While the American Protective League waged war on phantom subversives, soldiers under General John J. Pershing prepared to fight a more substantial foe. Somerset County, Pennsylvania offered hundreds of its sons to the cause, most of which found their way into Company C of the 110th Infantry, 28th Infantry ("Keystone") Division. Within a year of their enlistment, Somersetians found themselves on the front line of the war's most desperate fighting.

Formerly the 10th Pennsylvania National Guard, the 110th dated back to 1873. It was more experienced in quelling labor unrest, like the bloody Homestead Steel Strike of 1891, than combating enemies. Elements were mobilized for the Spanish-American War, but failed to see combat; more recently, the 10th was deployed along the Mexican border during John Pershing's failed expedition to capture Pancho Villa. On July 15th, 1917 Company C was formally mobilized in Somerset.

Its 140 enlistees reflected the makeup of its county: farmers, miners, merchants. Lawrence D. Hartle from Meyersdale, just twenty years old, had already spent three years working in a coal mine when war came. Alvy Martz, 28, worked a small farm near Glencoe; Walter Jones, was an electrical worker. Company command went to W. Curtis Truxal, an attorney from Meyersdale. They mobilized among much fanfare, receiving a parade and band celebration as they marched through Somerset. Later they were consolidated with Company C, 3rd Pennsylvania National Guard, swelling their ranks to 210 men.

Initially, Company C was billeted with the 25th Northumberland Fusiliers near Blequin. At this location they saw their first action, coming under aerial bombardment from German planes. The British unit trained the Americans in use of machine guns and gas masks, both necessities on the Western Front. Then in June they were reassigned to the French sector near Conde-en-Brie and retrained, rearmed and prepared for combat.

American soldiers like Lawrence Hartle found the experience disconcerting, as not only their postings and allies but their weapons changed frequently. "I had a Springfield rifle...but the man before me didn't take care of it and it kicked like a mule," Hartle would recall. "Then I had an American [sic] Lewis rifle [a British light machine gun]...then when we were attached to the British, they gave me a British Enfield rifle. Then the French gave me a [Lebel] rifle, which wasn't too good." Finally, by the time, they reached the front lines, they regained their Springfields.

On July 15th, 1918, just after midnight, German artillery began shelling the American positions. The Pennsylvanians, who were sitting down to a late supper, didn't appreciate the rude interruption and took cover in a position along the riverbank. Corporal Samuel Landis, serving the company's automatic rifle squad, was among the first casualties when a shell burst injured his leg. Despite his wounds, he refused to leave his men; later, he stated a simple motivation: "I couldn't leave the boys."

At around 3:30 am, the first Germans attempted to cross the Marne using pontoon boats. The American platoon nearest the shore, commanded by Lt. Robert J. Bonner, raked the Germans with machine guns and grenades, sinking the boats and strafing their passengers. Within minutes there were hundreds of German dead on the opposite shore or else floating in the river. Unfortunately, French troops to the Americans' left buckled under assault, and Company C found themselves surrounded. The first inkling of impending disaster came when the reserve platoon, commanded by Lt. Robert A. Floto, captured a German straggler at Conrthiezy, several miles to the American rear. Before Floto's men could process the implication, the vanguard of a German assault force crept within rifle range of the Americans. "All of the sudden," Private William Sarver recalled, "a voice from our rear called out in a cheerful and drawn-out A-ha! We looked around and saw thirty or more Germans."

The first inkling of impending disaster came when the reserve platoon, commanded by Lt. Robert A. Floto, captured a German straggler at Conrthiezy, several miles to the American rear. Before Floto's men could process the implication, the vanguard of a German assault force crept within rifle range of the Americans. "All of the sudden," Private William Sarver recalled, "a voice from our rear called out in a cheerful and drawn-out A-ha! We looked around and saw thirty or more Germans."

The Germans soon attacked, firing their weapons at near-point blank range into the American lines. Sarver was wounded four times in the action, while his friend Private Gilbert Blades was fatally injured. Despite ferocious resistance, Floto's men were overwhelmed, and the Germans tore into the next two platoons. The first platoon suffered a grievous loss when its commander, Lt. Samuel S. Crouse, was killed in the initial exchange of gunfire, and folded after close-range, hand-to-hand fighting.

Crouse's platoon and another commanded by Lt. Wilbur Schell fought their way towards the rear. Things went well until they crossed into a wheat field, where German machine guns sprung an ambush. Lt. Schell was wounded early in the fighting, along with Corporal Samuel Landis, already injured in the initial artillery barrage. There were moments of heroism amidst the chaos; Alvy Martz dropped seventeen Germans using a Colt pistol, while Walter Jones led a band of about eighteen doughboys through a gauntlet of fire. Jones won a Croix de Geurre and a Distinguished Service Cross for his heroism.

For many, the battle was just the first round. Samuel Landis waited for several days behind enemy lines, refusing to abandon his colleague Earl Wirick despite the latter losing his legs. The two made it to Allied lines, but Wirick died soon afterwards. William Sarver hid himself in a wheelbarrow and wheeled himself back to friendly territory. Reuben Rakeshaw made an arduous trek down the Marne: "I swam, waded and crawled down a creek for a mile and was in the water about eighteen hours."

Alvy Martz, already marked for gallant conduct, led seven men to join Walter Jones' group and the remnants of Lt. Floto's platoon. Spotting a column of prisoners being transported to the rear, Martz remarked laconically, "Guess we'd better see what we can do for those fellows." Along with John Mullen, a colleague from a Philadelphia company, Martz killed the German guards and freed their comrades. Martz earned a promotion to Sergeant and a Distinguished Service Cross

Company C's survivors found themselves in prison camps throughout Germany, with varying experiences. Lawrence Hartle found his Saxon guards friendly enough (though Prussians were mean), but thought the food disgusting and suffered from his injuries as "the Germans didn't even have aspirin" and his leggings "healed and broken open repeatedly." Captain Truxal was even less charitable, saying later that "I certainly will never have a very kindly feeling for the Germans" and labeling them "hogs."

Eventually, the men of Company C went back to their respective communities, the war becoming an experience to forget. While many harbored bitter feelings about the war ("The only thing I got out of the damn war," Hartle commented, "was two bad legs and a Purple Heart"), they could take pride in gallant service to their country in a desperate battle. No wonder General Pershing labeled them, along with others serving in the 28th Division, as "men of iron." Source Notes:

Source Notes:

This article owes a great debt to Charles Fox's "Company C and the Great War," a four-part series of articles which ran in the Laurel Messenger through 2004 and 2005. I have only found the final part online here. Other research draws upon the archives at the Somerset County Historical and Genealogical Center, particularly a private collection donated by Lawrence D. Hartle's grandson. An interview with Mr. Hartle, who died in 1998, can be viewed on YouTube.

Three books found online helped flesh out some of the 110th Regiment's historical background (and provided many of the images): John V. Hanlon's A History of Pittsburgh and Western PA Troops in the War (1919); H.G. Proctor's The Iron Division (1919) and History of the 110th Infantry (10th Pa.) of the 28th Division, U.S.A., 1917-1919 (1920).

Other articles on World War I and the Age of Wilson:

Formerly the 10th Pennsylvania National Guard, the 110th dated back to 1873. It was more experienced in quelling labor unrest, like the bloody Homestead Steel Strike of 1891, than combating enemies. Elements were mobilized for the Spanish-American War, but failed to see combat; more recently, the 10th was deployed along the Mexican border during John Pershing's failed expedition to capture Pancho Villa. On July 15th, 1917 Company C was formally mobilized in Somerset.

Its 140 enlistees reflected the makeup of its county: farmers, miners, merchants. Lawrence D. Hartle from Meyersdale, just twenty years old, had already spent three years working in a coal mine when war came. Alvy Martz, 28, worked a small farm near Glencoe; Walter Jones, was an electrical worker. Company command went to W. Curtis Truxal, an attorney from Meyersdale. They mobilized among much fanfare, receiving a parade and band celebration as they marched through Somerset. Later they were consolidated with Company C, 3rd Pennsylvania National Guard, swelling their ranks to 210 men.

Keystone Division arrives in France (source)

After training at Camp Hancock near Augusta, Georgia, they embarked for Dover, England in April 1918. From there, they soon reached France, arriving just as General Erich Ludendorff launched his Spring Offensive, a desperate, last-ditch effort by Germany to crush the Allies before American troops could arrive in sufficient numbers to balance them out. Thus their deployment became a matter of urgency, with their British and French allies working double-time to crack the doughboys into shape.Initially, Company C was billeted with the 25th Northumberland Fusiliers near Blequin. At this location they saw their first action, coming under aerial bombardment from German planes. The British unit trained the Americans in use of machine guns and gas masks, both necessities on the Western Front. Then in June they were reassigned to the French sector near Conde-en-Brie and retrained, rearmed and prepared for combat.

American soldiers like Lawrence Hartle found the experience disconcerting, as not only their postings and allies but their weapons changed frequently. "I had a Springfield rifle...but the man before me didn't take care of it and it kicked like a mule," Hartle would recall. "Then I had an American [sic] Lewis rifle [a British light machine gun]...then when we were attached to the British, they gave me a British Enfield rifle. Then the French gave me a [Lebel] rifle, which wasn't too good." Finally, by the time, they reached the front lines, they regained their Springfields.

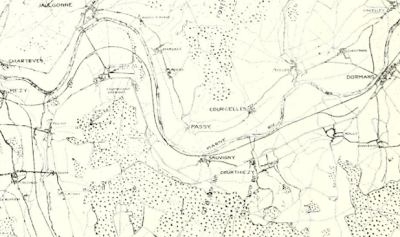

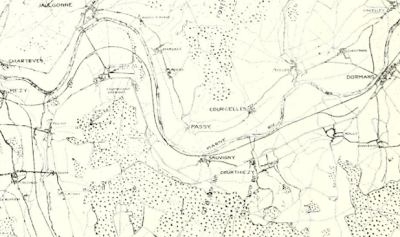

Map of Company C's position (source)

Finally in July, Company C found itself posted near Savigny, along the Marne River. They were flanked by the 113th French infantry regiment and other units from the American 110th. One platoon overlooked the river on a hill, with two deployed slightly to the rear along a railroad; the fourth, a mile back in reserve. This put them square in the cross hairs of the next German offensive, with . One melodramatic historian commented that "the gates to glory and to death swung wide for many a Pennsylvania lad that night."On July 15th, 1918, just after midnight, German artillery began shelling the American positions. The Pennsylvanians, who were sitting down to a late supper, didn't appreciate the rude interruption and took cover in a position along the riverbank. Corporal Samuel Landis, serving the company's automatic rifle squad, was among the first casualties when a shell burst injured his leg. Despite his wounds, he refused to leave his men; later, he stated a simple motivation: "I couldn't leave the boys."

At around 3:30 am, the first Germans attempted to cross the Marne using pontoon boats. The American platoon nearest the shore, commanded by Lt. Robert J. Bonner, raked the Germans with machine guns and grenades, sinking the boats and strafing their passengers. Within minutes there were hundreds of German dead on the opposite shore or else floating in the river. Unfortunately, French troops to the Americans' left buckled under assault, and Company C found themselves surrounded.

The Germans soon attacked, firing their weapons at near-point blank range into the American lines. Sarver was wounded four times in the action, while his friend Private Gilbert Blades was fatally injured. Despite ferocious resistance, Floto's men were overwhelmed, and the Germans tore into the next two platoons. The first platoon suffered a grievous loss when its commander, Lt. Samuel S. Crouse, was killed in the initial exchange of gunfire, and folded after close-range, hand-to-hand fighting.

Crouse's platoon and another commanded by Lt. Wilbur Schell fought their way towards the rear. Things went well until they crossed into a wheat field, where German machine guns sprung an ambush. Lt. Schell was wounded early in the fighting, along with Corporal Samuel Landis, already injured in the initial artillery barrage. There were moments of heroism amidst the chaos; Alvy Martz dropped seventeen Germans using a Colt pistol, while Walter Jones led a band of about eighteen doughboys through a gauntlet of fire. Jones won a Croix de Geurre and a Distinguished Service Cross for his heroism.

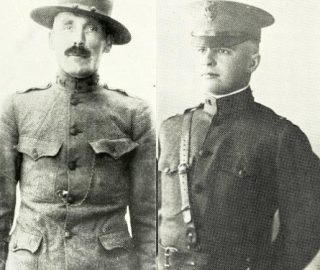

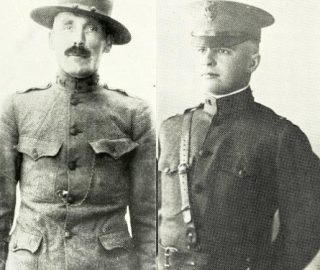

Lts. Samuel Crouse (left) and Wilbur Schell (source)

After Schell's platoon collapsed, only Lt. Bonner's men remained. Pinned against the Marne, they fought desperately against overwhelming odds. Lawrence Hartle and Herbert P. Jones faced the brunt of the German onslaught, surviving shellfire, machine guns and even flamethrowers. Hartle and Jones killed a slew of Germans until they were wounded and beaten unconscious by their attackers. Despite such resistance, all of Bonner's platoon were taken prisoner. Captain Truxal, who had been separated from his company, fell in with a small band of French troops who was soon forced to surrender.For many, the battle was just the first round. Samuel Landis waited for several days behind enemy lines, refusing to abandon his colleague Earl Wirick despite the latter losing his legs. The two made it to Allied lines, but Wirick died soon afterwards. William Sarver hid himself in a wheelbarrow and wheeled himself back to friendly territory. Reuben Rakeshaw made an arduous trek down the Marne: "I swam, waded and crawled down a creek for a mile and was in the water about eighteen hours."

Alvy Martz, already marked for gallant conduct, led seven men to join Walter Jones' group and the remnants of Lt. Floto's platoon. Spotting a column of prisoners being transported to the rear, Martz remarked laconically, "Guess we'd better see what we can do for those fellows." Along with John Mullen, a colleague from a Philadelphia company, Martz killed the German guards and freed their comrades. Martz earned a promotion to Sergeant and a Distinguished Service Cross

Alvy Martz (source)

Such heroism put the best face possible on a calamity. Of Company C's 210-man complement, only 36 escaped capture; 43 were killed and 68 wounded. Though he hadn't been able to join his men, Captain Truax took comfort in seeing "piled up on the river bank hundreds of Germans killed by our automatic rifles." The Germans had driven a wedge nine miles long into the American lines, but American, British and French reinforcements soon plugged their advance and counterattacked, ending Ludendorff's last offensive.Company C's survivors found themselves in prison camps throughout Germany, with varying experiences. Lawrence Hartle found his Saxon guards friendly enough (though Prussians were mean), but thought the food disgusting and suffered from his injuries as "the Germans didn't even have aspirin" and his leggings "healed and broken open repeatedly." Captain Truxal was even less charitable, saying later that "I certainly will never have a very kindly feeling for the Germans" and labeling them "hogs."

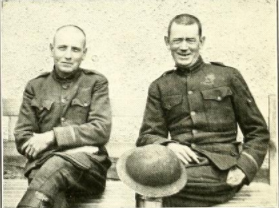

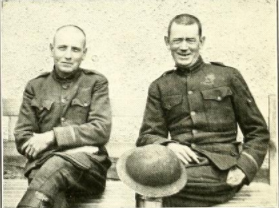

Captain Truxal (left) with another officer in captivity (source)

News of Company C's exploits slowly trickled back home, pride mixing with shock and trepidation. The War Department gave contradictory reports about the fates of missing soldiers, forcing Congressman Thomas S. Crago to launch an inquiry. Eventually, the Red Cross contacted the surviving men, sending them food parcels and exchanging letters from home. The Americans didn't return to Somerset until May 24th, 1919, whereupon they received a hero's welcome.Eventually, the men of Company C went back to their respective communities, the war becoming an experience to forget. While many harbored bitter feelings about the war ("The only thing I got out of the damn war," Hartle commented, "was two bad legs and a Purple Heart"), they could take pride in gallant service to their country in a desperate battle. No wonder General Pershing labeled them, along with others serving in the 28th Division, as "men of iron."

This article owes a great debt to Charles Fox's "Company C and the Great War," a four-part series of articles which ran in the Laurel Messenger through 2004 and 2005. I have only found the final part online here. Other research draws upon the archives at the Somerset County Historical and Genealogical Center, particularly a private collection donated by Lawrence D. Hartle's grandson. An interview with Mr. Hartle, who died in 1998, can be viewed on YouTube.

Three books found online helped flesh out some of the 110th Regiment's historical background (and provided many of the images): John V. Hanlon's A History of Pittsburgh and Western PA Troops in the War (1919); H.G. Proctor's The Iron Division (1919) and History of the 110th Infantry (10th Pa.) of the 28th Division, U.S.A., 1917-1919 (1920).

Other articles on World War I and the Age of Wilson:

- The American Protective League and the War on Slackers, 1917-1919

- The Eastern Front, 1914-1917 (1975, Norman Stone)

- The Guns of August (1962, Barbara W. Tuchman)

- The Hun's Shadow in America, 1917-1918

- Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I (2014, Alexander Watson)

- The Siege (1970, Russell Braddon)