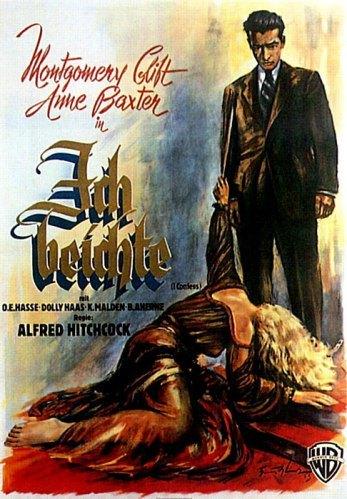

Hitchcock films get mentioned and written about all the time, but it’s almost always the same dozen or so that receive all the attention and plaudits. A good many of his movies are really only spoken of in passing, often referred to as bridges between his major works and, while it’s rare to see them dismissed outright, it sometimes seems that the perceived flaws and (relative) lack of success is what draws most comment. I Confess (1953) probably belongs in this category, being regarded as a little too personal and flirting with inaccessibility as far as non-Catholics are concerned. Whatever the popular view might be, it’s a film I’m very fond of, and one which of course contains the now familiar wrong man theme.

The movie opens in a typically quirky and macabre fashion, a succession of street signs flashing before our eyes and leading inexorably to the scene of a murder. As the camera peers through the open window the corpse is laid out on the floor and the door is just closing on the exiting killer. We follow the murderer through the shadowy, cobbled streets, his silhouetted figure suggesting a clergyman. Then, as he casts off the soutane, it becomes apparent that the priestly garb was no more than a convenient disguise, no doubt inspired by the fact that this man earns his keep working for the church. When a man has committed the ultimate sin, has compromised his soul and is wracked with guilt and fear, then it’s not unnatural that he should seek solace and sanctuary in a holy place. The man in question is Otto Keller (O E Hasse) and his entering the church is witnessed by chance by one of the priests, Father Michael Logan (Montgomery Clift). Keller insists that Fr Logan hear his confession and the latter duly obliges. Much has been made of the fact that non-Catholics may have difficulty appreciating the seal of the confessional, the inability of a priest to ever reveal what he hears under such circumstances. I understand how there are those who might be unaware of this but the absolute confidentiality is made clear in the script so I think it’s not really reasonable to criticize the film on this score. Anyway, both the viewers and Fr Logan are aware of the identity of the murderer almost from the beginning, but further complications are to arise and cast official suspicion in a different direction. If all those signs in the opening sequence led us to a dead man, another set of pointers lead the police, headed up by the dogged and practical Inspector Larrue (Karl Malden), towards Fr Logan. The murderer’s literal cloak of convenience helps of course, but the priest’s connections with the victim, a blackmailing, shyster lawyer, fan the flames of suspicion. As the reasons for Logan’s seemingly odd behavior are laid bare and the object of the blackmail becomes known, the priest’s refusal or inability to speak up damns him in the eyes of the law. With the wheels of blind justice now in motion, Logan finds himself morally trapped and apparently powerless to protect either himself or those he cares about.

Anyone who has ever read anything about Hitchcock will be aware of two facts: his Catholic upbringing, and the distrust he felt for the law and the institutions of justice. Both of these influences on the director’s life are very much to the fore in I Confess. Church dogma colors every aspect of Logan’s behavior throughout, cutting down his options and, again through no fault of his own, leaving both him and those around him exposed to misguided moral outrage. And of course all this leaves him at the mercy of a justice system which is unsympathetic to what it’s unaware of. Essentially, Hitchcock is presenting us with an ethical conundrum, a true dilemma where betrayal (be it spiritual or emotional) lies in wait whichever path is chosen. Really, it’s a classic noir scenario, with fate seemingly laying a complex and delicate trap for the unsuspecting protagonist – every act, the noble and the innocent most of all, being misconstrued and misinterpreted. Robert Burks lighting and photography, particularly the night scenes, is bathed in expressionistic shadow and Hitchcock blends the tilted angles, telling close-ups, tracking shots and deep focus beautifully. You could say the symbolism is laid on a touch heavily at times – the allusion to the trek to Calvary springs to mind immediately – but it’s all so wonderfully composed that it sounds a little churlish to harp on it too much.

I’ve mentioned before that I’m not a fan of the Method approach to acting, finding it phony and distracting for the most part. However, there are always exceptions, and it’s nice to be able to highlight a positive example. Montgomery Clift was one of the first (perhaps the first?) practitioners of the Method on the big screen, and I feel he was generally very successful. I like internalized performances and I like subtlety, and Clift was a first-rate exponent of this. Great screen acting comes from the little things, the barely perceptible changes of mood and the altered thought processes which we sense as much as see. Clift had many blessings but among the most significant were his composure and his eyes. The early scene in the confession box is a marvelous bit of work with those eyes revealing so much. And the same can be said for every important plot development – the increasing desperation and hopelessness of the situation is perfectly conveyed but never exaggerated. At one time I felt that Anne Baxter was less than satisfactory as Clift’s former love, but I now feel she judged it well enough. Again, it’s a role that calls for as much to be held inside as freely expressed. The longish flashback which clarifies the nature of her relationship with Logan is told from her point of view and it’s probably here that she comes across best. Frankly, there are good performances all round: Malden’s probing and restless detective, Brian Aherne’s rakish prosecutor, O E Hasse as the craven yet pitiful killer, and of course Dolly Haas as his conscience-stricken wife.

A film like I Confess, one which is so heavily dependent on its visuals, needs to be seen in good quality. Fortunately, the Warner Brothers DVD offers a strong transfer that shows off the contrast between light and dark to good effect. It’s clean and acceptably sharp, a solid-looking presentation. The disc also has a “Making of” documentary included, which provides some analysis along with production and background information – a worthwhile extra in my opinion. The film continues to be underrated as far as I can tell, and that probably says more about the strength of Hitchcock’s body of work than it does about the movie itself. I reckon it accomplishes about all it sets out to do but others may disagree with that assertion. Either way, I’d urge people to give it a chance, or perhaps watch it again if they’re already acquainted with it – I believe there are plenty of positive aspects to focus on.