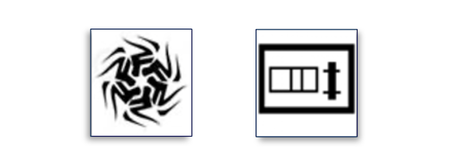

Your spacecraft is going out of control and you will hit planet Arakis unless you turn on the thermal boosters. Which of the two buttons below allows you to activate the boosters in time? Would you have a better chance of surviving if the cockpit designer had installed the left or right button?

If you chose the left button, congratulations! Science suggests you may have just survived the crash landing. But what is it about these buttons that made you choose one over the other?

The short answer is beauty, where the button on the left is more aesthetically pleasing than the one on the right, making us more likely to recognize it. That may seem surprising. But beauty is more important to us than we often realize. As the poet John Keats put it: 'Beauty is truth, truth is beauty. That's all you know on earth and all you need to know.'

How much we like something and how beautiful we find it can have a compelling influence on our experience and behavior. Research shows that when we see beautiful things - whether it's a person, a painting or a kettle - we attribute a whole range of positive feelings to it, such as truth, innocence and efficiency.

Beauty arises from various qualities of the loved thing. Of course, while there is a degree of subjectivity in what we like - I may like something you don't - but when it comes to beauty, there are some established qualities that matter.

This includes certain properties of the object itself, such as proportions, symmetry and curvature, but also the relationship between the object and the viewer, including the degree of familiarity.

For example, we tend to like classical architecture like the Parthenon because of its attractive proportions (like the golden ratio), and we tend to like paintings with familiar motifs more beautiful than those with unknown ones.

A widely accepted principle that explains what we like is the theory of processing fluency: the easier it is to understand something, the more we like it.

Aesthetics are important

But why worry about beauty? Why not take a utilitarian approach and embrace the functional above all else? Simply put, aesthetics matter, and it shows in our behavior and performance.

We surround ourselves with things we like, objects that are appealing to the eye. We visit art galleries and view beautiful paintings. At home we surround ourselves with nice things.

We also tend to persevere more with things we enjoy. An example of this is mathematics, where an elegant and beautiful equation is preferable to a clumsy one. We tend to think that pretty things will work better and be easier to learn and use. And sometimes we're right - like when we reach for a simple pencil sharpener because we think it will work better than a more cumbersome design.

But aesthetics can also influence performance in tasks where efficiency (speed and accuracy) is important. Even if we are not aware of it. In my own research, my colleague and I asked participants in our lab to find icons on a screen. After controlling for several variables - such as complexity, meaning, familiarity and concreteness - we found that participants noticed attractive icons more quickly than their less attractive counterparts.

But this was only if the task was difficult. That is, if the icons were complex, abstract, or unfamiliar, there was a clear advantage for the more aesthetically pleasing targets. In contrast, when the icons were visually simple, concrete, or familiar, the aesthetic appeal no longer mattered-the task was simple enough.

In the figure above, both spaceship booster icons are complex, but the one on the left has greater aesthetic appeal - which is why the left button is better to place in your spaceship.

Aesthetics can beat the blues

Stores often carefully select music, objects and scents that can influence our purchasing behavior. In our recent research we showed how and why this works.

We put participants in a positive or negative mood by listening to a happy or sad piece of music and reading a list of statements. We then asked them to perform a timed search task. Previous research shows that negative moods can negatively affect our performance.

People in a positive mood found the attractive icons more easily than the unattractive icons. However, this benefit also emerged for participants in a negative mood, but slightly later. We concluded that the attractive stimuli must be inherently rewarding, with aesthetic appeal helping to overcome the deleterious effects of negative mood on performance - that is, attraction can beat the blues.

It seems that a positive mood makes us more likely to engage in beautiful things. But even in a negative mood, attractive items are likely to attract attention and influence behavior - as long as we are exposed to them long enough.

There is growing evidence that small doses of psychedelics in a controlled environment, such as a clinic, can help treat depression. Such drugs usually induce intense experiences of beauty - in terms of colors and shapes - and help us feel more at one with our environment.

Small but significant effect

Aesthetic appeal can shorten a participant's reaction time by about a tenth of a second. This may seem small, but it can be quite significant: savings of even a few milliseconds at a time all add up when you're dealing with a poor Wi-Fi connection or a slow 3G signal on a smartphone.

Visionary leaders and innovators have long had an intuitive understanding of the importance of aesthetic appeal and simplicity in industrial design - perhaps none more so than Apple's founder Steve Jobs, whose dedication to aesthetics and simplicity was legendary.

Unfortunately, it seems that many designers did not follow Jobs' visionary intuition. Perhaps the data collected will finally convince them that design has an important impact on performance.

The next time you design a disruptive mobile app, or even the control center for your spacecraft, remember how important aesthetics and beauty are: it just might save your crash landing.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.