History records George Wallace (1918-1998) as the villain of America's greatest morality play, the Civil Rights Movement. While Wallace earned his reputation as America's leading segregationist, he's a more complex figure than allows. More calculating politico than committed racist, Alabama's Governor was a man of many faces.

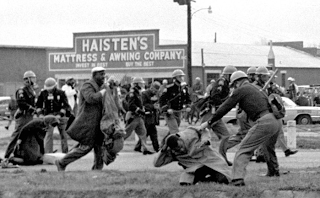

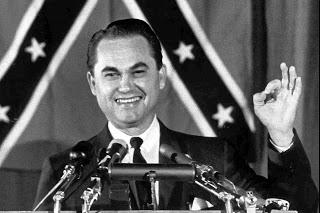

History records George Wallace (1918-1998) as the villain of America's greatest morality play, the Civil Rights Movement. While Wallace earned his reputation as America's leading segregationist, he's a more complex figure than allows. More calculating politico than committed racist, Alabama's Governor was a man of many faces.There was George Wallace, the embodiment of Southern racism. Whose inaugural address declared "Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!" Who defied Federal marshals acting to desegregate the University of Alabama. Who condoned the murder of civil rights activists. Whose State troopers attacked demonstrators in Selma on national television, without shame or regret.

There was Wallace the strongman. While decrying the Civil Rights Act as government overreach, he didn't mind spending Federal money on costly infrastructure and personal projects. He used Al Lingo's State Police to harass not only activists but political opponents with nocturnal visits and threatening phone calls. More than racism, one critic despised Wallace because "he brought fear to Alabama."

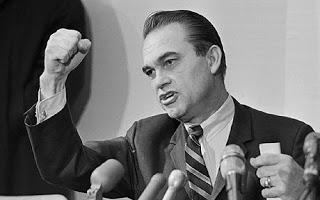

Playing the villain: Wallace in Tuscaloosa, June 1964

There was also the national Wallace. Outside Alabama, he seemed intelligent, genial and coolheaded. Interviewed by Meet the Press just before the University confrontation, Wallace insisted he merely intended to "raise constitutional questions that can then be adjudicated by the courts." At Harvard, he disarmed Ivy League students with quick-witted answers. He easily reshaped bigotry into a plea for states rights and limited government.Martin Luther King, Jr. warned that "Wallaceism is bigger than Wallace," whose backlash message resonated outside the South. In 1964, Wallace challenged Lyndon Johnson in several Democratic primaries. He managed strong showings in Wisconsin, Indiana and Maryland. Wallace connected with working class whites, imbued with anticommunism, religious piety and racial resentment.

Morality play: violence at Selma, March 1965

Wallace's message, and King's fears, were soon vindicated. Race riots swept the country, hitting Watts, Newark and Detroit over the next few years. Whites responded in kind: when King visited Chicago in 1967 to support a garbage strike, he was attacked by white protestors. Northerners shocked by Southern violence towards blacks weren't so accommodating in their own backyards."The basic philosophy of the people all over this nation is similar," Wallace commented. "I receive just as enthusiastic a response to my message in Oregon, or in the State of Washington, or in California as I do in Alabama." In 1968, he proved it with another presidential campaign, this time heading the American Independent Party.

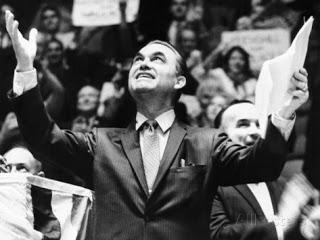

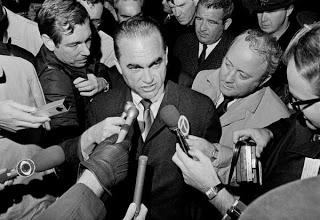

Sending a message: Wallace in Pittsburgh, February 1968

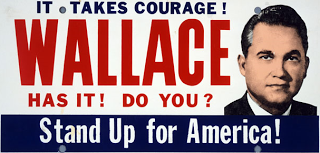

To head his campaign, Wallace assembled a colorful coterie of cranks. There was Asa Carter, Klansman-turned-novelist (his Gone to Texas inspired The Outlaw Josey Wales) and speechwriter. Or George Mangum, music producer-turned-advance man. Or Reverend Alvin Mayall, chairman of Wallace for President, whose anti-Semitic tirades disgusted even Wallace. They conjured a suitably patriotic slogan, "Stand Up for America."Wallace also attracted right wing celebrities, from actors Walter Brennan and Chill Wills to musicians like The Oakridge Boys and Wally Fowler. John Wayne, who publicly endorsed Nixon, discreetly donated to Wallace's campaign. As did millionaire H.L. Hunt, Robert Welch of the John Birch Society and other reactionary businessmen. He also benefited from the Democratic Party's implosion.

In 1968, the Democrats were divided over Vietnam. Antiwar Senators Eugene McCarthy and Robert Kennedy drove President Johnson from the race; Vice President Hubert Humphrey took the Establishment's mantle. Spring and summer of 1968 brought divisive primaries, Kennedy's assassination, a Chicago convention marked by violence outside and backroom chicanery within. Disaffected Democrats, left and right, looked for new homes.

Message received: Wallace supporters in Ohio

As in 1964, Wallace connected with working class whites, North and South. In Boston, he turned out 50,000 supporters; 20,000 crowded Madison Square Garden in New York. Race riots following Martin Luther King's death in April increased the urgency of his appeal. Hunter S. Thompson compared a Wallace rally to a "Janis Joplin concert," with less drugs and more Confederate flags.Supporters deluged his Montgomery headquarters with calls, donations and letters. A trip through Mississippi in June yielded $450,000 in donations; a single day in Texas netted $35,000. A campaign film, The Wallace Story, aired on CBS and NBC in August: "The money is just coming in by the sack fulls!" a campaign worker marveled afterwards. Wallace netted $9,000,000 in grassroots donations, nearly as much as Humphrey.

And Wallace also found unexpected support. Many disillusioned McCarthy supporters joined Wallace's campaign to protest Humphrey. Even fringes of the counterculture supported Wallace; Hippies for Wallace emerged in Albany, New York, encouraging supporters to "Freak Out With George." One hippie told an incredulous reporter, "Wallace is straight, man. He tells it like it is."

Wallace in New York, October 1968

And why not? Wallace's mix of populism and resentment had an appeal beyond racists and rough-necks. He fused hatemongering with attacks on Big Government and Big Business, boogeymen for Americans of all stripes. Pete Hamill, writing in Ramparts, declared that "the only one of the three major candidates who is a true radical is Wallace.”The mainstream press couldn't fathom Wallace. They mocked his ramshackle campaign operations, consuming peanuts and Dr. Pepper on Wallace's plane. "If I had been with the campaign another week or two, I could have been appointed to press secretary," said journalist Richard Cohen. Cohen also sneered at Wallace for not "ris(ing) above the lower middle class background in which he was raised."

If Wallace resented their condescension, he also manipulated them. He joked with reporters about his coarseness: "Y'all be sure to get a shot of me shaking my fist, or picking my nose," before obliging them. David Braater called Wallace "my favorite bigot," a sentiment many endorsed. With his raucuous oratory and unrestrained pronouncements, Wallace made good copy.

Wallace, pressed by the press

"It's a sad day when you can't talk about law and order unless they want to call you a racist," Wallace complained. "I never have in my public life... made a speech that would reflect upon anybody because of race, color, creed, religion or national origin." But Wallace's imprecations against black rioters and student protestors were easily decoded, and inspired his most extreme supporters.Violence surrounded Wallace, which he openly encouraged. "We don't have riots in Alabama," he told one crowd. "They start a riot down there, first one of 'em to pick up a brick gets a bullet in their brain." During applause lines he'd step back from the podium, remove his jacket and shadowbox, relishing the moment. In this atmosphere, rhetoric inevitably bled into reality.

Wallace events attracted thousands of protestors. Many hurled invectives; others threw eggs, rocks and sandals. Wallace supporters responded in kind, attacking hecklers with signs, chairs, sticks and fists. In New York, police fought a Wallaceite mob to rescue three black men. Protestors shouted "Sieg heil!"; supporters denounced them as "Commie faggots!" Then they came to blows, turning the rally into a riot.

Wallace's America: violence in New York, October 1968

Even Wallace's staff grew scared; they'd receive midnight phone calls from supporters, rambling about blacks, Jews and liberals. Tom Turnipseed, Wallace's campaign manager, angered a Massachusetts supporter when he said that Wallace wouldn't round up blacks and shoot them. Turnipseed also angered Montana's campaign chairman, who'd been expelled from the John Birch Society as too extreme.Still, through the summer Wallace polled at over twenty percent, nearly even with Humphrey. Then in September, Humphrey defied Johnson by endorsing withdrawal from Vietnam. The AFL-CIO purged the "Wallace Infection" in union ranks with a massive PR campaign. Liberals and blue collar Democrats, reassured, belatedly endorsed Humphrey's campaign; Nixon's lead narrowed, Wallace's support withered.

Wallace also gave Richard Nixon cover for his Southern strategy, wooing Southerners to the Republican Party. While Nixon deplored Wallace's tone, his rhetoric was remarkably similar. "Let us recognize the first civil right of every American is to be free from domestic violence," he intoned, his campaign ads showing footage of crime and riots. If Wallace's overt bigotry had limited reach, Nixon's masked appeals proved effective.

Richard Nixon: mainstreaming resentment

The death blow came with Curtis LeMay, ex-Air Force General and Wallace's running mate. At a Pittsburgh press conference, LeMay attacked America's "phobia" towards nuclear weapons. As Wallace watched, open-mouthed, LeMay commented "I would use anything we could dream up" to win Vietnam. If America feared anything more than racial tension, it was nuclear war.As Nixon and Humphrey's contest became a horse race, Wallace imploded. Still, he managed 13.5 percent of the popular vote, winning five Southern states (Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana and Mississippi) and 46 electoral votes. Though Ross Perot outpolled him in 1992, Wallace remains the last third party candidate to score with the Electoral College.

Wallace ran again in 1972, now as a Democrat to "send them a message." His campaign ended when Arthur Bremer, a deranged drifter, shot and paralyzed him. By then, Nixon's capture of the "Silent Majority" was complete: he won a 49 state landslide against Democrat George McGovern. Resentment towards racial violence, antiwar protests and angry leftists entered the mainstream.

Wallace and Nixon, 1972

In 1970, Wallace defeated Alabama Governor Albert Brewer with undisguised bigotry. One ad depicted a white girl menaced by black brutes: "This could be Alabama in four years!" it screamed. "Do you want it?" Wallace later recanted, appealing for racial tolerance and forgiveness. He seemed sincere, campaigning with Civil Rights leader John Lewis and receiving heavy black support in later campaigns. But Wallace remained controversial until his death in September 1998.Wallace was an expert showman: where does man end and poseur begin? Upon losing his first gubernatorial campaign in 1958, Wallace supposedly said he'd never be outdone on racism again. As Governor, he was more Huey Long than Jefferson Davis, a benevolent dictator who supported welfare and poverty relief but couldn't tolerate dissent. But he consciously made racism part of his image; lifetime notoriety was the consequence.

Sincere or not, Wallace's campaign had a lasting impact on American politics. He expertly packed racial resentment, populist appeals and personality cult into a crude but effective package. In 1968, 9.9 million Americans sent a message that reverberates with us still.

This article draws on Dan T. Carter's The Politics of Rage (1995), a phenomenal biography which charts Wallace's career, message and impact. Stephan Lasher's George Wallace: American Populist (1994) was also helpful. For the 1968 campaign, see Lewis Chester, Godfrey Hodgson and Bruce Page's An American Melodrama (1969) and Rick Perlstein, Nixonland (2008).

Previous articles:

- Nelson Rockefeller and the Demise of the Liberal Republican

- William Scranton for President, 1964

- William Scranton for President, 1964, Part Two