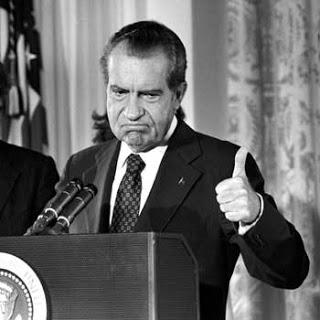

From the start, Watergate married tragedy to farce. There was the "third-rate burglary" itself, botched by a team of inane adventurers too dumb to cover their tracks. There was the high drama of the Senate's Ervin Committee, offering scintillating testimony and shocking revelations fit for a soap opera. Then the awkward tragicomedy of the Saturday Night Massacre, the vulgar disclosures of the White House tapes, Richard Nixon's increasingly implausible denials, Spiro Agnew's tax scandal.

From the start, Watergate married tragedy to farce. There was the "third-rate burglary" itself, botched by a team of inane adventurers too dumb to cover their tracks. There was the high drama of the Senate's Ervin Committee, offering scintillating testimony and shocking revelations fit for a soap opera. Then the awkward tragicomedy of the Saturday Night Massacre, the vulgar disclosures of the White House tapes, Richard Nixon's increasingly implausible denials, Spiro Agnew's tax scandal. Then there were Nixon's die-hard supporters. He won reelection with an astonishing 60.7 percent in 1972, the fruit of his dirty tricks and George McGovern's ineffectual campaign. Now, as Watergate consumed his presidency, Nixon's approval rating hovered in the low-to-mid 20s. All that remained were a stubborn residue of his Silent Majority, joined with flaks, flunkies and oddballs to defend the indefensible.

Nixon and George Wallace in Huntsville, Alabama

Nixon's electoral strategy crafted a "New Majority" blending Republicans with disaffected Democrats: Southerners resenting Civil Rights, Northern ethnics, organized labor and shell-shocked suburbanites. Nixon's rhetoric of "positive polarization" blamed America's ills on liberal Democrats, academics, the media, angry blacks and unruly protestors. Indignant Americans embraced Nixon's angry rhetoric and easy explanations, countenancing all Presidential actions as necessary.Throughout early 1974, with impeachment looming and his lawyers stonewalling Congress, Nixon barnstormed the South. In February he met George Wallace, segregationist icon and Nixon's electoral rival, in Huntsville, Alabama. Once, Nixon had the IRS audit Wallace's brother Gerald and fed campaign money to his 1970 opponent, Albert Brewer; until an assassin crippled Wallace in 1972, he feared the Governor more than his liberal opponents. Now, all seemed forgiven.

"I submit that you are among friends!" Wallace assured Nixon before an enthusiastic Alabamian crowd, who oddly waved signs favorably comparing Nixon to Abraham Lincoln. Odder still was Wallace's insistence that "We in Alabama have always honored the office of the Presidency of the United States," forgetting his schoolhouse defiance of John F. Kennedy, confrontations with Lyndon Johnson and attacks on Nixon over school busing.

Nixon and Roy Acuff at the Grand Ole Opry

A month later, Nixon journeyed to Nashville, Tennessee for the opening of the new Grand Ole Opry. Thousands of cheering Southerners greeted Nixon, including a coterie of country music stars: Johnny Cash, Roy Acuff and Minnie Pearl among them. Nixon remarked that "Country music radiates a love of this nation...Country music is America," then played piano for his wife Pat, with backing from the Opry orchestra. Stealing Acuff's signature trick, he awkwardly dangled a yoyo that refused to bounce.Northern conservatives also defended Nixon as a bulwark against amorality. "Watergate is bullshit!" shouted an Italian-American from Brooklyn's Canarsie neighborhood. "I don't care what he did. It's disgraceful what they did to the country - the press and Congress and the protestors!" A Richmond Hills Republican neatly summarized conservative fears, commenting that liberals were "encouraging poor Negros to come up here and endorsing fornication and supporting illegitimate children."

Even the hard right, largely distrustful of Nixon, rallied around the President. William Loeb of the Manchester Union Leader, who'd endorsed far-right Democrat Sam Yorty in 1972, dropped his attacks on Nixon to call Watergate a left wing coup. M. Stanton Evans, writer and cofounder of Young Americans for Freedom, quipped that "I never liked Nixon until Watergate." William F. Buckley observed that such conservatives supported Nixon "because the alternative was to wake up and find that they are in agreement with...the New York Times."

Nixon encouraged these responses, claiming "If I were a liberal, Watergate would be a blip." Ron Ziegler, White House press secretary, called Congress a "kangaroo court." Pat Buchanan, sometimes Nixon speechwriter, editorialized that "the President's tradition adversaries were happily drawing up surrender terms." Another aide, Kenneth Clawson, referred to the investigations as "an attempted coup d'état of the US government."

Ron Ziegler

Even Nixon's release of the White House tapes in April 1974 didn't daunt his hardcore supporters. Ronald Reagan insisted that "I don't think anyone can make any judgment until they have read the entire 1,2000 pages" of transcript. John McLaughlin, former Jesuit priest and future TV host, called Nixon the "greatest moral leader of the last third of this century" and defended Nixon's Jew-baiting rants as "good, valid...therapy." And Chuck Colson, ex-White House Counsel, dismissed the President's foul mouth as "typical locker room talk."When rhetoric failed, the President's men acted. As the House Judiciary Committee began impeachment proceedings, they received scripted phone calls denouncing "the lynch mob atmosphere created in [Washington] by the Washington Post and other parts of the Nixon-hating media." These were the brainchild of Karl Rove, then a College Republican organizer, who created "Americans for the Presidency" as a propaganda front.

This Astroturf campaign coincided with grassroots action. Twenty thousand supporters cheered a Nixon rally in Macon, Georgia. Various musicians crafted pro-Nixon ballads, including Fred Boyd's "Stand Up and Cheer for Richard Nixon," borrowing the tune for "Okie from Muskogee." Supporters sported "Get Off the President's Back" buttons and "Nobody Died at Watergate" bumper stickers (a slam at Ted Kennedy). Young Americans for Freedom organized the Citizens Opposed to Impeachment, sending mailings and organizing rallies for young Nixon backers.

So Korff purchased a New York Times ad in July 1973, entitled "An Appeal for Fairness." It was an angry, semi-coherent diatribe attacking the Senate hearings as "a perfect amalgam of circus performance and popularity contest" and comparing Watergate to the French Revolution. Within days, Korff's missive generated 3,000 letters, hundreds of phone calls and $30,000 in donations.

Korff created the National Citizens' Committee for Fairness to the Presidency. Claiming 2.5 million members, Korff became a minor celebrity, appearing on The Dick Cavett Show, hosting rallies across the country and publishing luridly-titled editorials ("The Rape of America"). Korff's language bordered on hysteria, positing Nixon as a victim whose "blood has been sapped by vampires."

Nixon's Rabbi: Baruch Korff meets the President

The Committee became one of Nixon's most persistent champions. Korff's rallies attracted thousands, who praised Nixon while threatening reporters and hecklers. His followers swarmed the Capitol, pigeonholing Republican Tom Railsback not to indict the President on circumstantial evidence. Another pursued Barbara Jordan, Texas Democrat, through the halls shouting "I'm for the President!" "A lot of people are!" Jordan snapped.Nixon embraced his unlikely champion. A brief meeting in December 1973 snowballed to regular contacts, including a 90 minute interview in May 1974 (later published as a book, The Personal Nixon). At a rally in July, an embattled President praised Korff's "eloquence, his intelligence, his dedication" as "a great source of strength to me." Korff defended Nixon to the last, imploring him as late as August 6th not to resign.

However eccentric, Korff's affection for Nixon was sincere. Reverend Sun Myung Moon, head of the Unificaton Church, wasn't so idealistic. The Korean cult leader viewed Watergate as an opportunity to boost his profile, ingratiate himself with the Republican Party... and to posit himself as the spiritual leader prepared to heal a divided America. "If this dying person, Nixon, is revived," Moon mused, "then Reverend Moon's name will be more popular and famous."

The President and the Messiah: Nixon meets Reverend Moon

Through his Freedom Leadership Foundation, Moon published ads, gave speeches and organized demonstrations across the world, from the United States to Seoul and even Tokyo, where 25,000 Moonies carted a giant papier-mâché Nixon through the streets. Moon sent buses full of supporters to New York and Washington, wearing placards urging onlookers to "Forgive, Love and Unite" or announcing their prayers for a Congressman's soul."God has chosen Nixon through the will of the people," said Moon, who viewed a celestial theocracy preferable to democracy. "It is the people's duty to support him." His followers treated Nixon himself as a deity, referring to him as an "archangel" and kneeling during Nixon's public appearances. A bemused Garry Wills wrote "When a man has sacrificed all honor, he must settle for adoration."

After a lengthy correspondence, President and Messiah finally met in February 1974, an awkward meeting where Moon urged Nixon to fast for his sins and led him in a Korean-language prayer. Unlike Korff, Nixon afterwards kept Moon at arm's length, but his supporters organized fasts and prayer vigils over the coming months. Moon leveraged his actions into an American business empire, including the Washington Times newspaper, until his indictment for tax fraud in 1982.

Moonies for Nixon: New York, August 1974

Men less exalted than Moon or Korff entertained less celestial concerns. Republican politicians considered Nixon an insoluble problem: their party's leader, but a liability for the 1974 elections. Brave men like Massachusetts Senator Edward Brooke and Illinois Congressman John Anderson urged resignation or impeachment. Others, like Senate Minority Leader Hugh Scott, criticized Nixon's words and actions but retained nominal support. Still others opted for full-bore support.As the House Judiciary Committee held impeachment hearings in July 1974, eleven Republicans remained on Nixon's side. Charles Sandman of New Jersey, compared to Joe McCarthy, snarled that "the President is entitled to know exactly what he's done wrong." Charlie Wiggins of California made a similar argument, attacking the lack of specificity in impeachment charges. This led an exacerbated William Cohen, Republican from Maine, to exclaim that there was no smoking gun: "The whole room is full of smoke!"

It seems odd that these Congressmen lashed themselves to a sinking ship. While some entertained personal loyalty, others weighed political considerations; after all, most Nixon die hards were rock-ribbed Republicans. John Rhodes, House Minority Leader, noted that his tentative comments about resignation brought an angry deluge of pro-Nixon letters. He told Elizabeth Drew that "Any Republican who thinks he can win a congressional election without that hardcore support is more optimistic than I am."

Denouement: Hugh Scott, Barry Goldwater and John Rhodes, August 7th, 1974

Finally, the ball dropped on August 5th. The "smoking gun" tape of June 23rd, 1972, showing Nixon directing the Watergate cover-up, removed any doubt of complicity. Rhodes, Scott and Barry Goldwater marched into the White House two days later, pushing Nixon to resign. Alexander Haig, his beleaguered chief of staff, and Nixon's lawyers already pushed him in that direction.These revelations didn't stop the Moonies from swarming the Capitol steps, nor did it stop Indiana Congressman Earl Landgrebe from appearing on NBC's Today Show on August 8th. Landgrebe resorted to violent stubbornness: "I'm sticking with my president even if he and I have to be carried out of this building and shot!" Nixon announced his resignation that evening, sparing Landgrebe from Jim Hartz's wrath.

These days, Richard Nixon sports more reasonable defenders: academics who weigh his achievements against his transgressions, conservatives who feel he was scapegoated for systemic malfeasance. In his darkest hour however, Tricky Dick could only take succor from friends, family, committed staffers and motley supporters no evidence or argument could shake.

Sources for this article include: Elizabeth Drew, Washington Journal: The Events of 1973-1974 (1975); John Gorenfeld, Bad Moon Rising: How Reverend Moon Created the Washington Times, Seduced the Religious Right and Built an American Kingdom (2008); David Greenberg, Nixon's Shadow: The History of an Image (2003); J. Anthony Lukas, Nightmare: The Underside of the Nixon Years (1975); Rick Perlstein, The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan (2014); Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, The Final Days (1976).

Special thanks to Rick Perlstein, both for offering research suggestions for this article, and for helping trigger my fascination with Tricky Dick and his times. Now you know who to blame.

Other Groggy articles on Richard Nixon and Presidential politics:

- Eugene McCarthy Versus the Democratic Party, 1968

- George Wallace Stands Up For America, 1968

- Nelson Rockefeller and the Demise of the Liberal Republican

- The Sad, Sorry World of Watergate Memoirs

- Spiro Agnew Grooves On

- William Scranton for President, 1964

- William Scranton for President, 1964: Part Two