One of the first items to run on the Invisible Bordeaux blog after its launch eight years ago was focused on the bust portraying the Haitian leader Toussaint Louverture, to be seen on the right-bank waterfront in Bordeaux. At the time, the sculpture was one of the only visible acknowledgements in the public domain of the city’s slave trade past. But times have changed and today there are further signs that Bordeaux is becoming more open about its inconvenient legacy.

For, yes, between 1672 and 1837, ships departed from Bordeaux on the first legs of around 500 triangular slave trade voyages that resulted in 150,000 – possibly more – Africans being deported to the Americas. Bordeaux was not alone. In France - which ranked alongside Spain behind Great Britain and Portugal in terms of the scale of its slave trade - the city of Nantes organized 1,744 expeditions, and the ports of La Rochelle and Le Havre were on a par with Bordeaux.

Before the triangular voyages began (they peaked in the 1780s), the boats departing from Bordeaux conducted straightforward two-way commerce with the Caribbean. Boats would carry wine, oil and flour, all of which would be exchanged for local produce. With the onset of triangular trade, vessels would leave from Bordeaux loaded with foodstuffs, cloth, arms and trinkets which, upon arrival on the eastern coast of Africa six to eight weeks later (the “outward passage”) would be exchanged for slaves. The dangerous middle passage would then follow, with the slaves being ferried in inhumane conditions to the colonies, mainly Saint-Domingue (now known at Haiti) as far as the Bordeaux ships were concerned. The death rate on board the boats was between 10 and 20 per cent.

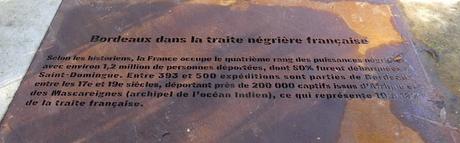

Ground-level panel recently installed on square Toussaint-Louverture.

Upon arrival, the (surviving) slaves would be sold or auctioned off and set to work on the plantations where the average life expectancy was a lowly five to six years. Meanwhile, the boats would embark on their return passage to Bordeaux carrying sugar, cocoa, tobacco, cotton and other produce, making a substantial contribution to the city’s wealth.Until the mid-1990s, this chapter in the city’s history was more often than not glossed over, but around the turn of the millennium Bordeaux took its first tentative steps to bring the subject out into the open. In 2006, then-mayor Hugues Martin inaugurated a ground-level plaque on the waterfront opposite the Bourse Maritime building, and in 2009 came a dedicated section within the permanent exhibition at the Musée d’Aquitaine. As for the Toussaint Louverture bust, sculpted by Haitian artist Ludovic Booz (who died in 2015), it was donated to the city by the Republic of Haiti in 2005.

Returning to the spot today, I note that what had previously been a lone, isolated plinth and its bust are now surrounded by a landscaped area that makes the (refurbished) statue more prominent. Interestingly, the design of the “square” is in fact in the shape of a triangle, no doubt in reference to the triangular trade routes. On the ground, information panels explain who Toussaint Louverture was and his connection with the city (as detailed in the previous Invisible Bordeaux item) and provide a brief overview of Bordeaux’s role in France’s slave trade history.

The triangular square.

Meanwhile, on the left-bank quayside, the barely-visible plaque was replaced in 2019 by a poignant statue created by another Haitian sculptor, Filipo (full name: Woodly Caymitte), which depicts the slave Modeste Testas. The accompanying information panel explains who she was: born Al Pouessi in East Africa in 1765 and captured when she was young, she was bought around 1780 by two Bordeaux brothers, Pierre and François Testas, who owned a business in the city and a plantation in Saint-Domingue.

Pouessi was deported and worked on the plantation, going on to become the slave and concubine of owner François Testas, who gave her the name Marthe Adélaïde Modeste Testas. After François died, she was set free (as symbolized by the broken chains at the feet of the statue) and he bequeathed her 51 acres of land. She married a fellow former slave and died in 1870 aged 105. In the following years, her grandson François Denys Légitime became president of Haiti.

Then, the latest addition to the Bordeaux landscape came in December 2019 to mark the International Day for the Abolition of Slavery, in the shape of "Strange Fruit", a tree-like sculpture by the Réunionnaise artist Sandrine Plante-Rougeol. The tree’s three branches also echo back to the “triangular” notion, and each carries a wine barrel hoop containing a man’s head. Their faces have been blindfolded to suggest a lack of identity, and they reportedly symbolize fear, pain and abandonment.

That same December day, the city announced that explanatory panels were being affixed on streets which had been given the names that harked back to shipowners, traders and sailors involved in the slave trade, a compromise response to years of lobbying by various associations (particularly Mémoires et Partages) asking for those street names to be changed. Each panel provides a concise and factual overview of the connection, as researched by teams at the city’s archives department. The initial rollout concerns six streets or squares (see footnote) but, when preparing this item, I headed out to see the various locations and can state that, at the time of writing (February 2020), those panels have yet to be installed.

Street signs awaiting their information panels.

Whatever, the city’s slave trade past is no longer the taboo subject it once was, and it will be interesting to see what further developments occur throughout the 2020s. Will similar moves be observed in the city’s relationship with its Second World War history, Bordeaux’s other great untold story? Only time will tell…> Find them on the Invisible Bordeaux map: Statue of Toussaint Louverture, Quai des Queyries; Statue of Modeste Testas, Quai Louis XVIII; Strange Fruit sculpture, jardin de l'Hôtel de Ville, Bordeaux.

> The first six panels will be affixed alongside the street signs on rue Desse, rue David-Gradis, rue Grammont, passage Feger, cours Journu-Auber and place Mareilhac. > See this Sud Ouest item for the background story and this France Bleu Gironde article to see the plaques (including a misspelt one for rue Grammont).

> Cet article est également disponible en français.