We all die, just a question of when.

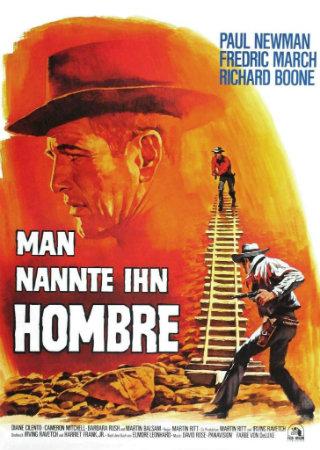

I’m an unashamed fan of westerns from the 1950s, the genre’s golden years, but I’m also pretty fond of those from the following decade. By the end of the 60s, with the spaghetti western in the ascendancy, revisionism was in the air, though that movement wouldn’t come to full fruition until we pass into the 70s. For the classic Hollywood western these were the transitional years, a painful period in some ways, with the genre thrashing about in search of direction. Such times tend to bring about a combination of successes, throwbacks and misfires. When we view the era in this light, I think it’s fair to say that the 1960s was a decade that was simultaneously fascinating and frustrating for western fans. Ultimately, revisionism would strip the genre down to the bone and train a probing searchlight on its innermost workings. One could write an in-depth study on the effects of this process, and I have a hunch the conclusion would be that no genre, least of all one so firmly rooted in myth as the western, could emerge unscathed from such an intimate examination. But I’m not going to take on that task here; instead I’m going to look at one of those late 60s westerns that seemed to benefit from the turmoil of the time, Martin Ritt’s Hombre (1967). Here we have a movie that avoids the outright nihilism of the Euro western, retains the structure and moral complexity of the best 50s efforts, and looks forward to the bleak honesty of revisionism. In short, it becomes a kind of philosophical meditation on social responsibility.

The classic western hero has frequently been characterized as a loner, a man drifting along on the fringes of society for one reason or another. Such a ploy isn’t accidental of course; it allows us to connect with the spirit of freedom and individualism that’s a significant part of the western’s attraction, and also helps objectify the view of society and encroaching civilization. Generally though, the hero does feel himself drawn in some way towards the society he observes. Hombre presents us with John Russell (Paul Newman), a white man raised by the Apache who has categorically rejected the ways of his own race. He’s first seen in his preferred environment, rounding up wild horses, and has clearly been fully integrated into the Apache lifestyle. However, news of an inheritance – a beaten up boarding house – brings him back to white society, at least temporarily. Arriving in town, he’s adopted the outward appearance of his own people but retains the cool detachment of the Apache. Essentially, Russell has made it his business to mind his own business – to have as little contact with the white world he has rejected as possible. He sells up and books passage on the last stagecoach out. Yet, the interrelated nature of society doesn’t really work that way; all action, even calculated inaction, has its consequences. In a sense it’s Russell’s single-minded detachment that lays the groundwork for what follows.The sale of the boarding house, effectively acts as the catalyst that finally pushes at least one man towards crime, and Russell’s own determination to avoid intervention in the affairs of others ensures that a bullying outlaw, Grimes (Richard Boone), gets to ride the stage. The first hour of the film is a fairly sedate affair, concentrating on establishing the character of each passenger and offering some insight into their relationships. Collectively, they add up to a cross-section of frontier types: the outwardly respectable older man and his younger, disillusioned wife, a young couple coming to terms with the realities of married life, the veteran driver who’s long since bid farewell to his ideals, the woman who has been around and remains a survivor, the swaggering bully, and the enigma that is Russell. Locked within the confines of the bumpy stagecoach, the tensions, prejudices and fears of this disparate little group simmers away just below the surface. The pressure comes to a head when they are held up on a remote part of the trail, and the truth about each one emerges. Abandoned in the wilderness, and facing the very real prospect of perishing, they turn towards Russell to guide them out. But Russell is now in something of a quandary; apart from the fact he’d been shunned due to his Apache affiliations, he feels no obligation towards his fellow man anyway. He’s faced with a philosophical dilemma – does he follow his head and leave these people to the fate he reckons they deserve, or does he listen to that still distant voice within that urges empathy.

If we count Hud, then Martin Ritt made three westerns with Paul Newman, and all of them have their points of interest. Adapted from the Elmore Leonard novel of the same name, Hombre is the closest to the traditional western. The basic structure owes much to John Ford’s classic Stagecoach, but it’s a much more cynical affair. The two films do share the vital element of spiritual redemption for their hero, but Ritt’s movie reaches that point in a more tragic and bitter way. The script raises interesting questions about how much we owe others, how far we should go for those we deem undeserving of our sympathy, and whether intervention or isolation is the correct approach. Bearing in mind the film was made while the war in Vietnam was still raging, I think that last issue must have been in the minds of the filmmakers. However, leaving that aside and looking at things from a purely personal perspective, the problems continue to be thorny. Russell not only knows that assisting the abandoned travelers will add to his own peril, but his years living outside of white society have meant that he no longer identifies with these people. Circumstances have resulted in his being caught in a kind of cultural no-mans-land, where his head and heart are in conflict. In cinematic terms, this is a reflection of the position the western itself was facing in 1967, with its soul and conscience pulling in one direction while social and economic factors were pressuring it to go another way. Visually, with the aid of James Wong Howe’s great cinematography and the Arizona landscape, it bears all the hallmarks of the classic western, but the existentialist undertones of its theme point to the future.

Mrs Favor: I can’t imagine eating a dog and not thinking anything of it.

John Russell: You even been hungry, lady? Not just ready for supper. Hungry enough so that your belly swells?

Mrs Favor: I wouldn’t care how hungry I got. I know I wouldn’t eat one of those camp dogs.

John Russell: You’d eat it. You’d fight for the bones, too.

Mrs Favor: Have you ever eaten a dog, Mr. Russell?

John Russell: Eaten one and lived like one.

Paul Newman was an adherent of the method style of acting. Now I’m no fan of the method and the frequently affected performances that it encouraged. I understand it is meant to help the actors dig deeper within themselves and find a truth in their role yet it often seemed to produce the polar opposite, a mannered performance that actually draws attention to itself. Some of Newman’s early roles are badly blighted by this in my opinion. However, by the time he came to Hombre he had moderated his acting style, and what we see on screen is far better, far more involving. As far as I can remember, and it’s been a few years since I read Leonard’s novel, Newman’s portrayal of John Russell is pretty close in spirit to how the character came across on the page. It’s a very quiet performance; I think the stillness of the man, the eternal patience of his Apache side is perfectly captured. There’s a great sense of his being aware of everything, absorbing the sounds, smells and moods around him and storing them away. When he’s aroused to action there’s a jarring abruptness to it that makes it all the more effective. The first instance takes place in a cantina where Russell sits and calmly watches and listens to his Apache companions being goaded by two ignorant redneck types. We’re expecting something, a reaction of some kind, maybe a rebuttal from this soft-spoken man. But the sudden swing of his rifle butt to shatter and drive the splinters of a whiskey glass into the face of the barroom lout is both shocking and satisfying. In a similar vein, the later eruption of aggression when he opens fire on Boone when he comes to parley is made more intense by the apparent calm that precedes it.

Richard Boone’s crafty and cunning Grimes is the ideal foil to Newman’s motionless and emotionless Russell. Boone gave countless performances that were straight out of the top drawer and Grimes has to rank up there among the finest. He had a real knack for conveying a quiet threat – there was always the feeling that here was a man it would be foolish to cross. His first scene in the station when he intimidates a soldier into turning the last ticket available over to him illustrates this quality well. There’s something in that craggy face and low-pitched voice that conveys his intent far more effectively than bluster and showboating; not an easy task but when it works, it works wonderfully. Of the three female roles in the movie, Diane Cilento had the most substantial and the one with the greatest significance. Generally, I feel she was an underrated performer who was always interesting to watch. She played the most down to earth of the three women on that stagecoach, and the one with the lowest social status. Russell’s decision to sell up saw her out of a job and on the streets but with her spirit unbroken. The script offered her several opportunities to shine and she took each one, displaying an earthy and attractive honesty. She was also fortunate to be playing the character whose mentality the average viewer could most readily identify with, providing a kind of bridge between Newman’s omnipotent aloofness and the self-interest of the others.

Fredric March had a nice little late career turn as the corrupt Indian agent, the one whose presence poses the greatest danger to the survival of the group. Basically, he represents all that’s wrong with the society that Russell has rejected – corruption, vanity, weakness and hypocrisy. Still, despite portraying a deeply unpleasant person, March manages to inject a good deal of pathos into his performance and leaves you feeling a little sorry for this man who has transitioned poorly from the successes of his youth; he did something similar in Inherit the Wind, where he tapped into the human frailty of another character who was essentially unsympathetic. Martin Balsam was a first-rate character actor who enriched many a great movie – 12 Angry Men & The Taking of Pelham One Two Three to mention just two – with his everyman persona. As the stagecoach driver who has come to terms with his own limitations and realizes that he can no longer fight the tide of progress, he’s another figure with whom the audience can connect.

As far as I can tell, Hombre has never been released on DVD in the UK, though it is readily available from both the US and continental Europe. I have the Dutch DVD from Fox, which presents the movie most satisfactorily. The film is presented in anamorphic scope and the transfer is very pleasing with good color and definition to show off James Wong Howe’s location photography. The disc offers a wide selection of subtitle options and the only extra feature is the theatrical trailer. For me, Hombre is a highly successful piece of work that hits the mark on a number of levels: as an entertaining western movie, an examination of race and social cohesion, and also contextually, for the position it occupies in the development of the genre. I consider the latter to be the most fascinating aspect, and yet another link between what may superficially appear to be irreconcilable eras. Nevertheless, whatever way one opts to view the film, it makes for a rewarding and thought-provoking experience.