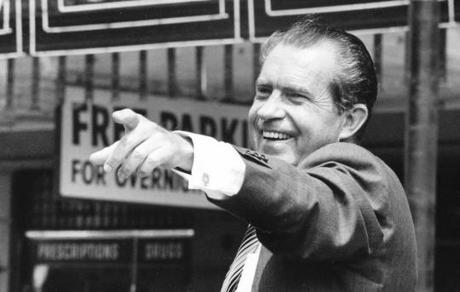

Prior to July 16th, 1973, the Watergate scandal remained containable. Despite the revelations of the Washington Post, the high drama of Sam Ervin's televised Senate hearings, John Dean's incriminating testimony, there was still no direct evidence of Richard Nixon's wrongdoing - nor did there seem likely to be. Just a lot of smoke, mirrors and contradictory counterclaims, which could be chalked up to partisan grandstanding.

Prior to July 16th, 1973, the Watergate scandal remained containable. Despite the revelations of the Washington Post, the high drama of Sam Ervin's televised Senate hearings, John Dean's incriminating testimony, there was still no direct evidence of Richard Nixon's wrongdoing - nor did there seem likely to be. Just a lot of smoke, mirrors and contradictory counterclaims, which could be chalked up to partisan grandstanding.Then Alexander Butterfield, an aide to former White House chief of staff H.R. Haldeman, dropped the biggest bombshell to date. He revealed to the Senate that President Nixon tape-recorded conversations in the Oval Office, something previously known to only a handful of people. Suddenly, everyone realized that Howard Baker's unanswerable question - "What did the President know, and when did he know it?" - might, in fact, be answerable.

Yet Nixon stonewalled, insisting that releasing the tapes "would risk exposing private Presidential conversations" and compromise the White House. Requests from Senator Ervin for access fell on deaf ears; a formal subpoena met with pleas of executive privilege. Yet Nixon ignored the pleas of aides to destroy the tapes, making them a tantalizing yet unattainable prize. If only investigators could get hold of them.

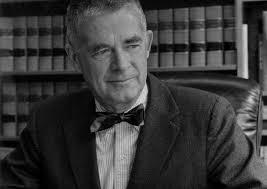

Archibald Cox

That unenviable task fell to Archibald Cox, the Watergate Special Prosecutor. Bow-tied and gray-haired, former Solicitor General and occasional Harvard Professor, semi-retired and partially deaf, Cox seemed perfect for a nonpartisan investigation. In fact, as Rick Perlstein writes, he represented "everything Richard Nixon hated," and he found the President little interested in cooperating. As early as April, in fact, Cox had learned of the taping system and requested relevant excerpts. Nixon's attorney, Fred Buzhardt, flatly refused, setting the tone for their relationship.After Nixon declined a subpoena from Cox, Judge John Sirica issued a summons for the President to defend his actions. On August 22nd, Cox and presidential counsel Charles Alan Wright clashed in Sirica's courtroom. When Wright again pleaded executive privilege, Cox insisted, "Not even a President can be allowed to select some accounts of a conversation for public disclosure and then to frustrate further grand jury inquiries by withholding the best evidence of what actually took place."

Cox then demanded Nixon either comply with subpoena or "dismiss the case," adding that if he follows the latter course, "the people will know where the responsibility lies." Wright responded with a veiled threat, commenting that "Whether a decision adverse to the President could be enforced is a question." Judge Sirica issued his decision on August 29th, requesting that Nixon turn the tapes over to him. The President suggested he'd appeal Sirica to the Supreme Court while adding that he might look for ways to "otherwise sustain" his position.

Cox and Elliot Richardson

Meanwhile, Attorney General Elliot Richardson waffled between supporting the President and defending Cox, asserting executive privilege while insisting that the Special Prosecutor was acting "in full accord with the requirements of his job." But Richardson also felt increased White House pressure to rein in Cox, or else focus on his investigation into Vice President Spiro Agnew's improprieties instead. Richardson concluded that "Richard Nixon was more likely to be guilty than stupid."That fall, Americans were temporarily distracted by Augusto Pinochet's coup in Chile, a new Middle East war between Egypt and Israel and a resultant spike in oil prices. Agnew resigned on October 10th, admitting guilt for tax fraud in return for a suspended sentence; Gerald Ford soon replaced him. The Los Angeles Times, once a staunch Nixon supporter, sarcastically advised young Americans to go into public service so they'd have "the privilege of committing felonies." Increasingly, it seemed like America housed no bigger felon than its President.

On October 12th, the Court of Appeals upheld Sirica's ruling, demanding that Nixon divulge the tapes to Judge Sirica. "Though the President is elected by nationwide ballot...he does not embody the nation's sovereignty," the court intoned: "He is not above the law's commands." Nixon, distracted by arranging emergency military aid to Israel, delegated the matter to his attorneys and to Alexander Haig, who confronted Richardson with a devious game plan.

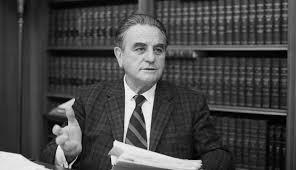

John Sirica, Nixon nemesis

After discussing the Yom Kippur War, Haig told that Richardson could play a major role in resolving the ongoing crisis. "I'll go home and pack my bags," the Attorney General responded, thinking he meant Israel. Haig responded, "That's not exactly what I have in mind," instead laying out Nixon's plan to fire Cox, who after all was merely "a creature of the President." Richardson indignantly refused, saying that he could only fire Cox "for extraordinary improprieties" and threatening to resign. For now, Haig backed down.Later that day, Haig called Richardson with a new proposal: they would hand the tapes to Senator John Stennis, a Mississippi Democrat, as a third party to provide transcripts. Richardson ran the proposal by Cox, who on October 16th responded with a detailed list of objections. Americans should not confide the investigation to "one man operating in secrecy, consulting only with the White House." Nixon grew increasingly impatient, telling Richardson that with Agnew out of the way, "we can go ahead and get rid of Cox."

There was one last, bungled effort at compromise. On Friday, October 19th, Nixon met with Sam Ervin and Howard Baker, hoping to woo them to his "Stennis compromise." The Senators agreed to consider this offer, leading the White House to prematurely announce their approval. Disgusted, Ervin immediately repudiated the President's statement, and the confrontation lurched forward. Cox assembled his staff and issued a defiant statement, commenting that "I cannot be a party to such an agreement." When a reported asked if he would resign, Cox barked "Hell, no!"

John Stennis

Saturday, October 20th. At 1:00 pm, Cox gave an hour-long press conference explaining his position. "I'm not out to get the President of the United States," he insisted, before laying out his reasons for resisting the Stennis compromise: namely, the President circumvented accepted procedures and institutions for an ad hoc investigation. Cox disclosed a conversation with Charles Alan Wright, where he'd told the attorney that "things...were drawn in such a way that I could not accept them."Afterwards, Leonard Garment, the Chief White House counsel, politely asked Richardson to fire Cox: the Attorney Richardson refused. Al Haig called Richardson a few minutes later, ordering him to do so. "I can't do that," Richardson said, offering his resignation. He waited tensely for a summons with his deputy William Ruckelshaus, who affirmed solidarity with Richardson, and Solicitor General Robert Bork, who supported firing Cox.

At around 3:30, Richardson arrived at the Oval Office, finding Nixon, frazzled from managing the Middle East crisis, and Haig, coolly angry, waiting for him. The President begged with Richardson to postpone his resignation, saying that doing so amidst the war in Israel would make him look weak. When Richardson demurred, Nixon suggested that he fire Cox, then resign to satisfy both of them.

"Mr. President," Richardson insisted, "I feel I have no choice but to go forward with this."

Alexander Haig

"Be it on your head," Nixon said petulantly. "I am sorry that you feel you have to act on the basis of a purely personal commitment rather than the national interest."Infuriated, Richardson responded: "I'm acting on the basis of national interest as I see it." The President terminated the conversation by muttering, "Your perception of national interest is so different than mine." Then Richardson bade the President farewell and exited; arriving back at his office, he muttered "The deed is done."

At 5:15, Haig called William Ruckelshaus. Again, he emphasized the international crisis as cause for compliance, adding that the President was "depending on" the Deputy to follow orders. Ruckelshaus suggested waiting a weak, then found Haig reverting to his peremptory default: "Your commander in chief has given you an order. You have no alternative." "Other than to resign," Ruckelshaus replied. And so he did.

William Ruckelshaus

Now came Robert Bork's turn. In a strangely comic scene, Fred Buzhardt and Len Garment drove to the Justice Department incognito, smuggling the Solicitor General to the White House in a black limousine. "They looked like a couple of mafiosi," Bork commented later. He arrived at the White House, where Haig presented him with a two-paragraph letter ordering him to "discharge Mr. Cox immediately." Bork briefly hesitated, then signed it and sent it by messenger to Cox.Upon receiving Bork's letter, Cox called a reporter and issued a statement for the ages: "Whether we shall continue to be a Government of laws and not of men is now for Congress and ultimately the American people to decide." He received a phone call from Elliot Richardson, who explained that he too had resigned and attempted to succor his friend with words from Homer's Illiad: "Let us go forward together, and either we shall give honor to one another, or another to us."

Across town, White House press secretary Ron Ziegler curtly announced the resignations, and Cox's dismissal, at 8:25. Then he dropped another bombshell: "The office of the Watergate special prosecution force has been abolished as of approximately eight p.m. tonight." Accordingly, FBI agents descended upon Cox's office, sealing the office's files and dismissing the prosecutor's staff. Others closed off Richardson and Ruckelshaus's offices.

Robert Bork

Outside Cox's office, Justice Department aide Henry Ruth tearfully read a statement to the press. "One thinks in a democracy this would not happen," comparing events to the novel Seven Days in May. He'd been humiliated when armed FBI agents prevented him from removing personal affects from his desk. Jim Doyle, another aide, was also stopped while trying to remove a document. "It's the Declaration of Independence," he snapped to the agent. "Just stamp it void and let me take it home."Indeed, the immediate reaction was that Nixon executed something like a coup d'etat. Ted Kennedy warned of America becoming "Chile without the bloodshed"; Robert Byrd denounced the "Saturday Night Massacre" as "a Brown Shirt operation." Senator Robert Packwood, a Republican, thundered that "The office of the President does not carry with a license to destroy justice in America." Speaker of the House Carl Albert proclaimed himself "past the point of reacting." Impeachment resolutions soon found their way into the House of Representatives, setting Nixon's downfall in motion.

The press followed suit. NBC proclaimed it "the most serious constitutional crisis in its history." Time magazine called for impeachment. Fred Emery of the London Times wrote that "there was a whiff of the Gestapo in the chill October air." Another reporter commented that "I'm going to go home and read about the Reichstag fire." Usually, likening the President of the United States to Adolf Hitler was the province of kooks and radicals. Now Congress and the mainstream media openly did so.

After Saturday's dramatic events, Judge Sirica's court summons on October 23rd - demanding compliance with his previous orders to turn over the tapes - was fraught with tension. Charles Alan Wright strode into the courtroom, his attitude reminding J. Anthony Lukas of Gary Cooper in High Noon, faced by eleven of Cox's glowering staff members. Sirica asked Wright whether he was ready to comply with his previous order, fully expecting to cite the attorney - and the President - with contempt.

"I am not prepared at this time to file a response," Wright commented. Then he changed tracks, saying that "the President of the United States would comply in all respects with the order of August 29th as modified by the Court of Appeals." He then added, seeking to reassure Judge Sirica (and the nation) that "This President does not defy the law."

Nixon, after initial defiance, had backed down. He turned over the tapes, setting in motion the next round of recriminations, culminating in the release of transcripts that ultimately doomed his presidency. He appointed another special prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, who proved no more pliable than Cox. And he proved, unwittingly, that no President, however devious, high-handed or amoral, could not be held accountable but for his misdeeds.

This article draws upon: Fred Emery, Watergate: The Corruption of American Politics and the Fall of Richard Nixon (1994); Stanley Kutler, The Wars of Watergate: Richard Nixon's Final Crisis (1992); J. Anthony Lukas, Nightmare: The Underside of the Nixon Years (1976); Rick Perlstein, The Invisible Ridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan (2014); and Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, The Final Days (1976).

Special thanks as well to our current President, for demonstrating that history repeats itself more often than we'd like to think.

Other articles on Richard Nixon:

- Richard Nixon's Deplorables

- The Sad, Sorry World of Watergate Memoirs

- Spiro Agnew Grooves On

- The State Department and the Madman, 1969-1970