This is a personal travel story about how a simple omelet showed me a fundamental truth of life. It all began quite accidentally when, after a tasting up valley, we decided go back down to the central square of Sonoma for lunch.

Sonoma is a place of Spanish and Mexican history (a 19th century Catholic mission is there), and a place of early California history too (it was the center of a rebellion by American settlers against Mexican rule that ultimately led to statehood). Today Sonoma Plaza is a dining-and-drinking hub of California wine country, and this was where we came to have lunch, at a casual French bistro just off the plaza called the Girl and the Fig.

We had never been there before and none of this was planned. We just happened to go there, on a whim. Serendipity was our guide, the best guide of all.

We started with some wine and a creamy liver mousse pate—

—and my wife ordered the pork belly tartine.

Not sure what I was in the mood for, I decided, what the hell, to have an omelet. It was under the “Petits Plats & Sandwiches” section of the menu, cost $12, and came with a salad. Corn and fresh red peppers were inside with aged farmhouse cheddar. Sounds good, bring it on.

But, to tell the truth, the first few bites left me perplexed. It was different than what I expected and not the way I liked my omelettes. But the taste of it steadily won me over. The eggs were fresher than what we bought at our local grocery and the entire thing seemed almost—here’s a word you do not commonly associate with omelettes—ethereal.

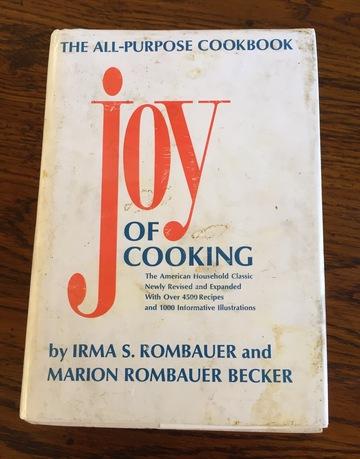

Over the next few days I kept thinking about that omelet and how it tasted and it led me to do something I very rarely ever do: open up a cookbook. The cookbook was my wife’s well-worn copy of Joy of Cooking—

Turning to page 226—32nd printing, 1983 edition—I found the section on egg dishes, and this was the first thing that struck me: there is more than one way to spell “omelet.” That was how they spelled it in the book. I also learned there are two major schools, French and American, on how to make one. As it reads,

“The name ‘omelet’ is loosely applied to many kinds of egg dishes. In America, you often get a great, puffy, soufflé-like, rather dry dish in which the egg whites have been beaten separately and folded into the yolks. In France an entire mystique surrounds a simple process in which the yolks and whites are combined as unobtrusively as possible to avoid incorporating air, and this marbleized mixture is quickly turned into a two fold miracle.”

This was another revelation. All my life I have made and enjoyed American-style omelettes containing ham, bell peppers, mushrooms, avocados, and cheese. Who knew another way even existed? Not me. The omelet at the Girl and the Fig had some American elements but clearly it drew its inspiration from the French.

Now I decided to see if I could make an omelet the way the French did it.

I reread the passage in Joy of Cooking and shared my new-found interest with my wife, who showed me a YouTube video of Julia Child making an omelet on “The French Chef” years ago. This was pure delight, not only watching how she did it—cracking two eggs in a bowl at the same time, whisking them gently, bringing the pan up to heat, not scrimping on the butter, pouring the mixture in and hearing that satisfying sizzle on the pan—but the way she did it, how much she enjoyed it. She was a bright light, that woman.

Then we watched a similar how-to video by another congenial culinary bright light, Jacques Pepin, who shared his wisdom on the American versus French style of omelet. “One is not better than the other,” he said in his enchanting French accent, “it is just different.”

Thus inspired, I gave it a go, cracking the two eggs in a bowl same as Julia had done and whisking them lightly—not beating them, as she had warned against. I added salt and pepper, a splash of water, and some fresh parsley my wife keeps in a container in the freezer. That was it, the all of it. Not a bit of ham or cheese to be found anywhere.

We did not have the precise pan recommended by Julia, so I made do with what we had and made fast work of it. Speed and a hot pan are of the essence in a French omelet and when the eggs were done to my liking—you don’t want to overcook it—I took the pan by the handle and flipped it onto my plate in the style of the French masters. Voila!

Actually the omelet flopped more than it flipped and I have a ways to go before my pan-to-plate technique is perfected. Still, it tasted really good. Not a two-fold miracle but really good. I made one for my wife and she liked hers too and now incorporates this technique into her cooking repertoire. We have since taught the technique to our sons and now they know how to do it.

Since learning how to do it the French way, in fact, I have yet to go back to the American. This is now the way I make my omelettes, channeling as best I can the spirit of Julia. Which is not a criticism of the American school or of the way I always ate omelettes up to this point. I still love American-style omelettes. To echo Jacques Pepin, they are both good—French and American.

But the experience reaffirmed, for me, a truth: that old habits and ways, as comforting and pleasant as they are at times, can after a while turn into a trap, a trap we may not even realize we’re in. You can avoid the trap by wandering around a little, following a whim and seeing where it leads. You may discover there are other ways to cook an omelet. Or omelet.

Kevin Nelson is an award-winning author who blogs at WineTravel Adventure.