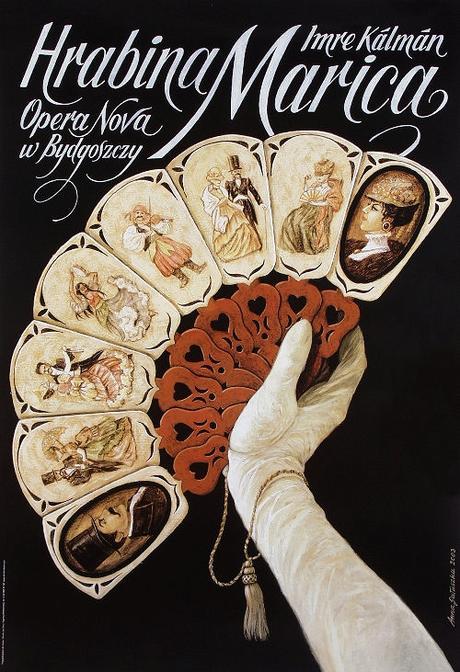

Polish poster for the internationally popular Mariza

This past Thursday, I saw the closing performance of The Countess Maritza at the Ohio Light Opera festival, fortuitously located in my new hometown. (A synopsis of the work, which contains multiple disguises and mistakes in identity, may be found here.) My expectations were confounded on several fronts. The voices of Tanya Roberts, in the title role, and tenor Daniel Neer, as her ill-fated suitor, were welcome new discoveries to me. My impressions of the performance as a whole were conflicting; upon reflection, my predominating reaction is bewilderment. I plan to make a more systematic viewing of the festival next year (I arrived just in time for its final days), in hopes of fathoming its enigmas, for they are many. But of The Countess Maritza: I found it to be a frustrating performance. I would have been better pleased had it evinced less polish, less archness, and more heart.Of the generic scenery I make no complaint. Indeed, a painted backdrop that proclaims, with studied ambiguity, "Central Europe," and a versatile Neoclassical portico that could probably, at need, also be the home of Major-General Stanley or a municipal building in River City argue admirable thrift and resourcefulness in a small company. But the lack of specificity in the performance was another matter. The choreography for the chorus was repetitive, and struck me as stereotypical. The fact that it was the closing matinée may, of course, have done it no favors. The principals, too, were obliged to stand and deliver with depressing regularity. Wide-eyed astonishment or naiveté expressed to the audience is simply not as funny, in such a context, as astonishment and naiveté behind an unbroken fourth wall. Among other things, the English translation by Nigel Douglas doesn't nod towards any mixture of Hungarian and German. It's praised in the program booklet as one of the best libretto translations in the repertoire, and I frankly shudder at the implication. The double entendres were invariably delivered with ponderous deliberateness. I have decided to institute a standard test for all operetta productions I may see in future: do they have at least as much romantic and sexual tension as the classic film of The Sound of Music? The point of comparison was first raised at a Merry Widow performance, which also failed to meet it.

The orchestra -- to its credit -- clearly knew that sexual and dramatic tension were present in the score, and where. The harmonies and dynamics told us as much vividly, but I failed to perceive any corresponding urgency on stage. I would be remiss if I did not mention the dignified and impassioned performance of Alec Norkey as the on-stage violinist. Under the leadership of Wilson Southerland, the orchestra was cohesive, lively, and pleasingly nuanced at critical moments, despite a few issues of stage-pit synchronization. But this musical awareness alone proved insufficient, in my view, to save the dramatic tension.

Despite or because of my incurable romanticism, I became increasingly fretful at the production's failure to suggest the social context which the libretto so insistently invokes. (This is, of course, a problem frequently shared by the Met, as noted here and here.) Class, gender, and ethnicity are all issues touched on by the operetta, and all of these categories of identity were violently unsettled in 1924 Hungary. If they weren't, the plot would not be what it is. And yet. Many questions were left unanswered. Why is Tassilo's friend the baron in uniform, like the puffed-up Prince Popolescu? Are they counterrevolutionaries? Have the gypsies (sic) of Maritza's estate always been there, or are they displaced persons? What is their relationship to the tenants? What are Tassilo's relationships with each of the groups concerned? And what are Maritza's -- does her literal rolling up of sleeves at the conclusion represent a dramatic evolution of character, or a revelation of what has been there all along? Steven Daigle was credited as the stage director, and his list of credentials, on inspection, proved so impressive that I was the more bewildered. I suspected, I confess, that proximity to Gilbert and Sullivan may have rubbed off on this operetta. This is not a gibe at G&S; I'm fond of those Victorian satirists, and I reliably laugh myself silly over their confections. But it seems to me that operetta, however frothy, demands to be taken seriously at a fundamental level. Whatever the ironies and innuendoes, there are always real issues at stake -- or there should be.

Among the singers, matters were considerably more satisfactory, particularly in vocal terms. In speaking roles, Spiro Matsos was sympathetic as the aged servant Tschekko, and Kyle Yampiro (soon to be of the NYC area) made a refreshingly well-calibrated eccentric as Penizek. Light opera would not be what it is without its imperious dowagers, and Julie Wright Costa was genuinely funny — and genuinely touching — as the aged Princess Bozena Cuddenstein zu Chlumetz. Teresa Perrotta played the prophetess Manja as a woman with a self-sufficient detachment that never wavered. Her soprano was interestingly rich, if her enunciation was not always intelligible. I thought something might come of her near-kiss with Maritza -- to paraphrase Oscar Wilde, once might be an accident, but twice looks like intent -- but nothing did. Katherine Corle, as the ingenue Lisa, was a bit off-pitch at the start but settled in nicely. She was, commendably, endearing without being excessively arch, and has a bright soprano that rendered me unsurprised to find Ariadne's Echo in her repertoire.

As Count Zsupán, Grant Knox displayed an impressive and versatile tenor, with more vocal presence and subtlety than the production allowed to his character. In both iterations of his "Varasdin" duet, and in "When I Start Dreaming" ("Ich möchte träumen"), he showed a fine sense of dramatic arc. Sensitivity to text was achieved rather in spite of the libretto. He brought welcome energy, moreover, to "Braunes Mädel von der Puszta" (translated, heaven help us, as "Nut-Brown Maiden From the Prairie.") It was the more a shame, in the view of Knox's fine performance, that the production cast him as a dreadfully camp cross between Anthony Blanche and a candidate rejected by the Drones Club for excessive eccentricity. In his opening scene, he pranced and capered and simpered and I stared in disbelieving dismay. It showcased Knox's energies, certainly, but it seemed a misuse of them.

In the role of the romantic -- not to say quixotic -- Tassilo, baritone Daniel Neer was game but miscast. He never sounded comfortable in the higher reaches of the role, nor in the transition to his falsetto in "Schwesterlein, Schwesterlein." The production gave him no apparent help in creating the character. Neer's Tassilo was earnest and good-natured, but never allowed to be more than curiously passive, drifting among groups on the estate rather than being painfully pulled between them. Tassilo does have a carefully cultivated neutrality of character, arguably... but surely an essential conceit of the drama is that the splendid nullity of the perfect estate manager is something that this fiercely proud young nobleman never quite achieves. Parenthetically, I don't think the production should have had Tassilo and Maritza waltz while carefully at arm's length in Act II; when there is a crucially-positioned waltz -- prickelnde Lust, heißer Glut! -- the participants should surely at some point, no matter the Impossible Obstacles of Class, Etc., get close to each other. Tanya Roberts, happily, was a vivacious and charismatic Maritza, with a rich-toned and agile soprano. I lost some of her consonants, but she was consistently vocally compelling. In her grand entrance -- and the subsequent occasions when she commands the ensemble -- I found it thoroughly credible that she could galvanize those around her. Roberts deserves high praise, in my view, for never flagging in her portrayal of Maritza's indomitable pursuit of self-indulgence... and her equally determined but less self-assured pursuit of Tassilo.

Throughout, indeed, the singers were assured; but the nuances and tensions of Kálmán's work could have been better explored. Since this is operetta, of course, everyone ends up on stage, united for the grand finale. But what has been reconciled, and what overcome? In this production, it wasn't clear.