On February 2nd, 1917, a Chicago businessman named Albert M. Briggs arrived at the city's Justice Department. Briggs, the vice president of an advertising agency, was eager to join the coming war with Germany, but was ineligible for military service due to age and infirmity. He tried to persuade Hinton D. Clabaugh, Superintendent of the Chicago office, that he might yet serve his country, at home if not abroad. Why not organize a unit of citizen-detectives to police the home front?

On February 2nd, 1917, a Chicago businessman named Albert M. Briggs arrived at the city's Justice Department. Briggs, the vice president of an advertising agency, was eager to join the coming war with Germany, but was ineligible for military service due to age and infirmity. He tried to persuade Hinton D. Clabaugh, Superintendent of the Chicago office, that he might yet serve his country, at home if not abroad. Why not organize a unit of citizen-detectives to police the home front?To Briggs' surprise, Clabaugh embraced the idea. After receiving the consent of city and state officials, Clabaugh gave Briggs authorization to recruit agents and informants, while providing automobiles to the Justice Department for their own purposes. Over the next month, in consultation with Clabaugh and the Bureau of Investigation, Briggs drafted a formal memo proposing "a volunteer organization to aid the Bureau of Investigation of the Department of Justice" in combating internal subversion. Thus, on March 22, 1917, the American Protective League was born.

To modern minds, this scenario lands somewhere between absurd and chilling. Yet America in 1917 lacked the resources to deal with potential subversion. The Bureau of Investigation, headed by A. Bruce Bielaski, fielded only 219 agents nationwide, with limited powers for arrest and investigation. Few crimes in that era were federalized, leaving the Bureau to investigate cases of fraud and human trafficking. Most suspected that the Secret Service, which spent most of its time tracking counterfeiters (occasionally protecting the President as well), would play the major role in hunting spies and saboteurs.

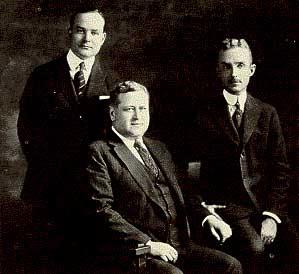

From left to right: Charles Daniel Frey, Albert M. Briggs, Victor Elting

Nor did the idea seem especially outlandish. The country wasn't far removed from the days of Wild West frontier justice and formalized vigilantism, where citizens defended themselves in lieu of government protection (while abusing the privilege in vendettas, prejudice and pettiness). The APL had a close precursor in the Union League, an organization from the Civil War era which rousted Confederate spies and Southern sympathizers in the Midwest. Its name, however, evidently came from an insurance company that Briggs counted among his clients.As America lurched towards war, Briggs used his business contacts to create a national spy network, creating Service Divisions across the country. He enlisted the help of Charles Daniel Frey, a Denver native with a varied background as a journalist, educator and Army Intelligence captain, and Victor Elting, an attorney active in the Chicago social scene and the Republican Party. These three men became the APL's national directors, heading an organization that would soon claim 250,000 operatives.

Their efforts received the approbation of Attorney General Thomas Gregory, who assured a skeptical President Wilson that "it should be encouraged and...not subject to any real criticism." Director Bielaski, eager to expand his agency's power, allowed Briggs to issue APL members quasi-official badges while encouraging his agents to cooperate. With America's entry into the war and the passage of the Espionage Act soon after, it became open season on anyone considered subversive.

Early APL efforts were bumbling, confused, even comical. Detectives posed as Secret Service agents and granted themselves a wide prerogative, attacking and arresting anyone they perceived as enemies or draft dodging "slackers." Their rowdiness became an embarrassment to their government sponsors: Briggs sent out a directive to his office emphasizing that "no captain, lieutenant or operative has the power to arrest," urging them merely to inform, gather information and alert the proper authorities.

Thomas W. Gregory, enabler of vigilantism

If privately exasperated, the Wilson Administration found the APL useful. The President commented that "the German spy system is highly organized and is operating efficiently...I think it ought to be extirpated with a strong hand." Others agreed: Senator Ben Tillman redirected his legendary hatred of Negros towards spies: "I want to see the German devils taken out and hanged!" And Attorney General Gregory said of subversives: "May God have mercy on them, for they need expect none from an outraged people and an avenging government."The APL tackled enemies of all stripes. They harassed German-Americans, attacking them with yellow paint, horsewhips and tar-and-featherings. Young men found themselves accosted by detectives who demanded draft cards or proof of exemption (a practice encouraged by a $50 national bounty on deserters). Eventually they refined their efforts to eavesdropping; the Chicago office enjoyed breaking into suspects' homes and recording their conversations with a phonograph. This backfired on one hapless detective, who somehow recorded himself making love to his mistress in a suspect's apartment.

Less comically, the League battled traditional enemies of the American state. One particular target were the International Workers of the World (IWW), America's most radical labor union, widely believed to be fomenting revolution across the nation. From Philadelphia to Seattle they raided IWW headquarters, siccing the police on public gatherings and occasionally attacking Wobblies themselves. Business leaders and conservatives happily enlisted these patriotic roughnecks to break strikes and retaliate against troublemakers. Indeed, one APL leader boasted that "breaking up the activities of labor agitators and anarchists" was the organization's greatest achievement.

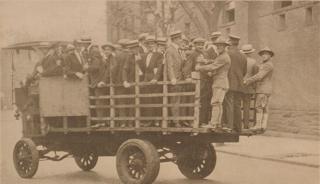

Wobblies arrested at Bisbee

On June 26, 1917 in Bisbee, Arizona, a longstanding dispute between the IWW and the Phelps Dodge Mining Company triggered a massive strike of copper miners. With over 3,000 miners taking part, the strike brought Bisbee to a crawl. Harry Wheeler, Sheriff of Cochise County, requested government assistance, proclaiming the strikers "pro-German and anti-American." Local APL chapters inflamed the situation by filing reports with military intelligence indicating that the Kaiser was indeed bankrolling the Wobblies; an offshoot, the Citizens' Protective League, played the decisive role in crushing the strike.Several weeks later, on July 11, 1917, Sheriff Wheeler organized a posse numbering over 2,000 men which descended on the strikers' camps, arresting some 2,000 men. About 1,300 refused to recant their affiliation with the IWW, after which they were stuffed in filthy cattle cars and transported over 200 miles to Hermanas, New Mexico. They were imprisoned without formal charges, denied water and generally abused, until President Wilson intervened, sending soldiers to establish a camp for the refugees in Columbus, New Mexico.

Bisbee was a curtain-raiser on a wide-ranging campaign against the Wobblies, in which the American Protective League played a major role. APL detectives joined Bureau agents during a coordinated, nationwide mass raid on IWW offices on September 5th, 1917. This led to a mass trial in Chicago, in which Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis convicted 166 Wobblies under the Espionage Act. Which isn't to mention Frank Little, whose antiwar statements and unionist agitation led to his murder by masked killers in Butte, Montana in August 1917.

Wobblies as traitors

In spring 1918, American troops finally arrived in France, just in time to engage in the desperate battles arising from Germany's Spring Offensive. This led to renewed resentment towards "slackers" and draft dodgers who shirked their duty as doughboys bled at Bellau Wood and Chateau-Thierry. The Federal government prepared for a crackdown, with the APL deputized to act alongside local authorities, Bureau agents and even Federal troops. Secretary of War Newton Baker urged that anyone evading the draft should be "promptly brought to trial by court martial."The raids began in Pittsburgh that March and slowly spread across the country, with major assaults occurring in Cleveland, Minneapolis and Chicago. In the latter city, on July 11th, APL detectives proved particularly aggressive, stopping men on the street, intercepting trains and automobiles, even entering private homes. Nearly 150,000 men were questioned, 16,000 arrested and 1,465 convicted of draft evasion or desertion. The Chicago Tribune, at least was pleased, praising the APL for employing "a minimum of friction and a maximum of toughness."

This was merely a curtain-raiser for the APL's biggest operation, in New York City. So far, League activities in that city ran afoul of poor recruitment and red tape, with local authorities reluctant to cooperate. In June, US Marshal Thomas McCarthy disrupted an attempted raid by grabbing an APL detective's badge and releasing the suspects. Attorney General Gregory intervened, and by September the APL was ready to pounce. Charles Frey assured his colleagues that "the Attorney General and Mr. Bielaski are in back of the American Protective League to the limit."

A. Bruce Bielaski

On September 3rd, 1918 hundreds of APL detectives, Bureau agents and soldiers descended upon the city. They blocked off subway cars and streets, raided bars, businesses and theaters, forced men to produce draft cards and registration. Within a few hours they arrested nearly 40,000 men, far more than the raid's headquarters, the 69th Regiment Armory, could hold. Local APL leaders and Bureau agents appealed for National Guard troops to assist but were rebuffed; Federal troops defensively fixed bayonets as friends and family of those apprehended gathered around the armory.The raids dragged on well into the evening, with tens of thousands of men, guarded by a few hundred soldiers, awaiting assessment by local draft officials. Eventually, 300 men were imprisoned in The Tombs for draft evasion, allowing Bureau officials to boast that five percent of their victims were indeed guilty. A second day of raiding nearly yielded violence when Brooklyn commuters resisted arrest efforts; nonetheless, 500 of their number, and 4,000 across New York ended the day in custody.

The New York raids triggered a backlash, leaving the APL's benefactors at a loss to defend themselves. Superintendent DeWoody, the Justice Department official overseeing the raid, passed the buck: "It is silly to assume that I would have ever undertaken such work without the authority of my superiors." Henry Ward Beers, New York's United States Attorney, claimed the APL had no authority to carry out the raids. The New York World excoriated the action as "Amateur Prussianism" and a "wanton ravishing of the very spirit of American institutions."

New York slackers in custody

The APL remained in existence for a few months after Armistice Day. Charles Daniel Frey boasted that "the assistance and information furnished by [the APL] in connection with the registrations and violations of the draft law have alone fully justified its existence," and others hoped that the APL would continue its role in peacetime. Instead, newly-appointed Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer disbanded the organization in the spring of 1919. With the war now concluded, there no longer seemed a need for the League, even as its legacy lingered on.A variety of organizations took up the APL's slack. The American Legion, made up of returning veterans and political conservatives, continued their vendetta against the Wobblies, culminating in the Centralia Massacre of November 1919. William J. Simmons, who organized an Atlanta chapter of the APL, incorporated its tactics of secrecy and political violence into his revived Ku Klux Klan. General Leonard Wood organized the National Security League, which outlasted the APL and survived into the 1942 by shifting from German bashing to Red baiting.

J. Edgar Hoover

Meanwhile, Palmer's initial tolerance dissipated after a series of anarchist bombings, one targeting his own home. Reborn as a Red-baiting authoritarian, Palmer instituted a wide-ranging crackdown using a greatly expanded Bureau of Investigation to arrest and deport radicals. Like the APL, Palmer overreached himself with mass raids against immigrants and socialists in January 1920, which ruined his reputation and stirred public backlash. Yet while Palmer faded into ignominy, the Bureau (and its rising star, J. Edgar Hoover) grew more powerful than ever.As recently as 2002, Attorney General John Ashcroft instituted Operation TIPS, encouraging American citizens to spy and report on neighbors engaging in "suspicious activities." While the program received widespread criticism in press and political corners, vestiges of it remain in nationwide Terrorism Liaison Officers. And myriad other groups and politicians keep the American Protective League's spirit alive, blessing Americans' darkest fears and basest instincts by wrapping them in patriotism. On the downside, few of them have such cool badges.

The most comprehensive source on the American Protective League remains Joan M. Jensen's The Price of Vigilance (1968), which provided the overwhelming majority of material for this article. See also David M. Kennedy's Over Here: The First World War and American Society (1980) and Paul L. Murphy, World War I and the Origin of American Civil Liberties (1979).