Anti-German sentiment in the United States

When the United States entered World War I on April 6th, 1917, their previous ambivalence towards the war vanished. Germany's campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare, atrocity reports from Belgium and the Zimmermann Telegram, promising Mexico the return of the American Southwest for an alliance, moved Woodrow Wilson and the American public from neutrality to full-fledged commitment on behalf of the Allies. Wilson's perorations that "we must make the world safe for democracy" overcame long-standing reticence towards a conflict that seemed brutal, distant and irrelevant.Along with military enlistments and Red Cross donations, Liberty Bonds and Victory Gardens came the uglier side of patriotism. America's large German population, from assimilated Midwestern farmers and miners to Mennonites and Hutterites, found themselves targets of a campaign of suspicion, intimidation and occasional persecution. Richard Slotkin writes that "any German-American who retained any shred of feeling" for their homeland became "pro-German, anti-American [and] un-American."

In 1918 at least 8,000,000 first- and second-generation Germans lived in the United States. Whereas earlier generations (especially the so-called Forty-Eighters) had been educated and politically active, integrating quickly (if not always easily) into American society, those arriving later in the century tended to be working class Germans who clung to their culture, religion and especially their language. Nonetheless, Frederick Jackson Turner, a renowned historian, praised Germans for possessing "a conservatism and steady persistence and solidarity" that made them ideal Americans.

German immigrants at Ellis Island, 1931 (source)

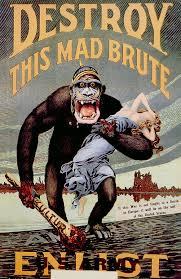

While America thrilled to lurid tales of the "Rape of Belgium," German-Americans were torn between neutrality and outright support of their homeland. The German-language press raised funds for German war wounded and issued editorials praising the Kaiser. Leaders attacked Britsh perfidy and American chauvinism while defending their homeland. "No one will find us prepared to step down to a lesser Kultur," thundered Charles J. Hexamer of the National German-American Alliance in 1915; "we have made it our aim to draw the other up to us."Then America entered the war, and German-Americans went overnight from suspect to enemies. Americans weaned on press reports and British propaganda about the rapacious "Huns" (so-called after Kaiser Wilhelm's boast, during the Boxer Rebellion, that Germany would lay waste to China like the Huns of old) easily shifted to seeing Teutons in their midst as potential enemies. Along with pacifists, socialists and other undesirables, they became targets for discrimination and violence.

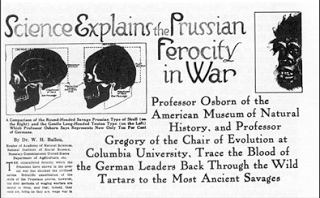

President Wilson proclaimed that "the military masters of Germany have filled our unsuspecting communities with vicious spies and conspirators." Attorney General Thomas Gregory added that America possessed "a very large number of German citizens...(who planned) trouble of a sinister sort." The Godly weighed in: Reverend Newell Dwight Hillis announced that nobody "can serve God and the Allies, Germany and the Devil, at one and the same time". Science (or pseudoscience) agreed, with Professor Henry Fairfield Osborn using eugenics and phrenology to paint Germans as "Wild Tartars" more Asian than white.

Fears of German saboteurs certainly weren't unfounded. Before the United States entered war, intelligence officer Franz von Rintelen established a spy ring that carried out acts of sabotage along the Eastern Seaboard. Their most famous exploit came on July 30th, 1916 when the Black Tom munitions plant in Jersey City, New Jersey exploded. Rintelen claimed many other successes in his memoirs, some unverifiable or improbable (a plot to infect military horses with glanders, which evidently failed). Even so, his agents achieved enough to strike fear into American authorities.

There was also Eric Muenter, a college professor who had changed his name to Frank Holt after murdering his wife in 1906, teaching at Cornell when the war came. In July 1915, he launched a one-man terror campaign which included, within a matter of days, bombing the Capitol building and shooting Jack Morgan, heir to tycoon J.P Morgan, in New York City. Though Muenter (who committed suicide in prison) supposedly had ties to Rintelen's network, he apparently acted on his own volition.

Eric Muenter (left) and Franz von Rintelen

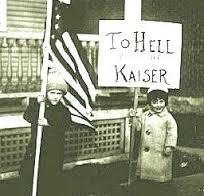

Nonetheless, these cases were extreme, isolated and offered little excuse for the ensuing campaign of hatred. Theodore Ladenburger, a German-born merchant in New York, complained that "from the moment that the United States had declared war on Germany, I was made to feel the pinpricks of an invisible but so much more hurtful and pernicious ostracism as a traitor to my adopted country." Indignities large and small ravaged the German-American community, even as thousands served in the American military or otherwise aided the war effort.Numerous states outlawed teaching German in schools, banned or restricted German language press; Iowa and South Dakota made it illegal even to speak German in public. "If their language is disloyal," one lawmaker reasoned, "they should be imprisoned." Towns and streets of German origin were renamed, as were animals and objects; German shepherds became Alsatians, sauerkraut became liberty cabbage, German measles, liberty measles.

Sometimes, persecution took on comic proportions. Police arrested Lou Derringer, living in Chicago, for teaching his parrot to say "Hoch der Kaiser!" Other incidents were more serious: Germans throughout the country were beaten, tarred and feathered, painted yellow or sprayed with hoses. Mennonites and Hutterites, two pacifist sects, were impressed into military service; two Hutterites imprisoned for refusing to wear uniforms died in Ft. Leavenworth. Even Carl Muck, conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, was banned from playing, then interned as an enemy alien.

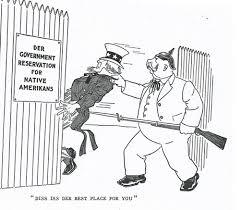

Anti-German cartoon in Life (source)

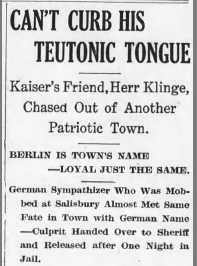

Charles H. Klinge would likely have attracted attention even without wartime hysteria. Born in Pirna, Saxony in the early 1860s, he emigrated to America in his twenties, becoming a citizen and settling in New York. Evidently well-educated (he possessed a Masters in Chemistry), he nonetheless worked as an encyclopedia salesman. At least, that was his day job; Klinge trafficked in illicit side activities, from embezzlement to an unlicensed medical practice to carrying bottled "chemicals" in a black bag. He also indulged in inflammatory pro-German, antiwar remarks that set the Bureau of Investigation on his tail.Tracking him from New York into Pennsylvania, the Bureau caught up with Klinge in Harrisburg in the summer of 1917. Besides receiving a harangue on the glories of kultur, the investigating agent found nothing incriminating and released Klinge. The Bureau continued to track Klinge's movements for months, until the American Protective League (a semiofficial detective agency organized by the Justice Department) informed them that Klinge had enlisted in the Army. But the APL were glorified vigilantes, not policemen; unsurprisingly, they had the wrong Charles Klinge, thirty years younger than the man under investigation.

After several months incognito, Klinge resurfaced in Salisbury, a small mining town in Somerset County, in March 1918 with a suitcase full of encyclopedias. Evidently he was persuasive, as the local school board decided to stock their library with them. While drinking at Hay's Hotel, however, Klinge blurted out odes to the Kaiser while drinking, infuriating local patriots. Though Salisbury's population was overwhelmingly of German descent, they had no tolerance for a loud-mouthed "Kaiser worshiper," least of all an outsider.

Meyersdale Republic, 4/11/18 (source)

Just after midnight on April 1st, about 100 men entered the hotel through a fire escape. Several forced their way into Klinge's bedroom and dragged him, half-dressed, into the street. Someone fitted a dog collar around his neck, and the hapless German was led through the streets of Salisbury, "jeered, kicked and cuffed by the Mob," according to newspaper accounts. He was then forced to kiss an American flag, a favored punishment of wartime super-patriots, then dunked in a water trough for half an hour. Eventually led back to the hotel, he was further assaulted by townspeople before police intervened.Klinge spent the night in jail, indulging an interviewer with another pro-German harangue before leaving town on a trolley. He resurfaced in nearby Berlin a few days later, again enraging townsfolk with pro-German comments. Per the Pittsburgh Press, "a crowd with horsewhips and ropes took him from the hotel and would have handled him roughly had not cooler heads prevailed." Sheriff Wagner escorted him to Somerset, where Klinge spent another night in prison before being released "with a warning to profit by his experiences in Somerset County."

It's unclear what happened to Klinge after this experience; he apparently returned to New York and died in 1923, a strange life reduced to a historical footnote. It's less likely that he was a spy and traitor, as alleged in contemporary coverage, than a loudmouth and possibly a petty criminal. Whatever his sins, Klinge escaped lightly compared to Robert Prager, a man who didn't ask for trouble but paid for his ancestry with his life.

Robert Prager (source)

Born in Dresden around 1886, Prager emigrated in 1905 and drifted across the Midwest. "Limited in intelligence and education," per Frederick C. Luebke, he worked assorted jobs, did jail time for theft in Indiana, then moved to St. Louis, Missouri. Prager established himself there as a hardworking citizen, active in the Odd Fellows and grateful towards his adopted country. When war broke out, Prager attempted to enlist in the Navy but was declined due to poor eyesight.Instead, Prager worked at a coal mine in Maryville, Illinois, a few miles north of St. Louis. His foreign ancestry, stubborn personality and left wing political views marked him for suspicion. Rumors spread that he attempted to purchase dynamite from a local merchant; that he made pro-German and anti-American comments; even that he asked a superintendent about destroying the Maryville mine. On April 3rd, suspicious coworkers ran him out of town, escorting him to nearby Collinsville for his safety.

Urged by friends to accept protective custody with a local Sheriff, Prager instead returned to Maryville, posting documents that proclaimed his innocence and loyalty to the United States around town. He returned to Collinsville, while about 75 of his colleagues stewed at a local bar, puzzling over his defiance of their instructions. Eventually, they decided to teach Prager the ultimate lesson in patriotism.

Now hundreds of townspeople, fortified with liquor and patriotism, swarmed to city hall to glimpse the "German spy" in their midst. They ignored Mayor Siegel's pleas for order and forced their way inside. The townsfolk found Prager hiding in the basement and dragged him into the street, where he repeated the humiliating rituals of flag kissing and singing Hail Columbia. Incredibly, the police made no effort to intervene, merely following the procession from a distance until it left town.

Commandeering an automobile, the mob leaders drove Prager to a farm, intending to tar-and-feather him. They returned to town empty-handed, interrogating the exasperated German about his intentions to bomb the Marysville mine. When Prager proved non-responsive, Joseph Riegel, a local troublemaker recently separated from his wife, grabbed a rope and shouted "Come on fellows, we're all in this! Let's not have any slackers here."

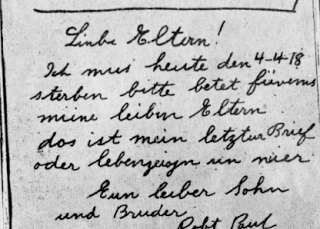

Prager's last letter (source)

Realizing his last moments had come, Prager asked for a pen and wrote to his parents in Dresden. "I must on this fourth day of April, 1918, die. Please pray for me, my dear parents. This is my last letter and testament." He handed the note to Reigel, prayed in German and then walked stoically to a nearby tree. Prager's long night of torment ended as the mob hanged him. His last words were a request to "wrap me in the flag when you bury me."News of the lynching spread throughout the country. Response was mixed: while many condemned vigilante justice ("A fouler wrong could hardly be done America," opined the New York Times), others found it "a healthful and wholesome awakening in the interior of the country" (Washington Post). Others blamed the incident on insufficient sedition laws which forced locals to act; this feeling led to the Sedition Act, with its severe crackdowns on wartime speech. President Wilson offered only a tepid condemnation of "acts of injustice...based upon suspicion to those who do not deserve it."

Despite Illinois Governor Frank O. Lowden's vow to punish Prager's killers, the trial in May 1918 proved a farce. Defense Attorney Thomas Williamson boldly argued that wartime exigencies justified murder, while conflicting witness testimony prevented the court from identifying the killers. The jury acquitted the killers within forty-five minutes, shaking hands with the accused as they exited the courtroom. "I guess nobody can say we aren't loyal now," one jury member exclaimed.

Patriotic killers (source)

After Armistice Day, Wilson continued to attack immigrants, commenting that "any man who carries a hyphen about him carries a dagger which he is ready to plunge into the vitals of the Republic." His administration shifted attention from Germans to Eastern European immigrants, targeting socialists, Wobblies and other dissidents in America's first Red Scare. If anything, this peacetime oppression outpaced the wartime backlash, triggering mass arrests, patriotic killings and wholesale deportations of undesirables. Wilson's behavior set an unpleasant precedent, used in future wars and peacetime alike by unscrupulous politicians and military leaders.As for German-Americans, they reentered the American body politic, reestablishing their reputation as conservative and hardworking while markedly less alien. Frederick Luebke notes that "World War I had the effect of accelerating the assimilation of most German-American groups," with German press and language fading from use, a national identity largely forfeited after their traumatic experiences. Today, barring the occasional Oktoberfest celebration, most German-Americans simply consider themselves Americans, their fractious past largely forgotten.

Sources and Further Reading

Frederick C. Luebke's Bonds of Loyalty: German-Americans in World War I (1974) remains the most comprehensive treatment of this subject. Other sources consulted include David M. Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society (1980); Paul M. Murphy, World War I and the Origin of Civil Liberties in the United States (1979); and Richard Slotkin, Lost Battalions: The Great War and the Crisis of American Nationality (2004). The information on Charles Klinge comes mainly from newspaper accounts and other research I'm preparing for the Somerset Historical Center.