More than 800 years ago, around 1195, Gervase, a monk based in Canterbury Cathedral, recorded in his chronicles a series of reflections on natural, mostly celestial phenomena. In this he was far from unusual. Medieval monastic thinkers often recorded celestial events such as eclipses.

Most medieval observations of the heavens were made by eye. If chroniclers did not observe the event themselves, they would rely on eyewitnesses or other written documents for details.

Technologies such as the astrolabe - an early instrument for mapping the stars - were common in medieval Europe from the 12th century, and known much earlier in the Islamic regions (under the influence of Islamic civilization). Although the early celestial chroniclers of Europe also used astronomical models translated from Greek and Arabic into Latin, they did not have telescopes or any of the other technology that people have access to today.

Gervase lived in a world where nature was believed to be closely linked to human activity. The ancient and medieval universe placed the Earth at the center of the universe, with a series of spheres surrounding it, split into two zones.

Under the moon were these spheres of the elements: earth and water, air, fire. Above the moon came the spheres of the planets: Mercury, Venus, the sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn and then the stars, fixed in their constellations.

In the context of a universe of spheres, ancient and medieval thinkers all worked on the principle that what is above influences what is below. It is important to realize that this explains the serious attention paid to astrology in ancient and medieval thought. Planets, they believed, had effects on the human world. Natural phenomena were connected in this way and integral to understanding that world.

Astronomy, and the related discipline of astrology, had direct practical applications in human activities at the time, from religious study of the calendar and events to medicine and agriculture. The wide utility of astronomy in determining the timing of medical procedures or weather was widely recognized. Philosopher and scientist Robert Grosseteste (c.1170-1253) explained this in his Treatise on the Liberal Arts (c.1200):

The story continues

When planting, the waxing moon is in the eastern quarter or midheaven and is in aspect to the fortunate planets... it will powerfully move the vital heat in the plant and accelerate and strengthen its growth and fruiting.

According to Gervase, the purpose of writing a chronicle was to record the deeds of kings and princes, and to record miracles and omens. Direct correlations were then made by chroniclers of the period between celestial phenomena and political changes - bearing in mind that most, if not all, of the chronicles were written after the fact. The Melrose Chronicle, compiled in the 13th century, notes that:

A comet is a star that is not always visible, but appears most often at the death of a king or the destruction of a kingdom. When it appears with a crown of shining rays, it portends the death of a king; but if it has wavy hair and sheds it, as it were, it denotes the ruin of the country.

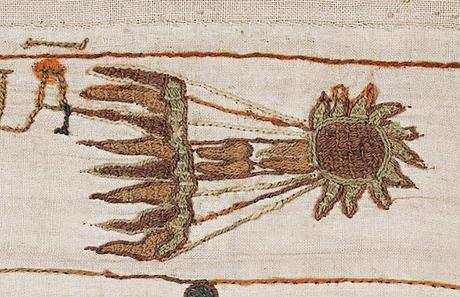

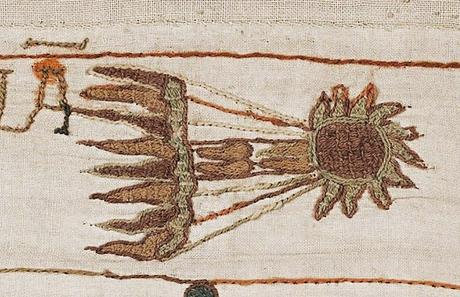

A famous example is the appearance of Halley's Comet in 1066, which was associated by contemporaries with the change of regime in England: from Harald Godwinson to William the Conqueror, who took power after the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

One of the striking things about Gervase is how accurate his descriptions of natural phenomena were, especially those that he believed were beyond comprehension. An example is his account of what can now be identified as ball lightning.

Another example, from September 13, 1178, involves the observation of the "horns" of the partially eclipsed Sun rotating to point toward Earth. Gervase says he was an eyewitness to this eclipse.

Viewers of the April 8, 2024 solar eclipse in San Diego, California, will be able to see something very similar to the observation Gervase described, with the sun's horns rotating and pointing vertically downward. Modeling helps us predict that San Diego's view of the moon will be very close to Gervase's, due to its precise position and timing. Elsewhere in the US, the view of the eclipse will be slightly different.

Also in 1178, Gervase records in similar detail how the image of the moon was split in two by witnesses who reported this to him. Our analysis suggests that this was probably the result of it being seen through a column of hot air. And Gervase wasn't the only one to explain this. The English Benedictine monk Matthew Paris described a spectacular display of halos around the sun in 1233:

These suns presented a wonderful spectacle, and were seen by more than a thousand meritorious persons; and some of them, in commemoration of this extraordinary phenomenon, painted suns and rings of different colors on parchment, so that such an unusual phenomenon would not escape from the memory of man. This was followed in the same year by a cruel war and terrible bloodshed in those counties, and general disturbances took place throughout England, Wales, and Ireland.

Today's celestial spectacles

Today, celestial spectacles are seen as mere manifestations of the richness of a natural world that is, at least in principle, explainable.

Nevertheless, despite the predictive success of, for example, gravitational theory and classical dynamics, there are still problems that remain unpredictable. Some can be deceptively simple - for example the double pendulum or Rott's pendulum (a pair of pendulums forming a "chaotic" system, the motion of which cannot be predicted mathematically).

Others include meteorological phenomena and weather forecasts - and here we find ourselves in many ways in a similar position to medieval chroniclers.

For example, in long-term weather forecasting, we can observe, but are still unable to accurately predict precise future outcomes, such as extreme weather. The medieval chroniclers saw miracles in heaven as omens. It could serve us well to relearn why, and to develop our own perspectives on the interconnections of things.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.