Originally published on the GE.blog.

What do you want to be when you grow up?

Unicorns, like job security, used to exist (actually, it’s an Elasmotherium)

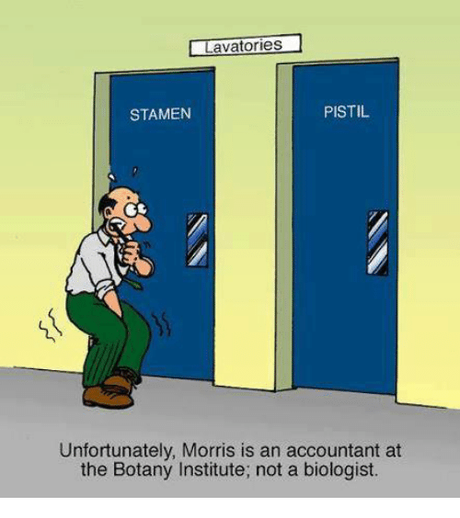

The term ‘job security’ seems a fanciful idea to budding biologists — you may as well be studying unicorns (and no, narwhal don’t count …)! Now, you’re a fully fledged adult, your thoughts are likely filled with adult questions like ‘where will I live’ and ‘how will I scrape some money together?’. Not knowing where to go next can be very stressful.

A change in profession might help with job security, but if you’ve made it this far in biology, its highly likely that you (like me) have been obsessed with biology since early childhood, and it’s not something you’re willing to give up easily. On top of that, you now have years of research experience and skill development behind you — it would be better if that experience didn’t go to waste. How, then, can we keep funding our biology addiction? I don’t want to sound like a snake-oil salesman here, so let’s be straight-up about this: there are no easy options. But, importantly, there are options — in research, the university sector, and wider afield.

So, down to the serious business. Your options (depending on your personal preferences) are:

1. Research or bust!

In-house postdoctoral fellowships

Research bodies in Australia, including many universities, the CSIRO and the Australian Museum, offer in-house postdoctoral fellowships for early-career researchers. Applying for one of these postdocs usually involves the candidate developing a research proposal and initiating collaboration with researchers in the institute offering the fellowship.

My first postdoc was one of these; it was a joint venture between James Cook University and the CSIRO, and it included a small research budget and my salary for three years full-time equivalent (although I ended up doing most of it part time over a longer period due to parenting responsibilities). I found out about this postdoc towards the end of my PhD, when I started investigating my post-PhD job options. Investigating my options early (in this case, before it was advertised) gave me the chance to be well organised — I was able to start developing my proposal and collaboration with relevant researchers before many of the other applicants. This is where your already established networks come in handy — don’t assume other researchers will tell you of opportunities coming up in the near future; make sure you seek them out, and have those conversations with everyone.

Some universities and research institutes regularly offer in-house postdocs, while others offer them intermittently. The length of these fellowships, application requirements, eligibility criteria (e.g., time since your PhD was awarded), and amount of funding varies. So, check the institute’s webpages for more information.

Here are links to some of the Australian universities that offer in-house postdocs: University of Wollongong; University of Adelaide (here and here); University of Melbourne; Macquarie University; University of Technology Sydney. You can also find lists of Australian postdoc options, including more in-house fellowships, on great webpages developed by Dr Chrissie Painting and Professor Scott Keogh.

ARC postdoctoral fellowships

Depending on your career stage, you could apply for an Australian Research Council fellowship such as a Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DECRA) or a Future Fellowship. This is perhaps the most obvious option for early-career researchers in Australia. It’s also sometimes viewed — correctly or incorrectly — as the gold standard in academic progression. Securing one of these fellowships is highly competitive and the application preparation is time-consuming (people say it takes a month or two to write a good DECRA application).

But on the upside, these fellowships can be tailored to follow your particular interests because the application involves developing a research proposal. So, if you have a great idea for a research project, a strong track record, the right research environment/team to make it happen, and the time to prepare a competitive application, applying for an ARC fellowship could be a good idea for you. To find out what’s involved in terms of preparing your application, eligibility criteria, and important dates, information and support are provided by most Australian universities online (e.g., at Flinders University) and through workshops they offer. If you decide to apply for one of these fellowships, be well-organised so that you’re competitive and the timing works out for you, because there is a big lag between applying for one of these fellowships and when the money starts to ‘flow’.

Similar fellowships are available overseas, for which you could also consider applying depending on your eligibility and flexibility to relocate, e.g., Royal Society of New Zealand (Marsden Fund); Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC Banting postdocs) in Canada; National Science Foundation (NSF) or Smithsonian Institution Fellowships in the USA; and the European Research Council (Marie Curie Fellowships).

Advertised postdoctoral fellowships for predefined projects

Researchers and research centres often advertise postdoctoral fellowships tied to projects for which they have already secured funding. These postdocs are not as flexible in terms of research direction as in-house or ARC postdocs, because they are associated with predefined projects, i.e., your research output must align with the pre-defined project (whereas you design the research project yourself in the case of ARC and in-house postdocs).

My second (current) postdoc is one of these ones. I found out about it through an email sent from a friend. The project, which is on Late Pleistocene megafauna extinction in Sahul, sounded really interesting to me, and so being ‘restricted’ by the project wasn’t an issue. I contacted the professor advertising the position to ask him about the project; it was a little outside my area of expertise, and so I wanted to check whether I would be competitive if I applied. He advised me that I would be competitive, and so I applied and was lucky enough to get the job. I’m now more than a year into this postdoc, and I’ve found the research intriguing (steep learning curve and all!) and feel there has been plenty of freedom/flexibility within the limits set by the project.

If you’re interested in applying for postdocs that are linked to already funded projects, these opportunities are often posted on the web/Facebook pages of research societies such as the Australasian Evolution Society, Ecological Society of Australia, and the Australian Society of Herpetologists. Labs advertise positions on their own webpages and twitter feeds, and these positions are also sometimes advertised on webpages specifically dedicated to research positions (e.g., EvolDir, and Nature Careers) and more general vacancy advertisers (e.g., THEunijobs and SEEK) — and you can set up job alerts on some of these websites.

Researchers often advertise postdoc positions associated with predetermined projects through research societies.

2. I want to stay in the university sector no matter what (even if I can’t do my own research)

Non-postdoc university options in research and teaching

If you’re keen to stay in biology in the university sector, there are alternatives to doing a postdoc. These include working as a research assistant, laboratory demonstrator, or lecturer. Tenured lecturer positions in Australia are highly sought-after, and in most cases you’ll need to have both postdoctoral research and teaching experience under your belt to be competitive. However, there is movement towards teaching-specialist positions (i.e., teaching-only), and so prerequisites relating to experience in research may become more relaxed.

Short contract and casual work as a research assistant or lecturing/tutoring is commonplace among PhD students and recent graduates. After my PhD, and between postdocs, I did this kind of work. In most instances, I got the work through people I had worked or studied with previously — testament to the fact that developing your network comes in handy when you’re looking for a job. Short-term positions are sometimes only advertised internally on a university’s current vacancies webpages (e.g., Flinders University and James Cook University), and not through external employment advertisers such as SEEK, so you need to check individual university websites for these.

Some vacancies at universities are only advertised on the university’s employment webpages.

University jobs using generic skills

In addition to jobs in your research area, there are other university employment opportunities for which you may be well-suited. These are jobs that take advantage of the generic skills you’ve developed while doing your research, like data management, statistics, writing, communication, and project management. Your experience working in a university and dealing with the associated bureaucracy will be an advantage when applying for one of these positions.

Jobs in this category are diverse, ranging from research support officers helping with grant applications, data scientists/analysts, ethics and permits officers, remedial skills and bridging course teachers/lecturers, and positions associated with other student and staff support services. I’ve done one of these jobs, too. I saw a vacancy for a predictive analytics and teaching quality data specialist advertised internally by a university. It was a 10-month position, and the work involved crunching undergraduate student enrollment and attrition data to assess which intervention strategies were helping retain students and getting them through their degrees. Although it wasn’t biology, it was still really interesting because I got to play with data and see how the university worked from a different perspective (and the pay was pretty good too!). As with university research jobs, these employment opportunities are often only advertised internally, so check the university’s vacancies webpage.

You may be interested in non-biology jobs at uni.

3. There is a big wide world out there

Jobs outside university using the skills you have developed

As a PhD student or postdoc, we’re stuck in a bit of a university bubble; our work interactions and collaborations are mostly with other people at university. This bubble can act as a barrier to getting jobs outside the univesity sector for two reasons:

- our professional networks are biased towards including other people from the university sector, and

- the re-employment focus while doing research at university is usually on getting more research work at university.

However, many people end up leaving the sector. In a quick scan of my facebook friends that have a PhD or Masters, I found that nearly half had already left the university sector. This isn’t that surprising, when you consider the broad range of jobs and employers outside university that are suitable for trained biologists. These jobs include positions that require your knowledge in biology, as well as positions that take advantage of the generic skills you have developed.

There are, for example, biology jobs in government organisations such as CSIRO, NSW National Parks and Wildlife Services, state environment and primary industries departments, state museums, local councils, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, and the Australian Institute of Marine Science. There are also biology jobs in environmental NGOs including environmental consultancies and conservation groups (e.g., Australian Wildlife Conservancy, Bush Heritage Australia, World Wildife Fund, etc.).

To find non-university jobs in biology in Australia, you can search and set up alerts for vacancies on NRMjobs. Also, state governments often only advertise jobs in their agencies on their own websites (check these links and/or set up alerts for State and Territory Government jobs: SA, QLD, NSW , VIC, TAS, WA, NT, ACT).

If you’d like to make the move out of the university sector into a different organisation, it’s good to talk to people that already work in that organisation to get tips on how to make the switch. It also can’t hurt to start collaborating with people in that organisation, and incorporating the development of skills required by the organisation into the research you’re doing (if possible). In applying for jobs outside academia, employers will likely place a much higher weight on the skills you offer than on your publication record — an important point to keep in mind when preparing your CV and responses to selection criteria.

NRMjobs advertises environmental jobs across Australia.

Self-funded research

Some researchers apply their scientific skills to business, and then use the profits to support their research. This is not a common pathway (I don’t personally know anyone who has done this over the long term), but there are examples of scientists from a range of disciplines who have done this successfully. For example, Stephen Wolfram, a physicist and mathematician by training, is the CEO of the software company Wolfram Research.

Among other programs, Wolfram Research developed the answering engine WolframAlpha, which is what Siri uses when you ask it questions. Wolfram himself has been able to step back from the business side of his company, hiring other people to handle that, and instead focus on his research interests such as searching for a theory to explain all of physics and other small questions like that … So, self-funding your research over the long run might sound like pie in the sky, but it is possible.

Start your own business

Have you ever considered starting your own business as a goat, oyster, or mushroom farmer? These are all examples of businesses friends have gone into after doing PhDs in biology. In the oyster farmer’s case, the PhD research provided experience directly relevant to the new business. In contrast, the goat and mushroom farmers’ backgrounds were in herpetology — their research was less-relevant to the businesses they developed, but they still made it happen. So, whether or not your research experience aligns closely with the business you’d like to start doesn’t matter that much — either way you can make it work, and many of the skills you’ve developed as a biologist will come in handy. For me, someone who hasn’t tried his hand at this, the idea of starting a business is pretty intimidating — my respect to anyone who has a crack at this!

4. I’m still not qualified enough

Retrain or gain supplementary qualifications

Have you not studied enough yet? Many biologists (and other scientists) go back to uni to get professional degrees to qualify for specific jobs. For example, some of my friends have added a teaching qualification so they can teach in primary or secondary schools, while others have gone back and studied medicine or other health sciences. Indeed, one friend with a PhD in physics is now completing her midwifery training — that’s a bit of a switch!

I personally completed my teaching qualifications while I was working as a TAFE teacher, between my Honours and PhD, as a safety net so I could go back to teaching if required/desired. Of course, teaching and health sciences aren’t your only options — with a BSc degree, an Honours/MSc, and a PhD under your belt, the world of university courses is your oyster (you just need to stay motivated).

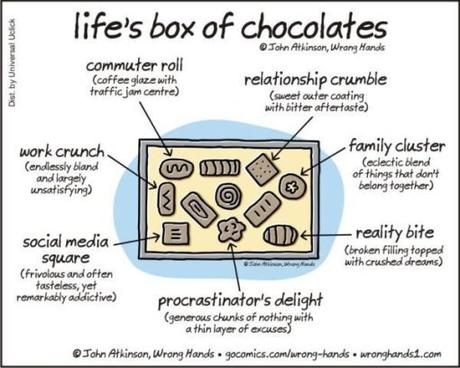

Life is like a box of chocolates …

Our career options as trained biologists are pretty broad. This might not help when we’re trying to figure out what exactly we’re going to be when we ‘grow up’, but it means we’ve got lots of options — decisiveness is a virtue. Above, I’ve gone through the options I can think of, but I would’ve missed some options. If you’ve got any ideas you’d like to add, including other career paths or tips for getting jobs, please post them in the comments below.

Finally, I wish you good luck with whichever path you choose. It can be a rocky road, but let’s enjoy the journey!