The first principle is that you must not fool yourself – and you are the easiest person to fool. – Richard Feynman 1974

> How To Think Like a Product Manager: Overcoming Cognitive Bias" />> How To Think Like a Product Manager: Overcoming Cognitive Bias" data-rjs="https://www.nodesagency.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Blog-post-illustrations.png" height="540" width="960" alt="Blog post illustrations - How To Think Like a Product Manager: Overcoming Cognitive Bias" srcset="https://qu6oa42ax6a2pyq2c11ozwvm-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Blog-post-illustrations.png 960w, https://qu6oa42ax6a2pyq2c11ozwvm-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Blog-post-illustrations-300x169.png 300w, https://qu6oa42ax6a2pyq2c11ozwvm-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Blog-post-illustrations-768x432.png 768w" class="vc_single_image-img attachment-full" />

> How To Think Like a Product Manager: Overcoming Cognitive Bias" />> How To Think Like a Product Manager: Overcoming Cognitive Bias" data-rjs="https://www.nodesagency.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Blog-post-illustrations.png" height="540" width="960" alt="Blog post illustrations - How To Think Like a Product Manager: Overcoming Cognitive Bias" srcset="https://qu6oa42ax6a2pyq2c11ozwvm-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Blog-post-illustrations.png 960w, https://qu6oa42ax6a2pyq2c11ozwvm-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Blog-post-illustrations-300x169.png 300w, https://qu6oa42ax6a2pyq2c11ozwvm-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Blog-post-illustrations-768x432.png 768w" class="vc_single_image-img attachment-full" />

What are cognitive biases?

A cognitive bias is a systematic error in the way that you understand and use information. To be clear, I’m not talking about mistakes or slips that happen when you’re having an off day. It’s about getting stuff wrong, consistently, without really realising you’re doing it. They are mental traps that we fall into all the time. These traps reduce our ability to think critically and make reasoned decisions. They’re not all bad, of course.

Cognitive biases are the result of us developing ‘mental shortcuts’. On the whole, this sounds very useful as it saves us time, energy and risk in lots of common situations. Here’s an example:

I just saw a chicken get struck by lightning. Given this unfortunate event, it’s a useful mental shortcut for me to err on the side of caution and assume that it’s likely I might get hit by lightning too. Therefore I don’t take the risk of hanging around to find out. In reality, it’s highly unlikely that I get injured by a lightning strike because I’m in a car, which would dissipate any strike. But this useful information is way back in the distant memory of GCSE physics.

This example illustrates the availability bias. Given something happened recently (especially when it’s emotional), it is more available in my memory. It’s at the ’top of the pile’, so to speak. Therefore it has greater prominence in the information used to assess a new situation. Here, having cognitive bias seems pretty handy.

However, it’s not all near escapes and fried chicken. The M.O. of most cognitive biases’ is to generalise or group information. This can lead to cognitive biases being inaccurate, disruptive and dangerous. Being able to think clearly and in an unbiased way is an incredibly important skill for a Product Manager. We must be able to assimilate complex information and dispassionately use evidence and principles to direct difficult decisions which have impacts across multiple disciplines. That’s going to be tricky when your brain is secretly cutting corners.

Cognitive biases have the potential to derail a product strategy, misinform a roadmap or to steer a key stakeholder the wrong way. In other words, they can potentially make you a less effective Product Manager. There are some common types of biases which Product Managers need to be particularly wary of. What are they and how can we ensure we maintain effectiveness by reducing systematic errors in our thinking?

Bias 1: Rose-tinted spectacles

Confirmation bias describes the weakness to search for, interpret, focus on and remember information in a way that confirms your existing preconceptions. If you believe that all dogs are friendly, every time you meet a friendly dog you will assign a disproportionately large weighting to this experience, thereby reinforcing your preconception that they truly are a human’s best friend. Simultaneously, you would give a disproportionately small weighting to that dog who barked at you. It was a one off, forget it. Related to this is the observer-expectancy effect. This is when someone investigating a problem expects a given result and therefore unconsciously manipulates the investigation, or misinterprets the results in order to find the result they were looking for. These biases show that unconsciously, we are trying to construct a narrative which how we’d like the world to be.

Let’s say that you think your users want more gamification. Confirmation bias will lead you to seek out evidence in support of that, rather than looking at the evidence as a whole and weighing opposing views and positions equally. If you plow on with the assumption that you already know what needs to be done, then you will almost certainly never prove yourself wrong. Observer-expectancy effect is particularly dangerous in user interviews and testing, because the bias can subconsciously change the way you ask questions, and reinforce responses.

What can you do about it?

Having rose-tinted spectacles feeds on your individual point of view and perspective. So when it comes to decision making and reviewing data, results and insight, you need to take yourself out of the equation; remove your biased filter. You need to actively hold a devil’s advocate position to adjust your frame of reference. Step out of your shoes and into those of someone else. This could be the user, a colleague or a stakeholder. Occam’s razor is another handy (and sadly metaphorical) tool, which states that the explanation that requires the fewest assumptions is usually the right one. Using this, you’ll be able to cut out the unnecessary assumptions which your preconceptions may have fed.

Bias 2: Mob mentality

Have you ever noticed that when someone really wants their idea to gain traction, they just keep repeating it? Toddlers and politicians are masters of this. Both groups are exploiting the availability cascade. Similarly to how my recent knowledge the electrically charged chicken was more available to me, therefore colouring my future judgement, the availability cascade is a self-reinforcing process in which an idea becomes more plausible through its increasing repetition in public debate and conversation. In other words, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Even with zero evidence!

As if this fire wasn’t potentially dangerous enough, lying just within arm’s reach is the lighter fuel and kindling of the bandwagon effect and groupthink. As the name suggests, the bandwagon effect is when someone tends to do (or believe) things because many other people do (or believe) the same. Groupthink occurs within a group of people who all want to keep each other happy, so they avoid conflict and just try and maintain peace. These three biases all inhibit the critical thinking on alternative viewpoints.

This type of bias is all about stakeholders, communication and controlling team working sessions and discussions. If you are debating a product decision in a group, especially with stakeholders who are not as close to the product process, it’s very easy for ideas which may not necessarily be the best options to rise to the top. This is especially dangerous if senior authority is a factor. If a bad product idea is taken and communicated to users or stakeholders before the idea has actually been validated in the roadmap (this is obviously a pretty terrible idea), then every time it is repeated in updates, comms and meetings, another nail is hammered into the product’s coffin.

What can you do about it?

When protecting against the mob mentality biases, you have to leave emotion at the door and have an objective point of reference for decision making. Ideally, this takes the form of the rules and principles for UX, tech and business in a product strategy. These help you navigate debate productively. It’s really important that you do not try and deal with this bias by inhibiting or avoiding debate. As the product manager, you must encourage but police constructive debating; arguing doesn’t have to be argumentative. If you believe a bad (or at least unproven) idea is snowballing with the availability-cascade then you need to cast a critical interrogation lamp in its over-excited face. The Socratic method of arguing has had a rebrand and is now called ‘the five whys’. Whatever you call it, this technique is as simple as it is effective. You just keep debating and asking ‘why’ until you can agree that either the idea is worth pursuing, or needs to be dropped.

Bias 3: Skewed by context

How we consider and assess a new idea is heavily influenced by where it came from and how it was presented. This is used all the time by salespeople. If they want to sell you something they will often show you something first which they know is too expensive. Only then, will they present you with the option you want. By showing you something expensive at first, they are leveraging the contrast effect. In contrast to the first option, the second one looks like great value. A related bias is the framing effect. This describes how someone can come to completely different conclusions about something, based on how that information was presented. For example if a new venture for a business is presented as ‘an exciting opportunity to gain a competitive advantage’, this is likely to garner a very different response from the shareholders to ‘a very expensive and risky change to operations’.

This bias is all about relativity. Information does not exist in a vacuum and is always influenced by what is presented before, after and around it. For example, when you’re assessing product performance, data points will seem better is they are contrasted with unrealistic or irrelevant reference points.

Given that this article is about how the broad, generalist role of a product manager leads to challenges through processing varied information from different sources, you can see how this bias is a particularly potent one. The circumstances under which this can arise are as broad as the role itself. Therefore, the product manager needs to calibrate constantly and try to start from a blank slate when processing information. However, you can’t just forget everything else, that would be crazy. You have to only use what you know is correct. The technique for doing this is to argue from first principles.

What can you do about it?

The ability to argue from first principles is the foundation of critical thinking and roots decisions in facts. This involves taking only what you know to be correct and constructing a logically sound argument in favour of a position from that starting point. This really is the golden rule for preventing cognitive biases, it forces a very deliberate, reasoned approach to decision making which bypasses the mental shortcuts which we have developed. It’s difficult, time consuming and often inflammatory to do this. But if you care about building the right thing for your users and business, it is essential that you practice and master this skill.

If you only take one thing from this article…

The most important tool for a product manager to have for preventing against all of the cognitive biases outlined in this article is a sound product strategy. By its nature, a product strategy is a long-term view which helps you remember why you and the product are here in the first place. By their nature, most cognitive biases operate in the short-term. They build over time to exponentially increase their impact. Therefore, keeping your product strategy alive, relevant and very close to all decisions will help you argue from first principles, adopt a devil’s advocate position and continue asking “why?”.

Key Takeaways

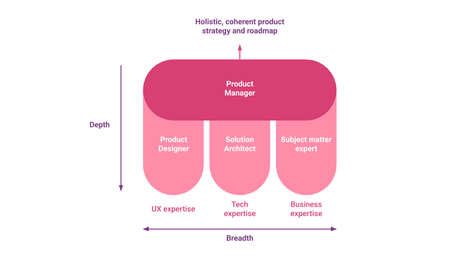

- The Product Manager role is generalist, and therefore faces challenges of processing lots of different types of information and using it for decision making.

- A cognitive bias is a systematic error in the way that you understand and use information, and can be dangerous for Product Managers in particular.

- ‘Rose-tinted spectacle’ biases show that unconsciously, we are trying to construct a narrative which how we’d like the world to be. You need to actively hold a devil’s advocate position to adjust your frame of reference. Step out of your shoes and into those of someone else.

- If you are debating a product decision in a group, especially with stakeholders who are not as close to the product process, it’s very easy for ideas which may not necessarily be the best options to rise to the top through repetition. Use rules and principles for UX, tech and business as part of a product strategy to guard against this.

- Information does not exist in a vacuum and is always influenced by what is presented before, after and around it. The ability to argue from first principles is the foundation of critical thinking and helps root decisions in facts.

- The most important tool for a product manager to have for preventing against all of the cognitive biases outlined in this article is a sound product strategy

Indlægget How To Think Like a Product Manager: Overcoming Cognitive Bias blev først udgivet på Nodes UK.