This book was in my cupboard for years — okay, decades. I noticed it was published during the Reagan administration when I pulled it out and decided to read it, as a counterpoint to having just finished philosopher Isaiah Berlin’s The Power of Ideas. Dave Barry would have titled that book The Power of Boogers.

This book was in my cupboard for years — okay, decades. I noticed it was published during the Reagan administration when I pulled it out and decided to read it, as a counterpoint to having just finished philosopher Isaiah Berlin’s The Power of Ideas. Dave Barry would have titled that book The Power of Boogers.

I say “cupboard” but it’s not a “board,” actually a bunch of boards assembled into what might more correctly be termed a cabinet. Nor has it any hooks to hang cups.

Anyhow, the foregoing represents my lame attempt to capture the flavor of Dave Barry’s writing. He’s no Isaiah Berlin.

My local paper used to carry Barry’s humor column. His accompanying photo, with its ridiculous smirk, looking like he’d just swallowed a mouse and was about to burst out giggling, always said to me, “Seriously?” Regretfully, googling didn’t turn up that picture to show you.

This book, Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits, begins with a chapter titled, “Why Humor is Funny.” (Berlin might have seen a tautology there.) The chapter is a probing disquisition exploring humor’s historical antecedents from Aristotle to Shakespeare to Woody Allen. I’m not making this up (as Barry himself would say). And it’s all contained within less than three pages. Of fairly large type, no less.

The best source for jokes, Barry asserts, is the Encyclopedia Britannica. No, really — its article on “Humor and Wit,” which he calls a “regular treasure trove of fun.” To substantiate this — well, actually to assure us he’s kidding — he quotes “a real corker.” Tell this joke at a dull party, Barry says, “and just watch as the other guests suddenly come to life and remember important dental appointments!” (Exclamation point in original.)

Here is the said joke:

Far be it from me to dispute Dave Barry on what’s funny or not, but I laughed out loud. In fact, the above is a conceptual mate to what is actually my own favorite joke:

Two guys in a bar start chatting. One confides, “I’m a masochist. I love pain and suffering.”

“What are we waiting for?” says the masochist.

So they go, he’s stripped to the waist, chained up to a post, and the other guy gets out this great big whip, and he’s cracking that whip, and cracking it, and cracking it.

“Well?” the masochist says impatiently. “Aren’t you going to whip me?”

And the sadist says, “No.”

We’re told that if you have to explain a joke, it’s not funny. Jokes work through ironic confounding of expectations. Here, the sadist actually does inflict pain, by denying the masochist his heart’s desire; in the shower joke, the masochist does it to himself. But both jokes have a further layer. Denial of what the masochist craves makes him suffer. Yet isn’t suffering what he really wants after all? This raises deep philosophical questions about the meaning of suffering, and of happiness, that Isaiah Berlin might address.

But it is, admittedly, a weakness in both jokes that neither involves boogers.

Here is my second most favorite joke:

A bald man [note, this is an important detail; the joke is less funny if you’re not picturing the man as bald] walks into a doctor’s office with a frog atop his head.

And the frog says, “I have this man stuck to my ass.”

Do you see what I did there? Once again, jokes are about twisting expectations. Here of course one expected the man, not the frog, to answer. My drawing particular attention to the man’s baldness served to heighten that expectation. This is the difference between mere joke telling and comic genius.

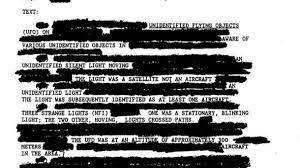

But Dave Barry really is a comic genius. One of his chapters I found especially amusing told about a 452-page document printed under the auspices of the U.S. Senate Finance Committee, with every single word crossed out. That by itself was not a laugh riot. We actually expect such absurdities in the realm of government. No, what really tickled my funny bone was that the document was on sale by the Government Printing Office, for $17 — and Barry related that 1800 copies were sold.

Being myself a person who has often written about religion, I thought I’d conclude with this trenchant observation from Dave: “The problem with writing about religion is that you run the risk of offending sincerely religious people, and then they come after you with machetes.”

I’ve indeed experienced this.