Here at ConservationBytes.com, I write about pretty much anything that has anything remotely to do with biodiversity’s prospects. Whether it is something to do with ancient processes, community dynamics or the wider effects of human endeavour, anything is fair game. It’s a little strange then that despite cutting my teeth in population biology, I have never before tackled human demography. Well as of today, I have.

Here at ConservationBytes.com, I write about pretty much anything that has anything remotely to do with biodiversity’s prospects. Whether it is something to do with ancient processes, community dynamics or the wider effects of human endeavour, anything is fair game. It’s a little strange then that despite cutting my teeth in population biology, I have never before tackled human demography. Well as of today, I have.

The press embargo has just lifted on our (Barry Brook and my) new paper in PNAS where we examine various future scenarios of the human population trajectory over the coming century. Why is this important? Simple – I’ve argued before that we could essentially stop all conservation research tomorrow and still know enough to deal with most biodiversity problems. If we could only get a handle on the socio-economic components of the threats, then we might be able to make some real progress. In other words, we need to find out how to manage humans much more than we need to know about the particulars of subtle and complex ecological processes to do the most benefit for biodiversity. Ecologists tend to navel-gaze in this arena far too much.

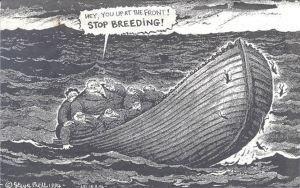

So I called my own bluff and turned my attention to humans. Our question was simple – how quickly could the human population be reduced to a more ‘sustainable’ size (i.e., something substantially smaller than now)? The main reason we posed that simple, yet deceptively loaded question was that both of us have at various times been faced with the question by someone in the audience that we were “ignoring the elephant in the room” of human over-population.

Human population size has always been a sticky issue, for it evokes all sorts of emotions and sentiments that have nothing to do with science. Everything from religious freedoms to human rights are brought to the fore, with horrible examples of where some societies have pulled demographic levers to and beyond their ethical limits (think eugenics, enforced one-child policies and genocide). I want to make it clear that it was not our intention to advocate any of these extremes – we merely wanted to know what even the unfathomable could do to the human population trajectory over the coming century.

As any conservation biologist will attest, if we can’t get the human population to more sustainable size, most of our efforts to conserve biodiversity will be futile. But population size is only one part of the famous ‘I=PAT‘ equation of Holdren & Ehrlich (1974): Impact = Population size × Affluence (per capita consumption) × Technological and sociological choices. Arguing whether P or A is more important is like arguing that length is more important than width for determining the area of a rectangle – the two are inseparable.

So back to that central question – how fast can we get the P side of the equation down? As it turns out, not very fast at all. We investigated 10 different scenarios where the fertility and/or survival probabilities changed gradually or in a stepped function, mimicking everything from gradual fertility reductions to all-out catastrophic mortality scenarios (emulating world wars or global pandemics). The take-home message is that even extreme scenarios will not deliver a major reduction in human population size this century. It is a process that will take centuries to occur, rather than decades. Unfortunately, we only have decades to act.

We also examined where in the world biodiversity will most likely be affected by human population increase. We did this very simply be examining regional population trajectories within the existing 35 Biodiversity Hotspots. Few prizes for guessing where the most damage to endemic species will likely occur – most of Africa and the subcontinent. Will my daughter ever get to see rhinos and African elephants in the wild? Unless I take her there soon, it’s increasingly unlikely.

As such, our immediate sustainability gains will be better served by tackling the A & T parts of the equation, but this does not mean we should ignore the P. On the contrary, we should implement global-scale family planning to reduce P as much as possible. Hundreds of millions fewer people stressing our planet’s resources and biodiversity could result if we do, and if we don’t start somewhere, slowing the speeding car in the future will be even more difficult than it already is. Had we seriously addressed the issue before it became so intractable (say, 50 years ago), we might not now find ourselves in such a mess. What can I say? Humanity isn’t notorious for forward thinking.

CJA Bradshaw