Martin Ritt's greatest work is Hud (1963), less modern Western than Texas chamber drama. Certainly it's one of Paul Newman's best roles, warping his charming persona into something hateful. But Newman's buoyed by a flawless script and brilliant supporting cast, resulting in one of the '60s great dramas.

Martin Ritt's greatest work is Hud (1963), less modern Western than Texas chamber drama. Certainly it's one of Paul Newman's best roles, warping his charming persona into something hateful. But Newman's buoyed by a flawless script and brilliant supporting cast, resulting in one of the '60s great dramas.Based on a Larry McMurtry novel, Hud focuses on the Bannons, a Texas ranching clan. Homer (Melvyn Douglas) is the proud patriarch who's outlived his time; Hud (Paul Newman), Homer's wayward son obsessed with booze, broads and brawling. Their testy relationship comes to a head when their cattle catch foot-and-mouth disease, threatening the Bannons' livelihood. Teenaged Lonnie (Brandon De Wilde), Hud's nephew, grows torn between the two father-figures. And Alma (Patrica Neal), Homer's feisty housemaid, becomes the subject of Hud's unwanted attentions.

Hud turns the cowboy hero into a modern-day monster. Cast adrift in the 20th Century, his admirable traits prove decidedly unappealing. He expends his toughness not on useful work but fights and boozing. He parades married women on his arms and thinks it okay to assault one who dares resist him. Hud's rants against government interference are self-serving hooey: he wants to loose the infected cattle, knowing full well they'd infect other herds. His machismo is aimless destruction, his self-reliance narcissism.

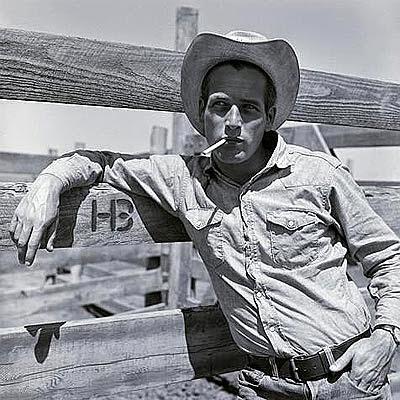

Paul Newman's natural charisma makes Hud compelling, which only highlights his nastier side. Newman specialized in charming antiheroes but his appeal's skin-deep. Whatever personal baggage he carries (his guilt about his brother) Hud has no principles, happy to drag others into the abyss. Newman bores down on the character's unpleasant, using his flashing eyes and roguish smile to mask a soulless brute.

Yet Hud's far from a one-man show: Ritt and writers Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank, Jr. give the supporting cast room to shine. Homer's code sounds honorable, yet his age and poor decision making can't make it stick. It's not Hud's irresponsibility but Homer's own errors (buying cheap Mexican cattle) which doom his ranch. Lonnie's more reactive, emulating Hud's reckless actions and Homer's moral posturing. Alma's the most sympathetic: damaged from a bad marriage, she hides mistrust behind a flinty exterior.

Yet Hud's far from a one-man show: Ritt and writers Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank, Jr. give the supporting cast room to shine. Homer's code sounds honorable, yet his age and poor decision making can't make it stick. It's not Hud's irresponsibility but Homer's own errors (buying cheap Mexican cattle) which doom his ranch. Lonnie's more reactive, emulating Hud's reckless actions and Homer's moral posturing. Alma's the most sympathetic: damaged from a bad marriage, she hides mistrust behind a flinty exterior.Melvyn Douglas gives a stellar turn, rough, weathered and weary - far removed from his matinee idol days. Douglas provides subdued anger and melancholy, whether chewing out Hud or watching his herd destroyed. Patricia Neal matches him with earthy humor, brittle strength and cracked vulnerability. Even Brandon De Wilde (Shane) fares well, making Lonnie callow yet redeemable.

Rittthrows these outcasts into a harrowing depiction of decaying Americana. James Wong Howe's black-and-white photography makes the Texas range beautiful but foreboding, its town a sweaty collection of seedy dives. Ritt truly captures desperate small-town boredom, alleviated by folksy frivolity like a Kiwanis meeting or Saturday night dust-ups. Or by destruction: the movie's key set piece comes when Homer's ranchers execute dozens of infected cattle. No starker metaphor for the American Dream's destruction can be found.

For all its cynicism, Hud offers some hope. Lonnie ultimately rejects his uncle's wild ways, leaving Hud wandering the winds like a modern Ethan Edwards. For all Ritt's pessimism, tragedy isn't a foregone conclusion. Society's only doomed if it accepts Hud as a role model.