Freshwater blue-green algae blooms are a global phenomenon that can impact people, pets, the environment and the economy. And as weather patterns change, the blooms - which prefer warm, nutrient-rich water - are appearing in areas where they normally don't exist, a researcher says.

While blooms typically occur in shallow waters with temperatures above 20 degrees Celsius in areas with heavy agricultural activity, blooms have been observed more often than previously expected in colder lakes with fewer nutrients, including Lake Superior and Lake Huron, said Mike McKay, director of the University of Windsor's Great Lakes Institute of Environmental Research (GLIER).

LISTEN: Mike McKay Joins Afternoon DriveHowever, the problem cannot be attributed to rising temperatures alone.

"We have seen a higher frequency of extreme rainfall[s]"This causes nutrients that are tied up in the soil around the lake to be washed into the lake, and we have seen blooms in Lake Superior off Thunder Bay over the past decade," McKay said.

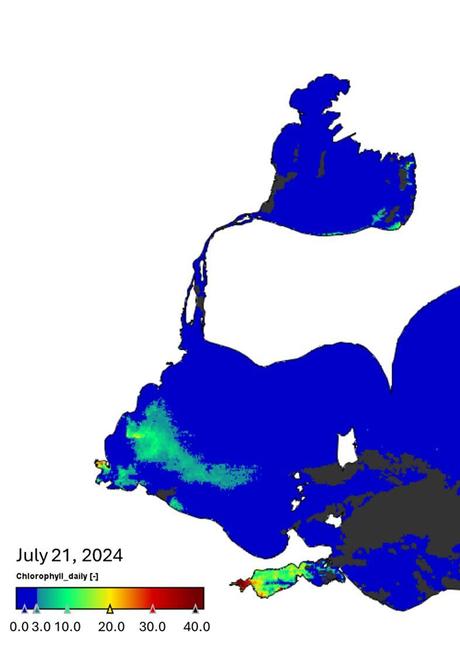

A July 21, 2024, satellite image shows the presence of cyanobacteria in western Lake Erie (bottom half of image), as well as the suspected bloom on the south shore of Lake St. Clair (top half of image). Algal blooms are highlighted in green. (Images from Environment and Climate Change Canada, courtesy of Caren Binding)

"This combination of nutrient loading, either from agriculture or extreme weather events, combined with warming can trigger flowering.

Locations such as Lake St. Clair on the Michigan border and the western shore of Lake Erie in Ohio are often victims of this phenomenon, due to higher surface temperatures and high nutrient inputs.

Earlier this week, the Windsor-Essex County Health Unit warned of an apparent bloom of blue-green algae in Lake St. Clair, located between Lake Erie and Lake Huron in southwestern Ontario.

After checking satellite measurements with both the US National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and Environment Climate Change Canada, McKay confirmed that a layer close to the coast showed signs of cyanobacteria, the microorganisms also known as blue-green algae.

GLIER's Mike McKay recently returned from the Horizons Workshop in Kunming, China, where he discussed algal blooms. (Amy Dodge/CBC)

McKay describes the blooms as "ugly," but also as producers of neurotoxins and hepatotoxins that damage the nervous system and liver if ingested.

Water researchers make trip to ChinaMcKay, along with a group of 24 other scientists from 12 different countries, recently returned from China, honoring his role at GLIER. It's an international relationship that has been building over the past 15 years, with strategies and discussions trying to combat a shared problem: freshwater algae blooms.

"We find them all over the world, it's not just a phenomenon we find in the Great Lakes of North America," McKay said.

Lake St. Clair in southern Ontario is fed by the Thames River and is susceptible to agricultural runoff. (Katerina Georgieva/CBC)

McKay says China has a similar equivalent, the Yunnan Plateau Lakes, located in the southwestern quadrant of the country. According to McKay, algae behave like microscopic plants, present everywhere but not always blooming.

"Think about what you need to grow a plant. Sunlight, carbon dioxide, water and nutrients, [or] fertilizer. So all that is left are the nutrients and we provide those mainly through agricultural activities."

"Some algae are good. They eventually get eaten by other plankton and eventually get absorbed into the food web. These [blue-green algae] are different. They float and form foam on the surface of the water. They also often form toxins that can be harmful to humans."

Blue-green algae stink, contain toxins and suffocate life in the lake. (Courtesy of Essex Region Conservation Authority)

The Ontario government advises that when blue-green algae is found, "you should assume that toxins are present."

"I'm not worried about [drinking water] because our municipal utilities are very good at removing these contaminants. Most people don't want to swim in green water either. But there are recognized risks that vary depending on the exposure," McKay said.

Groups like GLIER may be more concerned about the environmental impact. When a blue-green algae bloom dies, the decomposed biomass creates "dead zones" in the lake, which depletes oxygen levels. McKay says pets are also attracted to the leftover "dried mats" of the dead organisms, which still contain toxins and can lead to death if consumed.

Currently, mitigation efforts depend on the size of the affected lake. According to McKay, smaller lakes can have blooms that have been treated with interventions such as hydrogen peroxide, which can kill the bacteria.

On larger lakes, such as Lake St. Clair or Lake Erie, the treatment is not effective.

Lakes further north, such as Commanda Lake near Sudbury, are seeing more blue-green algae blooms than previously observed due to changing weather patterns. (Shirley Smith-Wilson)

"[Instead]We need to work more with the farming community to identify best management practices so that we have less fertilizer leaking into the lakes. For something like Lake Erie, we need to reduce the nutrient inputs."

As discussions continue, McKay also hopes to highlight the potential socioeconomic impacts and investigate the potential dangers aerosols pose to people living near areas of algal blooms.

"[Increased blooms could] result in reduced recreational opportunities for fishermen, which leads to lower property values and less tourism. And what is emerging now is the question of whether people living in coastal areas are more exposed to airborne toxins."