girl to see if she would lower her gaze. One, with his eyes, caught a bit of lace between two buttons of a blouse, or harpooned a strap. Others passed the time looking out the window into cars for a glimpse of an uncovered leg, the play of muscles as a foot pushed brake or clutch, a hand absentmindedly scratching the inside of a thigh. A small thin man, crushed by those behind him, tried to make contact with my knees and nearly breathed in my hair.

One of the most uncomfortable scenes of the book is where Delia has sex. She has never got any particular pleasure from the act; she has never orgasmed. Instead she just sweats, more and more, turning the bed into a near-literal swamp.

The missing suitcase, once returned, is discovered to be filled with lingerie. It’s in Delia’s size, as was the expensive bra Amalia was wearing when she died. Underwear, the most intimate of garments, is key here. As the trade with Caserta demonstrates early on, underwear is currency. Amalia died wearing underwear bought for Delia. It’s another thread of the current of intimacy and disquieting physicality running through the novel.

Amalia was more comfortable with the male gaze. Her marriage ended in jealousy and abuse years before her death. Delia’s father couldn’t accept his wife’s independence or that other men might look at what in his view belonged to him. She was an attractive woman full of life and easy charisma and he could never forgive her for existing beyond him:

Oh yes: for that, for her charm he punished her with slaps and punches. He interpreted her gestures, her looks, as signs of dark dealings, of secret meetings, of allusive understandings meant to marginalize him.

This was Ferrante’s first novel, and perhaps that shows. There’s something quite attractive about the structure of a crime novel being used for a book which is largely about offences which never involve the police – men’s control of women and the shaming of female physicality and sexuality. There’s some great language (“Amalia had the unpredictability of a splinter, I couldn’t impose on her the prison of a single adjective.”). There’s plenty to like here.

There’s plenty too though to be less excited by. There’s repetition, particularly with that imagery of the litany or stream of obscenities which comes up several times. There’s the use of that oldest of plot conceits, the family drama buried in the secrets of the past. There’s a faint whiff at times of melodrama. There’s the fact above all that a month later I can barely remember it, and had to check my copy to remind myself what happened.

Troubling Love then for me is not a great book, nor even close to one. It’s a mostly well written book with some good and uncomfortable ideas, but built on a platform which is perhaps a little too traditional in terms of story and which at times felt like it was trying a little too hard to shock. I liked it, but I didn’t love it.

I do plan to read more Ferrante. There’s far too many great reviews of her to judge her on one book. I made a mistake though picking her first as my first, and there’s perhaps a reason this particular novel is one of her least talked about.

Other reviews

None on the blogosphere that I know of. I did however find this excellent piece from Iowa Review which is worth reading and which makes some great points about the limits of the translation. Edit: Tony, on twitter, pointed me to his (more positive) review here which is worth reading, particularly as he puts this book in the context of her other works.

Filed under: Ferrante, Elena, Italian Literature, Italy Tagged: Elena Ferrante