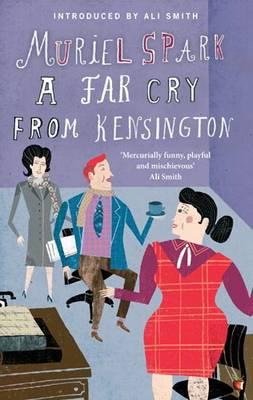

A Far Cry From Kensington, by Muriel Spark

Many (many) years ago I read The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. I’d guess that it’s the only Muriel Spark most people have heard of (because of the film). It was excellent, but somehow I wasn’t prompted to read more. It felt like I’d read the essential work. I hadn’t of course. I’d just read the famous one.

Recently I decided to give Spark another try and I chose A Far Cry from Kensington for the simple reason that I grew up in Kensington and it seemed that might lend it some personal interest. It’s a pretty random reason to read a book, but it worked out because Far Cry is quite simply superb.

Superb incidentally is very much a post-reading judgment. Early on in Far Cry I thought it rambling and baggy. It isn’t and by the time I’d finished I realised it was one of the more tautly constructed novels I’ve read this year. Stick with it.

The book opens with the narrator, Mrs Hawkins, lying awake with her mind turning back to her time living in Kensington in 1954. Years have passed. She no longer lives in London and it wouldn’t matter if she did because the Kensington of her today is a far cry from the Kensington of back then. This is a reverie of a lost world.

In 1954 Mrs Hawkins is young and enormously fat (it’s relevant). She works in an upmarket publishing house in the West End, mostly fobbing off authors and print companies who’re all chasing payment. The business is going bust and she soon reveals that her boss Martin York eventually went to jail for fraud.

Martin York isn’t a bad man. He overextended and overjuggled and ultimately comes unstuck committing a stupid forgery in the hope of buying a little more time. At his trial the judge reproves him with the words “Commercial life cannot be carried on unless people are honest” before sentencing him to seven years. A harsh penalty for a foolish misjudgment, but the penalty for honesty is one of the themes of this book.

In the evenings Mrs Hawkins goes home to a rooming house in downmarket South Kensington. Her landlady, Milly, is a charming but still respectable Irishwoman who runs a reputable house. The other tenants include a quietly middle-aged married couple, a medical student, a district nurse, a young woman with family income, and a polish dressmaker named Wanda Podolak. Like the publishing house few of them have much money. The difference between the people at work and at home is one of attitude, or perhaps of honesty:

At Milly’s in South Kensington, everybody paid their weekly rent, however much they had to scrape and budget, balancing the shillings and pence of those days against small fractions saved on groceries and electric light; at Milly’s, people added and subtracted, they did division and multiplication sums incessantly; and there was Kate with her good little boxes marked ‘bus-fares’, ‘gas’, ‘sundries’. Here, in the West End, the basic idea was upper class, scornful of the bothersome creditors as if they were impeding a more expansive view.

Both at Milly’s and at work Mrs Hawkins is much relied upon:

There was something about me, Mrs Hawkins, that invited confidences. I was abundantly aware of it, and indeed abundance was the impression I gave. I was massive in size, strong-muscled, huge-bosomed, with wide hips, hefty long legs, a bulging belly and fat backside; I carried an ample weight with my five-foot-six of height, and was healthy with it. It was, of course, partly this physical factor that disposed people to confide in me. I looked comfortable.

There are two more key elements to throw into the mix. The first is at work:

At this point the man whom I came to call the pisseur de copie enters my story. I forget which of the French symbolist writers of the late nineteenth century denounced a hack writer as a urinator of journalistic copy in the phrase ‘pisseur de copie’, but the description remained in my mind, and I attached it to a great many of the writers who hung around or wanted to meet Martin York; and finally I attached it for life to one man alone, Hector Bartlett.

Hector Bartlett: he’s hanger-on to the famous and highly regarded author Emma Loy; a writer of terrible prose who uses his connections to get published; a man so petty that when in one scene a dog in a pub snaffles part of his sausage roll he dunks the remaining bit in mustard before feeding it to the unsuspecting animal.

Bartlett is entirely without merit, but nobody in the publishing world dares say so because Emma Loy is too important to upset. Nobody that is save Mrs Hawkins who calls him a “pisseur de copie” to his face and then repeats the phrase to anyone who asks what she did to offend him. If challenged why she said such a thing she merely replies that it’s true and says it again.

The second key element is at home. Wanda Podolak receives a poison pen letter:

Mrs Podolak, We, the Organisers, have our eyes on you. You are conducting a dressmaking business but you are not declaring your income to the Authorities. Take care. An Organiser.

The only people who know about Wanda’s business are her friends, housemates and clients. The letter must come from someone she knows and trusts and that fact poisons her life. Someone is smiling to her face but intent on harming her.

Emma Loy has Mrs Hawkins fired for the pisseur de copie remark and over the course of the novel continues to make Mrs Hawkins’ life difficult. Loy has power in Hawkins’ world but Hawkins isn’t willing to cover her truth with a convenient lie. Mrs Hawkins suffers for her honesty, but at least knows where she stands and who stands against her. Wanda by contrast is completely lost.

Perhaps at this point you can see why I initially found the book a bit baggy. There was so much going on: the collapsing publishing house; the feud with Hector Bartlett and Emma Loy; Mrs Hawkins’ subsequent publishing jobs; the poison pen problem. Amidst all this Mrs Hawkins constantly makes retrospective asides to the reader commenting on the situations she encountered or the people she met while all this was going on. All I can say that Muriel Spark knows what she’s doing and is in complete control of her material. You can trust her.

What particularly stands out for me in Far Cry is the lightness of Spark’s touch. This is a very funny book. Mrs Hawkins is constantly offering advice, both to those around her and to the reader. She loses weight by just eating half of whatever’s put in front of her and offers this as a tip to the overweight reader “without fee, included in the price of the book”. Every few pages she passes someone “some very good advice”, and much of it is pretty good but there’s certainly a lot of it. My favourite, easily, was this:

It is a good thing to go to Paris for a few days if you have had a lot of trouble, and that is my advice to everyone except Parisians.

Quite. What could one add?

The comedy leavens the tragedy. There’s a lot of serious stuff here: embittered hack writers; an imprisonment for fraud; the poison pen letters; and later some of the characters attach far too much credence to the quack-claims for an obviously fake box-apparatus that supposedly can be used to heal the sick (to me fairly obviously based on Orgone boxes save that here you don’t climb inside).The material could choke, but as with Bainbridge the treatment is so light that even at its darkest the book is a delight to read.

I’ll end with one final quote, taken from one of Mrs Hawkins later jobs where she becomes a literary editor. Her approach is one I would recommend to anyone else considering that profession:

‘When you are editing copy, Mrs Hawkins, what sort of things do you look for?’ said Howard Send. ‘Exclamation marks and italics used for emphasis,’ I said. ‘And I take them out.’

My advice to any aspiring writer who may happen to read this is to do as Mrs Hawkins does. She is, in this and many other things, quite right.

Other reviews

I actually don’t have any noted, but I suspect I may have missed some. If I have please let me know in the comments.

Filed under: Spark, Muriel Tagged: Muriel Spark