photo: Morris Engel, Dock Workers 1947 (link)

photo: Morris Engel, Dock Workers 1947 (link)The topic of how actors arrive at their choices and behavior has come up a number of times here. The rational choice model has been considered (link), and other, more pragmatist approaches to agency have been considered as well (link). Finally, a number of posts have considered the idea of character as a key determinant of action (link).

A team of distinguished experimental economists have recently provided a different perspective from any of these on the subject of agency and action. Alain Cohn, Ernst Fehr, and Michel André Maréchal recently published a provocative piece in Nature that appears to show that a certain segment of white-collar professionals (bankers) make very different decisions about their actions depending on the “frame” within which they deliberate (link). If they are thinking within the everyday frame of personal life and leisure, their actions are as honest as anyone else’s. But if they are prompted to think within the frame of their professional environment, their actions become substantially less honest. That professional environment is the large international bank.

Here is the abstract to their paper in Nature:

Trust in others’ honesty is a key component of the long-term performance of firms, industries, and even whole countries. However, in recent years, numerous scandals involving fraud have undermined confidence in the financial industry. Contemporary commentators have attributed these scandals to the financial sector’s business culture, but no scientific evidence supports this claim. Here we show that employees of a large, international bank behave, on average, honestly in a control condition. However, when their professional identity as bank employees is rendered salient, a significant proportion of them become dishonest. This effect is specific to bank employees because control experiments with employees from other industries and with students show that they do not become more dishonest when their professional identity or bank-related items are rendered salient. Our results thus suggest that the prevailing business culture in the banking industry weakens and undermines the honesty norm, implying that measures to re-establish an honest culture are very important.Their research is an exercise within experimental economics. The methodology and findings are described in a brief article in Science Daily (link):

The scientists recruited approximately 200 bank employees, 128 from a large international bank and 80 from other banks. Each person was then randomly assigned to one of two experimental conditions. In the experimental group, the participants were reminded of their occupational role and the associated behavioral norms with appropriate questions. In contrast, the subjects in the control group were reminded of their non-occupational role in their leisure time and the associated norms. Subsequently, all participants completed a task that would allow them to increase their income by up to two hundred US dollars if they behaved dishonestly. The result was that bank employees in the experimental group, where their occupational role in the banking sector was made salient, behaved significantly more dishonestly.

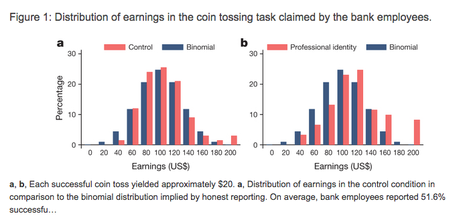

A very similar study was then conducted with employees from various other industries. In this case as well, either the employees' occupational roles or those associated with leisure time were activated. Unlike the bankers, however, the employees in these other industries were not more dishonest when reminded of their occupational role. "Our results suggest that the social norms in the banking sector tend to be more lenient towards dishonest behavior and thus contribute to the reputational loss in the industry," says Michel Maréchal, Professor for Experimental Economic Research at the University of Zurich.The test activity is a self-reported series of coin flips. Participants are asked to flip a coin a number of times and are informed that if they report more successes than average for the group, they will receive a cash reward. Here are graphs that capture the central findings of the study:

The left panel represents the distribution of successful coin tosses reported by the control group, while the right panel reports the average number of successes reported by bank employees in bank-salient conditions. The right panel is visibly skewed to the right in comparison to the control group, which indicates that individuals in the professional-identity group misrepresented their success rate more frequently than the control group. They were less honest within the terms of the experiment.

This is a striking set of findings for a number of reasons. First, it strongly suggests that there are strong markers and incentives within the social environment of the bank that lead its employees to behave in dishonest ways. There is something about working in and around a financial institution that appears to provoke dishonesty. This sounds like a "culture of workplace" kind of effect. It suggests perhaps that bankers are acculturated over an extended period of experience to possess traits of character and behavior that lead them to behave dishonestly.

But second, the data seem to refute the "culture and character" interpretation. The same set of experiments supports the finding that when these same individuals approach the coin-tossing task with a mental framework oriented towards everyday personal life, their choices revert to the generally honest behavior of the broader population. In other words, these findings do not support the idea that banking either recruits or creates dishonest people. Rather, the findings seem to imply that banking encourages dishonest behavior within the specific framework of banking business and only while the workplace signals are salient.

This research has gained broad exposure in the past several weeks because of its possible relevance to the past thirty years of bank fraud and financial crisis that we have experienced. But really it seems more interesting for the theoretical insight it provides into the difficult topic of agency: how do people think about the practical issues that confront them? How do they decide what to do?

These findings suggest that we should explore further the notion that actors possess distinct mental frames that they can take up or put aside readily, and that lead to very different kinds of behavior when confronting the same kinds of problems. Further, we should consider the possibility that these frames are highly portable and contingent: the actor can be led to choose one frame or the other, with important behavioral consequences. This finding seems to point in the same direction as ideas advanced by Kahneman and Tversky in much of their work together, including Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases.

(I chose the photo of dock workers above to raise the idea that workplaces may have many different configurations of behavior that they create through signals and incentives. This may serve once again to suggest that Cohn, Fehr and Marechal's work may lead some researchers to examine other workplaces as well. Are policemen incentivized towards aggressiveness? Are dock workers incentivized towards solidarity? Are doctors incentivized towards interpersonal insensitivity?)