...For the Vive la France Blogathon...

35 years after his death in 1984, François Truffaut is usually remembered as the most successful of the youthful filmmakers to emerge from the nouvelle vague (New Wave) movement that swept French cinema in the late 1950s. But before he would write and direct his first full-length feature in 1959, Truffaut would make his name as an enfant terrible critic at the influential post-war film journal Cahiers du cinema (Notebooks on Cinema). It was Truffaut who authored a famous/infamous January 1954 article, an impassioned and polemic piece, that advanced the “auteur theory.” This theory maintains that auteur films reflect a filmmaker’s personal/artistic vision and possess an identifiable style along with recurring themes and motifs. Alfred Hitchcock, a director revered by Cahiers’ young critics, personified the auteur concept and Truffaut was one especially smitten with his work. He would author 27 articles on Hitchcock over the course of the 1950s.

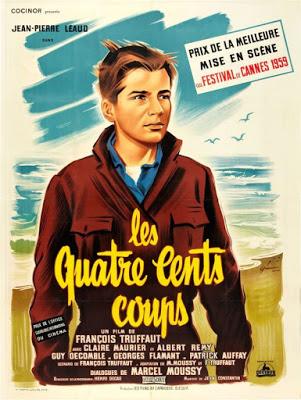

French poster for The 400 Blows (1959)

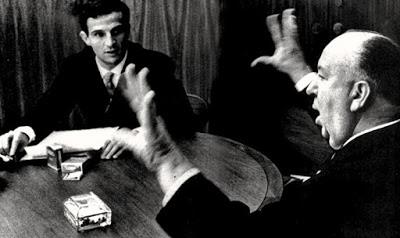

But Truffaut wanted to do more than write about movies and their makers, he wanted to make them himself. His first feature-length film would come with The 400 Blows (1959), an intensely personal film based on his life experience that portrayed circumstances and incidents from his own adolescence. An episodic film of buoyant energy and spontaneity, The 400 Blows would bring Truffaut the Best Director award at Cannes as well as an Academy Award nomination for its screenplay. With this first feature, 27-year-old François Truffaut’s filmmaking career was launched – and so was the French New Wave. Next came Shoot the Piano Player (1960). Based on a pulp novel by David Goodis (Dark Passage), it would be Truffaut’s improvisational, near-zany take on film noir. Truffaut described the film as “a grab bag” “shot without any criteria,” and it seems in retrospect to be his most freewheeling venture. By turns lighthearted, exciting and sad, it recounts the tale of a pianist who finds himself in a dire predicament involving gangsters. After this film’s successful debut, Truffaut undertook a project he’d been wanting to make for years, his adaptation of the novel Jules and Jim. The story is set during the World War I era and follows an unconventional romantic triangle involving two close friends and the beautiful, capricious woman both men love. An entrancing mix of whimsy, tenderness and tragedy, it stars Jeanne Moreau in one of the great performances of her early stardom. These first three films established Truffaut at the forefront of French cinema, but two years would pass before his fourth feature would come.A few months after Jules and Jim’s release early in 1962, Truffaut contacted Alfred Hitchcock and began arrangements for their now world-famous interviews. These conversations would take place at Universal Studios over eight days and countless hours during the summer of 1962, and the two men would discuss in depth each of Hitchcock’s films as well as his cinematic technique and philosophy. Truffaut would have the recordings of their talks transcribed and, once edited, the initial edition of Hitchcock/Truffaut would be published in 1966.

Truffaut and Hitchcock, 1962

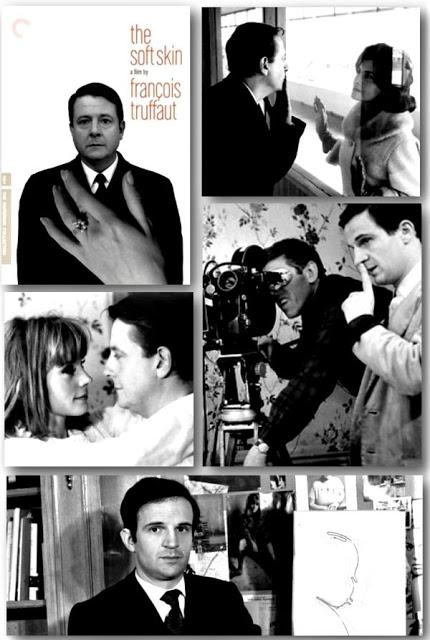

As he set out to make his fourth film, The Soft Skin (1964), Truffaut declared that it would be, “…indecent, completely shameless, rather sad, but very simple.” The idea for the plot would come to him in various forms, including a very recent local news story, “the Nicole Gérard affair,” in which a 41-year-old married woman had taken public revenge on her unfaithful husband. Another inspiration came with a brief incident Truffaut had observed by chance, the sight of a couple kissing in the back seat of a taxi and the sound of their teeth clinking as they kissed. He assumed, taking in the passion of the kiss, that this was an adulterous moment. Further material must also have come from his own life; Truffaut was notoriously and incessantly unfaithful to his wife and they had already separated and reconciled once because of it by the time he began on The Soft Skin.

Jean Desailly and Nelly Benedetti

The storyline concerns middle-aged Pierre (Jean Desailly), a celebrated “literary lion” who is the editor of an academic journal and a sought-after authority on Balzac. Pierre lives in Paris with his stay-at-home wife, Franca (Nelly Benedetti), and their young daughter. On a trip to Lisbon, where he will give a talk to a sold-out crowd on “Balzac and Money,” he has a chance encounter with beautiful young flight attendant, Nicole (Françoise Dorléac), that leads to an intense affair. As Truffaut had planned, the story is simple. But the tale that plays out onscreen is a bit more intricate.In conversation, Truffaut had suggested to Hitchcock the significance of the elements of fear, sex and death in his films. These elements would also surface in The Soft Skin. Despite being a distinguished national figure, Pierre is an anxious, timid man. The film opens with him hurrying to catch a plane to Lisbon, fearful that he will be too late. As he rushes in traffic to Orly, Claudine Bouché’s editing and Georges Delerue’s score accentuate the intensity of Pierre’s agitation, also setting an ongoing undertone of tension. And though Pierre is a subdued character, his wife is a womanly woman, a passionate woman, and it is clear that their marriage is still sexually alive. Pierre’s powerful attraction to and obsession with Nicole imply his underlying carnal nature. And death…well, that will come soon enough.

Françoise Dorléac

Unlike Truffaut’s earlier work, this film’s narrative is entirely linear. Neither does The Soft Skin have the buoyancy or improvisational spirit associated with the first three films. Hitchcock’s stylistic influence can be detected in the film’s visuals, notably the editing, but another aspect that seems distinctly “Hitchcockian” is its cool, detached tone. And there is the obvious contrast between Pierre’s emotionally volatile brunette wife and his poised, near-blonde mistress (Dorléac, who would lighten her hair dramatically for Billion Dollar Brain (1967), might have been an enchanting “Hitchcock blonde” had she lived).As with Truffaut’s previous films, The Soft Skin was shot in black and white and on location. In fact, keeping it personal, he used his own apartment for the scenes set in Pierre and Franca’s home. And as was his way, and in contrast to Hitchcock, he would present his lead characters even-handedly. Pierre is depicted as neither hero nor villain, he isn’t especially sympathetic or unsympathetic. He is a man – not unlike Truffaut himself – who, in this case, has managed to make a mess of his life without realizing it until it’s too late – which he also doesn’t realize.

From its frenetic opening, through its varied domestic and illicit interludes to its climactic finale, The Soft Skin moves deliberately and persistently toward its denouement. In the film’s final shot Nelly Benedetti, as Franca, sits in a café, a small, enigmatic half-smile flickers across her face, her eyes stare blankly. The expression is hard to read but for a fraction of a second we seem to recognize something and, with a start, recall our last glimpse of Norman Bates in Psycho.

~

The Soft Skinwould be the first of four Truffaut “thrillers” – including Fahrenheit 451(1966), The Bride Wore Black (1968) and Mississippi Mermaid (1969) –that have come to be known as “Hitchcockian.”

The Soft Skin is among the five Truffaut films highly recommended by the TSPDT Guide and has been included among the BFI’s list of François Truffaut’s 10 essential films.

~

Click here for links to all Vive la France! participating blogs.