America's intervention in Siberia

Picture a scene from a John Buchan or Ian Fleming thriller: a general, summoned across country without notice, arrives at a train station where he's contacted by a strange man wearing a red hat. This crimson contact takes the General to a side room to meet the Secretary of War, who assigns him a top-secret mission to a nation wracked with civil war. He hands the General a sealed envelope bearing instructions from the President of the United States, and departs with a foreboding epigram: "Watch your step: You will be walking on eggs loaded with a dynamite."Major General William S. Graves, decorated veteran of the Filipino-American War and member of the Army General Staff, experienced this incredible scenario in August 1918. His meeting with Secretary of War Newton Baker left him frustrated: he expected to join the fighting in France, and instead found himself opening another theater of Woodrow Wilson's undeclared war against Soviet Russia. His mission, if possible, proved even more muddled than the Polar Bears in Arkhangelsk; at least they could identify their enemy.

The confusion was entirely Wilson's fault. Like many liberal presidents, he harbored an instinctive squeamishness towards military force, disguising it in idealistic rhetoric and limited goals. Thus his maddeningly vague aide-memoire to Graves, where he concluded "that military intervention there would add to the present sad confusion in Russia rather than cure it," while advising Graves to secure the Trans-Siberian Railway and rescue the Czechoslovak Legion (a corps-sized conglomerate of Slavic soldiers organized by Tsarist Russia) stranded in Siberia.

William S. Graves

"I read this document several times and tried to analyze and get the meaning of each and every sentence," Graves wrote later. He chose to interpret Wilson's instructions as literally as possible: in effect, he would carry out a peacekeeping mission in Siberia, helping to stabilize a region torn by conflict and foreign intervention, without involving himself on either side. Still, Graves worried "why I was not given some information about what was going on in Siberia." Perhaps if Graves had been, he might have tried to decline his mission.The Russian Far East had descended into chaos. Dozens of small-scale anti-Bolshevik governments sprung up in seemingly every town in city; many moderate Mensheviks, others monarchists, a small few democratic. Red partisans and Cossack freebooters pillaged the countryside, killing, burning and looting indiscriminately under the banner of Bolshevism or a Tsarist restoration. Which isn't to mention the Czechoslovak Legion, who had seized most of the Trans-Siberian Railroad in fighting with local Bolsheviks, and needed rescue less than a route to their homeland.

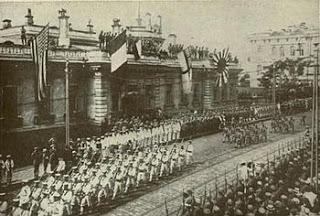

Besides the Czechs, other powers had arrived in the Far East since March 1918. Japan landed its first troops in Vladivostok to retaliate against the murder of four sailors; soon 70,000 Japanese troops flooded the region. The British and French maintained smaller military missions, partly to help the anti-Communist Whites and partly to constrain their ambitious Asian ally. Token forces of Chinese, Italian, Polish and Serbian troops also operated in the region. It was a hodgepodge of conflicting powers with wildly different motives, united only in a general revulsion towards Communism.

Allied troops in Vladivostok

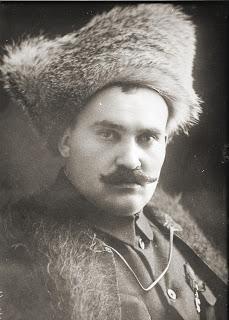

The first elements of Graves' command, the 8th Infantry Division, arrived in Vladivostok in mid-August, weeks before their commander. The Americans, troops of the 27th Regiment from Manila, received an immediate taste of future troubles: General Otani, the Japanese commander, shanghaied several companies into a raid against Bolshevik forces along the Trans-Siberian. While seeing little combat themselves, the Americans were chagrined at Japanese highhandedness and appalled by their brutal tactics. Private George Billick scoffed of these dubious allies, "I'll bet they'll give us more trouble than the Russians before we are through."Indeed, Graves spent most of his early months in Vladivostok wrangling with his supposed colleagues. He found General Otani an affable man but convinced, without proper authority, that he commanded all Allied troops in the region. One of Otani's lieutenants issued a proclamation, declaring "the Japanese Army...the real savior of the Russian people" but also warning that Japan would "invoke a severity of action" against anyone who resisted them. The Japanese also bankrolled Gregory Semenov, a Cossack freebooter whose depredations against Bolsheviks, Jews and neutrals disgusted even his allies.

The British commander, Sir Alfred Knox, made his own power play in Omsk, which housed the Imperial gold reserves. Dismayed that Russia was becoming "Mexico in the midst of frost and snow," Knox decided that a strongman was preferable to dozens of anti-Bolshevik splinter groups. He settled on Admiral Alexander Kolchak, a sailor and Polar explorer who had spent the year since the Revolution abroad, looking for employment. With assistance from Knox's troops, Kolchak ousted the Socialist government in Omsk in November, declaring himself Supreme Leader of All Russia.

Kolchak (second from left) with Radola Gajda (left), commander of the Czech Legion

Initially reluctant to take power, Kolchak promised that“I shall follow neither the path of reaction nor the fatal course of partisan politics. My main objective will be to organize an effective army to triumph over Bolshevism.” Noble words aside, he settled comfortably into his role, instituting a dictatorship as inefficient as it was brutal. His men slaughtered anyone perceived as enemies, especially Jews who were Russian reactionaries' favorite target. That he relied on foreign bayonets, especially the Czechs, weakened his standing with other White leaders, who declined to recognize his regime.While Kolchak prepared for a westward offensive towards Moscow, Graves tried to carry out his mission. His troops substituted for Czechs and other allies along the Siberian Railway; they engaged in frequent skirmishes with Red partisans and armored trains, but rarely the pitched battles that their Polar Bear colleagues experienced. They also came to blows with their nominal allies: American and Japanese patrols fought at least once, while Lt. Col. Robert Eichelberger, Graves' intelligence chief, was arrested by Cossacks for interrupting their burning a village.

Gregory Semenov

It was Semenov, the Cossack warlord, who brought matters to a head. In May 1919, a confrontation between American troops and drunken Cossacks resulted in the shooting of a Cossack corporal. In response, Semenov demanded a railroad car from the Americans, his men seizing it at gunpoint when refused. On another occasion, a fistfight between one of Semenov's captains and an American private led to a shootout which left the Russian dead and the American injured. Repeated requests by Graves to the Japanese to restrain Semenov fell on deaf ears.The most calamitous incident occurred on June 10th when Lt. Col. Charles Morrow, commanding the 27th Infantry, confronted a Cossack armored train at the Verkhne-Udinsk station. When Morrow refused to let the Cossacks through, a Japanese patrol intervened. Their commander told Morrow that unless the Americans backed down, the Japanese would fire on them. Morrow, whom Graves described "a fellow with a short fuse already lit," responded by leveling several cannon at the Japanese forces. The confrontation continued for several minutes until the Cossacks grudgingly backed their train out of the station.

Meanwhile, American troops along the railway faced almost daily confrontations with Bolsheviks. Usually minor raids, occasionally the confrontations grew more serious. At the village of Kraefski on June 12th, two squads of the 27th Infantry came under attack by nearly 150 Bolsheviks. Heavily outnumbered, the Americans repulsed the attack with disciplined, close-range rifle fire; John Evans, a cook, won the Distinguished Service Cross for killing nine Bolsheviks singlehanded. The Bolsheviks dubbed the ferocious 27th the "Wolfhounds," a moniker they bear to this day.

Troops of the 31st Infantry, on patrol near Vladivostok (source)

Life in Vladivostok wasn't much better. Flooded with refugees and foreign soldiers, streets flowing with garbage and stray animals, it lacked charm. While their colleagues fought Bolsheviks (and occasionally Whites) in the hinterland, American troops in the city found criminal activity and political instability equally vexing. Captain Rodney Spring of the 31st Infantry complained that "twenty-four hours never pass without the report of at least two or three violent deaths." Attempts at curbing the violence through an international police force met marginal success.Soldiers in the city, at least, had access to creature comforts like alcohol and women; venereal diseases proliferated among garrison soldiers. Those unlikely enough to serve along the railroad dealt with bitterly cold temperatures, outbreaks of flu and other diseases, and the ever-present danger of enemy attacks - whoever the enemy might be. Letters home were inevitably censored, if forwarded at all. One of Graves' aides, Captain Kenneth Roberts, reported that "most of the participants in the Siberian Expeditionary Force seemed semi-insane with cold, idleness and the depression that accompanies these two curses."

All the while, General Graves insisted that "the United States is not at war with the Bolsheviki or any other faction in Russia." His efforts at neutrality, however well-intended, frustrated everyone. Sir Alfred Knox criticized him for refusing to back Admiral Kolchak, whom Knox felt "has energy, patriotism and honesty." Others accused Graves of Bolshevism; a rumor spread that his men were New York Jews, recruited to undermine the Allied war effort. Even Graves' own government challenged him: one War Department staffer, responding to his telegrams, chastised Graves for "not sending the kind of information out of Siberia we want you to send."

Troops at the front (source)

Belatedly, there were efforts at inter-allied cooperation. The so-called Railroad Agreement signified specific sectors for different Allied commands; Graves intercepted arms to Semenov, generating Japanese protests but no active resistance; the Cossack, momentarily chastened, made a promise, or at least a show, of restraint. But it was too late; Admiral Kolchak suffered decisive defeats in the Urals, the new Czechoslovak government clamored for their legion to return home, and Bolshevik forces massed in Siberia. For all but the most oblivious observers, the writing was on the wall.Nonetheless, through the summer and fall of 1919 Americans conducted their largest campaign of the war. Suchan (now Partizansk), north of Vladivostok, harbored some of Russia's largest coal mines; it also harbored a large contingent of Bolsheviks under Sergey Lazo, a 25 year old cavalryman. Throughout the past year, Lazo's men had murdered Whites, Japanese and miners with impunity. Graves dispatched Colonel Frederick H. Sargent, with five companies of the 31st Infantry, to clean out the region. The Americans seemingly succeeded through May and June, but the Bolsheviks retained enough force to strike back.

On June 25th, a platoon of Company A encamped at Romankova, well behind Sargent's unit. Before dawn, Lazo led 150 Red partisans through the brush, firing into the American camp. They called for the Americans to surrender, then machine gunned those who tried. The surviving Americans, led by Lt. Lawrence Butler, fought their way to the cover of log houses. Two Americans with Browning automatic rifles, Emmet Lunsford and Roy Jones, shot down dozens of Bolsheviks, while other braved enemy fire to retrieve ammunition from the camp. By the time Lazo's Reds withdrew, 19 Americans had died and 26 were wounded.

Sergey Lazo

With support from American naval forces, Japanese troops and White Russian allies, Sargent continued the campaign through August, killing or capturing hundreds of Bolsheviks: at its end, Colonel Williams of Graves' staff could boast that "the Suchan Valley is practically free of Bolsheviki." The campaign's success was a credit to the officers and men taking part, but did little to change the course of events.By November 1919, Kolchak had been decisively defeated and Omsk overrun. The Czechs, tired of acting as pawns to the Great Powers, captured Kolchak and turned him over to the Bolsheviks in exchange for free passage home. On February 7th, 1920, Kolchak was executed, a once-honorable man destroyed by power. Graves, for one, didn't mourn his passing: "I doubt if history will show any country in the world...where murder could be committed as safely and with less danger of punishment than in Siberia during the regime of Admiral Kolchak."

These events assured the departure of Americans. General Graves began concentrating his forces in Vladivostok in January 1920, while detachments of the 27th Infantry continued rearguard actions along the Trans-Siberian Railroad. Evacuations continued through April, when Graves finally departed with his staff. In a sardonic commentary, Japanese troops lined the docks as a band played "Hard Times Come Again No More."

Kolchak reviewing troops (source)

The Japanese lingered for a few more months, attempting to grab territory amidst the chaos. As the Reds consolidated power in Siberia, their position became untenable and they, too, withdrew. General Semenov fled abroad, lived a confused, vagabond life, spending time in China and the United States, supporting Japan's Manchukuo puppet state before being executed at the end of World War II. Many of his Cossacks remained and joined Baron Ungern von Sternberg's quixotic quest to conquer Mongolia until May 1921.The Russian Civil War was over, and Graves, his men and the Allies had little to show for their efforts. Bruce Lockhart, a British diplomat, commented that the intervention "raised hopes which could not be fulfilled. It intensified the civil war and sent thousands of Russians to their deaths." Others, watching the Soviet Union's descent into barbarism, felt differently. Robert Eichelberger, Graves' chief of intelligence, regretted "that we did not put more troops into Siberia for the purpose of defeating the Reds."

Japanese troops in Vladivostok (source)

In their way, both men were right. Despite the depredations of Kolchak, Semenov and other White leaders, overthrowing Communism in its early stages might have spared Russia and the outside world millions of lives and decades of grief. Its execution, however, was halting and compromised, limited and ill-considered, enough to earn Russian enmity but not to make a positive impact. Men like Graves, Knox and even Otani could only achieve so much in such absurd circumstances.General Graves, who received heavy criticism for his conduct and comments on the campaign until his death in 1940, offered a sardonic summary in his memoirs. "The absence of information from the United States and the Allied Governments about military intervention in Russia," he wrote, "indicates that the various Governments taking part in the intervention take very little pride in this venture. Who can blame them?" Who indeed?

This article draws upon: William S. Graves, America's Siberian Adventure, 1918-1920 (1931; online here); W. Bruce Lincoln, Red Victory: A History of the Russian Civil War (1989); Richard Luckett, The White Generals (1971); and Robert L. Willett, Russian Sideshow: America's Undeclared War, 1918-1920 (2003).

Other articles on World War I, the Russian Intervention and the Age of Wilson:

- The American Polar Bears Meet the Bolsheviks

- The American Protective League and the War on Slackers, 1917-1919

- The Eastern Front, 1914-1917 (1975, Norman Stone)

- The Guns of August (1962, Barbara W. Tuchman)

- The Hun's Shadow in America, 1917-1918

- Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I (2014, Alexander Watson)

- The Siege (1970, Russell Braddon)

- Somerset County's Men of Iron in the Great War