The violence in Philadelphia inspired outrage rather than copycats. Besides the general disgust over Nativist extremism, other issues occupied America's attention. The Mexican War harnessed anti-Catholic sentiments to Manifest Destiny: Stephen F. Austin, cofounder of Texas, had denounced "Rome...that mother of executions, assassins, robbers and tyrants" and Sam Houston became a Know-Nothing leader. Thus imperialism became a quest to liberate the west from Catholic tyranny.

The violence in Philadelphia inspired outrage rather than copycats. Besides the general disgust over Nativist extremism, other issues occupied America's attention. The Mexican War harnessed anti-Catholic sentiments to Manifest Destiny: Stephen F. Austin, cofounder of Texas, had denounced "Rome...that mother of executions, assassins, robbers and tyrants" and Sam Houston became a Know-Nothing leader. Thus imperialism became a quest to liberate the west from Catholic tyranny. The war's main effect wasn't stoking Nativist passions but inflaming tension over slavery, with the long-dormant debate over the South's "peculiar institution" inflamed by an infusion of new territory. After several years of argument, Congress crafted the Compromise of 1850, which granted freedom to western territory in exchange for a strict Fugitive Slave Act. Tensions momentarily cooled, Americans could focus on the massive influx of immigrants.

Two events in 1848 led to an inundation of foreigners. First was the Irish Potato Famine, which induced millions of Irishmen to flee their homeland in response to mass starvation. Then came Europe's upheavals of 1848, continent-wide revolts against autocratic regimes in France, Germany, Italy and elsewhere. Their failure led to an influx of refugees, especially from the German states, of liberal and radical leaders to the United States.

Celtic Holocaust: Irish refugees fleeing the Potato Famine

Americans despised the Irish as a threat to American workers, bringing crime, pestilence and alien allegiances to the New World. Nativists savaged Irishmen as "the chief source of crime in this country" and bemoaned that "dire wretchedness, appalling want and festering famine have tended to change their characters." Their politics were also suspect: Alabama nativist S.F. Rice branded them "by nature abolitionist," while, conversely, Whigs detested their attachment to the Democratic Party.The German "Forty-Eighters" offered a different threat. Educated and politically progressive, Protestant or even atheist, they became active in America, joining the anti-slavery cause in western states like Missouri, Kentucky and Wisconsin. Carl Schurz and Franz Sigel were among the refugees who became prominent, as abolitionist editors and activists, as Union generals in the Civil War, as leaders of the Republican Party afterwards.

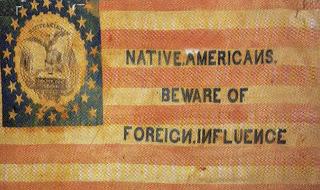

Immigrants, German or Irish, Catholic or not, thus became undesirable politically and morally. A Whig politician warned Charles Sumner, Massachusetts Senator and anti-slavery leader, that "this Catholic power is felt to be...a more dangerous power than the Slave Power and therefore absorbs all other considerations." For several years, much of the nation placed its sectional schism on hold to combat alien influences within its midst.

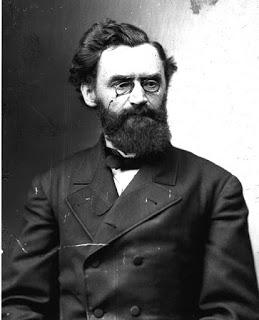

Carl Schurz, German rebel turned American Republican

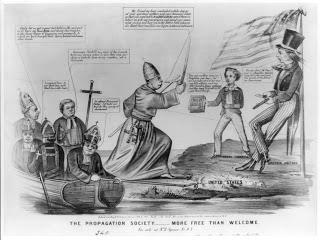

The Catholic Church, rather than immigrants or Know-Nothings (as they were becoming known), sparked the next outrage. Tone-deaf when not provocative in response to Nativist attacks, the Church committed a grave blunder in 1853. Pope Pius IX sent Cardinal Gaetano Bedini, recently the Archbishop of Thebes, to settle disputes over church property in New York, followed by a general tour of the United States. It was the first time a papal nuncio visited America, and Bedini proved a poor choice.Though experienced in resolving Church conflicts in Italy and Brazil, Bedini embodied reactionary Papism. As commissary extraordinary at Bologna during the 1848 unrest, he suppressed revolutionaries with savage violence, earning the nickname "the Butcher of Bologna." Bedini was also arrogant, limited in his English and ignoring American church leaders who asked that he limit his travels to friendly cities. On a mission from God, or at least Rome, Bedini saw no reason to observe tact.

From his initial arrival in New York in June 1853, Bedini attracted scorn. "He is here," railed the New York Observer, "to find the best way of riveting Italian chains upon us." In Boston, Nativists burned Bedini in effigy, denouncing him as a "cloven-hoofed enemy of freedom." Ignoring these insults, Bedini delivered a papal letter to President Franklin Pierce in Washington, then headed to Buffalo and Philadelphia to resolve disputes over church property. If he'd stopped there, Bedini's mission might have been a success.

Cardinal Bedini, Avatar of Catholic Arrogance

A savage provocateur stalked Bedini across the country. Alessandro Gavazzi, an Italian ex-priest who'd left the clergy after supporting the rebels of '48, arrived in America with a fiery message of his own. "Popery cannot be reformed!" he thundered, proclaiming "I am a Destroyer!" In Quebec and Montreal, angry Canadian Catholics rioted in response to his call for "nothing but annihilation!" Gavazzi found American audiences more receptive, answering his speeches with violence against Catholics.After spending time in New York, Bedini pressed on to western Pennsylvania in December 1853. After a friendly reception in Loretto, which caused Bedini to exclaim, "I have not seen such faith in Israel!" he moved on to Pittsburgh. The city was a hotbed of Know-Nothing sentiment: Joseph Barker, a street orator and future mayor, organized Pittsburgh rowdies to harass Catholics long before Bedini's visit. Bishop Michael O'Connor urged his priests to wear inconspicuous clothing to avoid violence, a precaution that availed little.

On December 11th, Bedini arrived at St. Patrick's Cathedral for service and a reception by Bishop O'Connor. While departing, a gang of toughs approached O'Connor, one offering the Bishop his hand. When O'Connor grasped it, the man rudely accosted him and peppered the clergymen with slurs. Trying to defuse the situation, O'Connor joked that the man had surely drank too much, whereupon the nativist pushed the Bishop to the ground. Bedini and O'Connor retired to their carriage and sped away from the Cathedral to O'Connors residence, protected by police who held a mob at bay.

Bishop Michael O'Connor

This minor scuffle presaged far worse violence. In Cincinnati, natives formed unlikely alliance with German "Forty-Eighters." Usually suspicious of the latter's radicalism, Know-Nothings happily stoked their secular resentments against the "Butcher of Bologna." The German Society of Freemen outdid the most bigoted Nativists, decrying Bedini as "a butcher of men [who] offers to the patagonic cannibal the tears of poverty from sacrifice." Not content with scabrous language, they further sanctioned his assassination.A mob of 2,000 Cincinnatians, bearing banners reading "No Priests, No Kings, No Popery" and "Down with the Roman Butcher" and effigies of Bedini, did their best on Christmas Day. Captain Thomas Lukens, Chief of Cincinnati Police, headed off the mob as it approached Bedini's residence. Someone in the crowd fired at the police, leading Lukens to unleash his constables on the mob. A violent skirmish erupted, with police arresting sixty rioters and injured eleven; one died from his injuries.

Bedini defiantly remained in Cincinnati, visiting churches and monasteries the week following the riot. His subsequent visit to Cleveland passed without incident; Bedini followed advice not to visit Louisville, Kentucky. Archbishop John Baptist Purcell of Cincinnati wrote that "the wicked had been confounded" and that the worst seemed over. Then Bedini turned his gaze southward, triggering the next round of demonstrations.

In early January 1854, placards denouncing the Nuncio appeared in New Orleans, asking whether "This abominable servant of despoty [will] receive the same honors as the heroes of freedom?" and imploring Americans to "treat him as you would a wild beast." Archbishop Blanc considered rescinding Bedini's invitation, but the Cardinal anticipated his decision. He decided instead to return to New York, passing through Wheeling, Virginia (now West Virginia).

Yet again, Nativists anticipated the Cardinal's visit with pledges of bloodshed. "Do not disgrace your reputation by tolerating such a monster as Bedini in your midst!" an anonymous broadside urged. Bishop Richard Whelan implored Mayor Sobieski Brady for protection, but the Mayor professed his inability to act. Fearing violence against not only the Nuncio but Wheeling's Catholics, the Bishop took matters into his own hands.

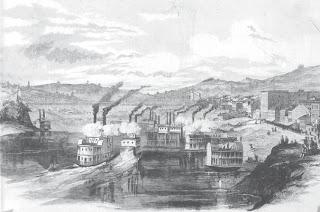

Wheeling ca. 1861

Bedini arrived in Wheeling on January 4th, spending several days at Bishop Whelan's residence and attending a banquet at St. James Cathedral. All seemed well until January 7th, when a Know-Nothing mob attacked the Cathedral, throwing stones and smashing windows. As the mob turned on Whelan's home, the Bishop summoned hundreds of armed Irishman, roused with fury to defend the Cardinal. Their assailants burned Bedini in effigy but engaged in no further violence, cowed by Whelan's promise to shoot anyone who threatened Bedini, his home or the Cathedral."Divine Providence has wished to test me once again here," Bedini wrote. "Thanks be to God, the night passed without disorder, but not without dangers." As he left Wheeling on January 9th, he narrowly escaped an assassination plot; a gang of toughs planned to kill him as he boarded his train. One conspirator evidently lost his nerve, informing authorities of the plot; he paid for his troubles when a compatriot stabbed him to death.

Bedini left Wheeling for New York and secretly departed the country a week later. His departure didn't quell the tensions he'd stirred. Bigots continued stirring the pot; one colorful crank, John S. Orr, traveled across the United States posing as the "Archangel Gabriel" in a flowing white robe. Throughout 1854, Orr incited violence in Boston, Pittsburgh and Nashua, New Hampshire; in some instances, mobs went straight from his sermons to attack churches and convents. After several arrests, Orr left the United States for British Guyana, inciting violence against that colony's Catholics.

Emboldened, the Nativists enhanced their extralegal violence with mainstream, open politicking. After decades of fits and starts, violent whispers and unplanned outbreaks of violence, what Carleton Beals calls "America's first fascist movement" coalesced into a national party. No longer operating in the shadows, the Know-Nothings took their case directly to the American people.

James F. Connelly's The Visit of Archbishop Gaetano Bedini to the United States of America: June 1853-February 1854 (1960) describes this incident in exhaustive detail. For general information, see the works by Anbinder, Beals, Billington and Myers cited in previous articles.

Previous articles on Know-Nothings and Nativists:

- The Charlestown Convent and the Birth of American Hate, 1834

- Philadelphia's Bible Battles, 1844