What that camera allowed me to do was to connect my intellectual world to Jersey City itself. It’s not merely that Jersey City is where I live and so where I conduct that intellectual activity, but that Jersey City itself became the subject of that intellectual activity. And more.

It’s 2004 and I return from my conference in Chicago with a camera full of photographs of Millennium Park. I turned them into an online exhibit that my friend (and one-time teacher) Bruce Jackson put online as a working paper. And I shelved the camera. Except every now and then I’d get it out and walk around taking photos, mostly of this and that.

In the Fall of 2006 I decided to photograph signs: street signs, billboards, signs on cars, storefronts, and, of course, graffiti tags, which were plentiful.

I decided they might be particularly interesting. After all, this mural was just across the street from my apartment:

What if there were more like that?

I went looking. And on October 25, 2006, I spotted this:

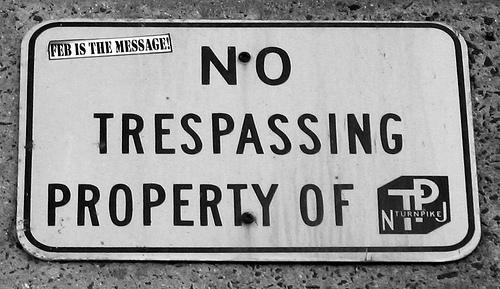

I wonder what’s back THERE? said I to myself. I had to find out. And to do that I had to get to the other side of a chain link fence that had “No Trespassing” signs on it. That’s two problems: Do I decide to trespass? And, if so, just how do it do it, how do I get to the other side of that fence.

The second problem was easier than the first, and the first wasn’t difficult. Trespassing onto THAT land just isn’t that big of a deal. So I crawled through a hole in the fence¬–I later found and opening that didn’t require crawling–and headed toward the graffiti.

Paydirt!

It was one burner after another. I felt like I was in some wacked out Egyptian temple decorated by a tribe of acid heads. And then I saw this:

Game over! I was hooked. I felt like I’d stumbled onto the remains of a lost civilization. I had to investigate.

I cruised the web for information on graffiti and bought myself a single-lens reflex camera. I also decided that I’d confine my research to sites within walking distance of my apartment (in the Hamilton Park area of Jersey City). Sure, there’s all that graffiti over there in New York City. But the City’s already crawling with photographers flicking that graff. It doesn’t need my attention. But who’s interesting in this Jersey City graff? Besides, getting to the City is a bit of a hassle. Not a big hassle, mind you, but enough that I wouldn’t just pick up my camera and shoot some graff on a whim.

With my range confined to walking distance it was no hassle to go out shooting several times a week. That means I’d be able to photograph the graffiti at different times of day, in different lighting and, above all, follow the walls as the graffiti changed. For the first two years or so I even recorded field notes after each run.

I wrote blog posts about it and corresponded with people. I’d chat with the graffiti writers who commented on the photos I’d post to Flickr, and they helped me with identifications. In sum, I’d incorporated graffiti into my intellectual life.

I’d written and published about literature and music. Now I’d turned to the visual arts, graffiti, and to primary research. My work on literature and music had all been analysis and theorizing. I hadn’t done any primary research, no sleuthing in libraries for old manuscripts, no recording musical performances in the Appalachians. But photographing graffiti, that’s primary research, that’s documentation.

Jersey City was beginning to feel like home.

And then the dozers and the pile drivers came. One of my favorite sites was being destroyed:

Obviously, there was nothing I could do to save the graffiti. It was gone. Anyhow, I had a pretty decent photographic record of what was up on that wall, the so-called Newport Wall—which I subsequently learned was important enough to make it into The History of American Graffiti. But it seemed to me that somehow that work should be publicly acknowledged.

Yeah, I know, it’s graffiti. But it’s good stuff. I figured the neighborhood ought to show a little respect.

So I decided to attend a meeting of the Hamilton Park Neighborhood Association (aka HPNA) and see if something could be arranged. At an appropriate point in the meeting I brought up that graffiti up on the embankment. As soon as I’d done that whoever was leading the meeting asked if I wanted it removed.

!@#! Reset! Does NOT compute!

I rethought that one real quick. Clearly whatever vague notions I had to honoring those writers were going to get nowhere. I forget just how I covered my tracks. But cover them I did.

And I became active in the HPNA. Who’d a thought? Me, active in a neighborhood association. Smells like home.

Now, all I have to do is get Steve Fulop elected and I can end this essay. But that’s going to have to wait for another post. But I’ll give you a hint: I has to do with graffiti.

* * * * *

Um, err, for those of you who’ve tuned in late. I didn’t really get Fulop elected. That’s just a hook I stuck up there in the title to get your attention. I explained that at the beginning of the first essay. Now go back and read it.