Woodrow Wilson was a man of contradictory impulses. He enacted progressive economic and labor reforms while racially segregating the Federal government. He spoke stirringly about spreading democracy abroad while suppressing civil liberties and arresting dissidents at home. He advocated national self-determination while authorizing military adventures in multiple hemispheres. Perhaps Wilson's most troublesome foreign crisis concerned Mexico, which spent the 1910s wracked with revolution and civil war.

Woodrow Wilson was a man of contradictory impulses. He enacted progressive economic and labor reforms while racially segregating the Federal government. He spoke stirringly about spreading democracy abroad while suppressing civil liberties and arresting dissidents at home. He advocated national self-determination while authorizing military adventures in multiple hemispheres. Perhaps Wilson's most troublesome foreign crisis concerned Mexico, which spent the 1910s wracked with revolution and civil war.In 1910 an alliance of urban liberals and rural bandits overthrew Mexico's ancient, reactionary dictator Porfirio Diaz. His successor, Francesco Madero, instituted democratic and land reforms which led to a ferocious backlash. Ultimately, Victoriano Huerta, a scheming general known as "the Jackal," betrayed Madero to his enemies, seizing power himself in February 1913. In this, he had the support of American Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson, who boasted that "I have overthrown this government."

Appointed by William Howard Taft, the Republican Ambassador Wilson preferred a Mexican strongman who'd reestablish order to reforms that endangered American lives and corporate investments. Woodrow Wilson, on the other hand, was a progressive Democrat appalled by Huerta's bloody coup and brutal repression of his opponents. "We can have no sympathy with those who seek to seize the power of government to advance their own personal interests," Wilson proclaimed.

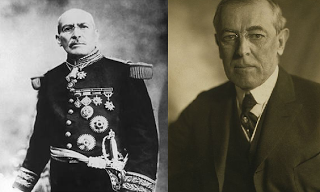

Victoriano Huerta (left) and Woodrow Wilson

High-minded sentiments aside, Wilson proved reluctant to force the issue. He imposed an arms embargo against both Huerta and his rival, Venustiano Carranza, while attempting to negotiate free elections without Huerta's involvement. His peacemaking efforts angered both sides: Huerta asserted that Mexico would "try and perform our task" without America, while Carranza warned that Wilson's meddling "will awaken a profound hatred between the United States and the whole of Latin America." Only Pancho Villa, warily allied to Carranza, remained favorable to Wilson.So Wilson dithered, announcing a policy of "watchful waiting" while keeping troops and warships on alert along the border. That other powers took an interest in Mexico - Britain, infuriated by Villa's murder of landowner William Benton; Germany, who covertly armed Huerta - further stilled his hand. Not until April 1914, as Carranza and Villa's forces inflicted crushing defeats against Huerta's armies, did Wilson find an excuse to intervene directly. All over a remarkably trivial incident, dubbed by one historian as "an affair of honor."

On April 9th, 1914, nine sailors from the USS Dolphin arrived in Tampico, a Mexican port city north of Veracruz. With Carranza's forces nearing the city's outskirts, local authorities were on high alert. After a brief scuffle, a local official arrested the sailors at gunpoint and marched them to the local jail. Rear Admiral Henry T. Mayo, commander of the Dolphin's squadron, demanded a formal apology and a twenty-one gun salute by the Mexican navy. Huerta's government agreed to apologize, but found the latter demand outrageous.

Wilson, who felt "oppressed with the thought that he might be the cause of the loss of lives of many young men," initially tried to downplay the incident. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan insisted that "Admiral Mayo...will regard the apology as sufficient." But Mayo did not, ordering more warships and Marine detachments into the region. Accepting the Admiral's precipitate action, Wilson now demanded that "the salute will be fired." Huerta offered a reciprocal salute between American and Mexican warships, but Wilson refused.

USS Dolphin

Despite his initial reticence, Wilson seized upon the Tampico Affair to oust Huerta. On April 20th, seeking congressional authorization for military action, he insisted that "our quarrel was with Huerta, not the Mexican people" (a formulation he revisited when declaring war on Germany three years later). The following day, Wilson learned that the Ypiranga, a German cargo ship, had left Cuba en route for Veracruz with a cargo of small arms. This steeled his resolve to act, even though Congress hadn't yet formally approved his proposal.Rear Admiral Frank F. Fletcher's small naval detachment - the battleships Florida and Utah and the gunboat Prairie - was America's man on the scene. Fletcher had only about 1,200 sailors and Marines at his command, though he was reinforced at the last minute by an additional Marine regiment numbering about 1,100. Fletcher's men had been stationed in the region for several months, enjoying what leisure they could in the sweltering heat. Then at 8:00 am on April 21st, Fletcher received a terse wire from the Navy Department: "Seize custom house. Do not permit war supplies to be delivered to Huerta government or any other party."

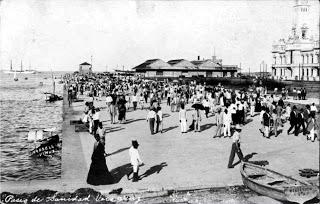

Mexico's oldest city and largest port, Veracruz in 1914 was both picturesque and repulsive. Its beautiful waterfront and scenic appeal (backdropped by Pico de Orziba, Mexico's highest mountain) vied with oppressive heat and tropical squalor. Thanks to neglect by local authorities, the city lacked proper sanitation, leaving the streets filled with stagnant water, garbage and human waste. Vultures and dogs fought for scraps, while outbreaks of yellow fever and cholera scourged its population.

Veracruz in 1914

Given his limited objectives, Fletcher hoped to avoid bloodshed. The Admiral enlisted William Canada, America's counsel in Veracruz, to negotiate the city's surrender. Canada phoned Mexican General Gustavo Maass, commanding the city's defenses, calling upon him not to resist the landing. Maass shouted "No, it cannot be!" and hung up on Canada. Civil authorities, fearing retribution, refused to cooperate with the Americans as well.A vain, strutting officer who modeled his appearance on Kaiser Wilhelm, Maass had only about 600 regular troops under his command. He organized a militia force, the Society of Defenders of the Port of Veracruz, 300 civilians armed with obsolete Winchester rifles. He also opened the city's jails and conscripted the prisoners in exchange for freedom. (Many simply deserted rather than fight.) Though heavily outnumbered and of decidedly mixed quality, Maass could force the Marines to engage in costly urban warfare.

Meanwhile, Admiral Fletcher assembled his men in the harbor, blue-jacketed Marines and sailors sporting rifles and machine guns. He noted ominous gray clouds in the sky, sharks swimming in the harbor and vultures circling the waterfront. At 11:20 am, the first American landing parties, about 700 men under Marine Lt. Colonel Buck Neville, splashed ashore. They encountered hostile glares from Mexican civilians, and armed bands of Mexican soldiers, but managed to secure the waterfront and reach their objectives without bloodshed. For about half an hour, it was a textbook operation.

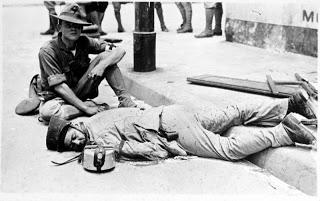

Marines under fire

Then, at 11:57 am, a shot rang out, and a Navy signalman who'd climbed atop the Terminal Hotel fell, dead. Captain W.R. Rush, commanding the Naval brigade, spotted a large body of Mexican troops - he claimed it was 1,000 men, though probably far fewer - approaching the waterfront. He signaled Fletcher, who ordered the Utah to dispatch its forces in support. Heavy fire erupted from all sides, and the Battle of Veracruz began.Major Smedley Butler, one of the Marine Corps' most decorated officers, recalled their nightmarish reception. "Mexicans in the houses, on the roofs and in the streets peppered us from all directions. Some fired at us with machine guns." Butler and others initiated savage street fighting, with Marines blasting their way through barricades and clearing out houses and municipal buildings that were honeycombed with snipers. With assistance from Fletcher's naval guns, the Marines gained a foothold on the north side of Veracruz.

Rush's Naval brigade found it rougher going. With little combat experience, they marched through the streets in close-order movements, presenting easy targets for Mexican riflemen. At least three signalmen shared the fate of their colleague, shot down while trying to wigwag messages from Rush to Fletcher. Supply officers trying to bring ammunition ashore also came under fire; one officer, a Boatswain McCloy, wrangled several small one-pound guns from the fleet and exchanged fire with the sharpshooters until naval guns destroyed their hiding spot.

Admiral Fletcher

Even with such high-caliber help, the landings soon bogged down. Neither the Marines nor the sailors made much progress after the initial fighting, and Fletcher faced the prospect of drawn-out urban warfare. Unbeknownst to the Americans, however, General Maass received an order from Huerta's Defense Ministry to abandon Veracruz. The General grudgingly complied, withdrawing his regulars but leaving several hundred militia behind. Throughout the night the latter rampaged through Veracruz, firing on the Americans and Mexican civilians in the dark.Having lost four killed and twenty wounded in the day's fighting, Admiral Fletcher again tried for a peaceful resolution. William Canada tried contacting the city's mayor and other officials, who had either gone into hiding or refused his offer to surrender. As April 22nd dawned, with Neville and Rush's men steeled by Marine reinforcements, Fletcher issued a directive: "Advance at your discretion, and suppress this desultory firing, taking possession of the city and restore order."

The Marines launched the main assault. Seasoned in counterinsurgency tactics from fighting in China, the Philippines and Latin America, they commenced targeting snipers in building-to-building searches. "We advanced under cover, cutting our way through adobe walls from one house to another," Butler reported. "We drove everybody from the houses and then climbed up on the flat roofs to wipe out the snipers." Another witness reported Marines using machine guns "like fire hoses," mercilessly spraying alleyways and occupied buildings with lead. Using these tough but effective tactics, Butler and Neville managed to clear most of the city with few casualties.

Sailors in combat

Meanwhile, Rush's sailors again suffered from their inexperience. Captain E.A. Anderson, commanding one of Rush's regiments, marched his men along the edge of town at port-arms, in parade-ground order. He refused advice to send out scouts to reconnoiter, dismissing the chance of serious resistance. "It showed a rare stupidity scarcely credible in the circumstances," historian Robert Quirk writes. As they approached the Naval Academy, Anderson was rudely awakened. His men received a volley of rifle fire from the Academy, where forty teenage cadets (including Jose Azueta, son of a Mexican commodore) and militiamen stationed themselves.Hidden behind mattresses and mealy bags, the cadets inflicted several casualties on Anderson's men while remaining impervious to return fire. Anderson's men panicked, with many fleeing into the streets while their dumbfounded commander stood, bullets crashing into the pavement around him. Again the sailors relied on naval fire to rescue them; Fletcher's heavy guns obliterated the Academy and all of its defenders with a few minutes of concentrated shellfire. Jack London, writing for Colliers magazine, compared the display to "Buffalo Bill's exhibits of rare shooting."

By noon, all serious resistance had ended. In two days of fighting, the Americans lost 22 men killed and 70 wounded. Mexican casualties aren't certain, but an American naval surgeon recorded 126 dead and 195 wounded. Much of the city lay in ruins, reduced to rubble by artillery and machine gun fire, along with the Marines' destructive tactics.

Remains of the Naval Academy

Within a few days, Fletcher's force was reinforced by an Army task force under Brigadier General Frederick Funston. A decorated hero of fighting in Cuba and the Philippines (where he had captured guerrilla leader Emilio Aguinaldo), Funston drafted ambitious plans to march on Mexico City and oust Huerta, replicating Winfield Scott's campaign in 1847. He was chagrined when Wilson refused to authorize such an expedition, instead settling into a long military occupation.Over the next seven months, Funston worked to improve daily life in Veracruz. His men cleaned the streets of garbage and refuse, drained stagnant water pools and modernized the city's sewage system. The annual yellow fever outbreak didn't happen, disease plummeted and the omnipresent vultures virtually disappeared. One historian, perhaps overstating things, termed the occupation "the best government the people of Veracruz ever had." Which didn't stop Mexicans generally from resenting the gringos: even the most benevolent foreign occupiers breed resentment.

Initially, the expedition united Mexicans of all stripes against Wilson. "The offense the Yankee government is committing against a free people...will pass into history," warned General Huerta. Carranza condemned the invasion as violating Mexican sovereignty. Anti-American riots raged across Mexico from Tampico to Baja California. Only Pancho Villa seemed pleased, encouraging General Funston to "keep Veracruz and hold it so tight that not even water could get in to Huerta." (Ironically enough, though the Americans intercepted the Ypiranga, German arms shipments continued unabated.)

Smedley Butler (left) and Frederick Funston

Losing several battles to Villa and Carranza, Huerta abdicated on July 15th and fled to Texas. Yet the American occupation dragged on, earning resentment both abroad and at home. Cyrus L. Sulzberger, an American businessman, complained that "If the President must back up every Admiral, there is no reason why we should not get into war with every country having a seaport." Others, both military and political, called for renewed military operations. Senator William Borah of Idaho declared the Veracruz occupation "the beginning of he march of the United States to the Panama Canal."Wilson had no interest in such naked imperialism and little more for bloodshed. He accepted the offers of the so-called ABC Powers (Argentina, Brazil and Chile) to mediate a dispute between the US and Mexico, agreeing to redress damages and insults. Soldiers in Veracruz grew restless, resenting their superiors' lassitude and desiring action. A young Captain named Douglas MacArthur led a raid into the interior, capturing three railroads and engaging Mexican cavalry in a shootout.

Finally, on November 23rd the Americans evacuated the city. Hoping to put a brave face on the occupation, Wilson authorized 55 Medals of Honor to be awarded to various participants, mostly officers. Not all appreciated the honor. Smedley Butler, for one, considered winning the Medal for such a tawdry exploit an insult and attempted to return it. Not only was Butler's request denied, he received orders to wear it publicly from his superiors This incident, along with future service in Latin America, converted Butler from war hero to avid pacifist.

Sailors from the USS Florida

Mexico remained in turmoil for almost a decade afterwards. Carranza and Villa soon fell out, initiating another round of violence that ultimately triggered further American intervention. In March 1916 Villa, angered at Wilson's withdrawal of support, launched a raid against Columbus, New Mexico which left 52 dead. Wilson dispatched John Pershing to capture Villa; Pershing failed, but did manage again to unite Villa and Carranza, albeit briefly, against foreign interlopers. Eventually Carranza was overthrown by Alvaro Obregon, whose ascension to power in 1920 finally stabilized Mexico as a functional democracy.Meanwhile, Woodrow Wilson struggled to learn from this fumbled affair. He continued his ambivalent posture towards Mexico, retaliating against attacks on Americans but refusing to invade outright, sewing resentment to little benefit. The following year he sent Marines to occupy Haiti, instituting a brutal occupation that lasted until 1934. In the waning days of World War I (where he at least committed full-bore intervention), he authorized two undersized, ill-equipped expeditions against the newborn Soviet Union, which were similarly ineffectual.

Like many Democratic Presidents, Wilson felt a queasy ambivalence about projecting American power. Thus he launched bungled, ill-considered interventions wrapped in noble justifications, but lacking the force, will or direction to succeed. Hence Wilson's adventures in Latin America and Russia, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson maiming Vietnam, Bill Clinton's cruise missiles and Barack Obama's drone strikes, all of which generated more resentment than tangible results. Pity American servicemen and foreign soldiers and civilians alike who die for an impotent gesture.

This article draws upon: Max Boot, The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power (2002); John S.D. Eisenhower, Intervention! The United States and the Mexican Revolution, 1913-1917 (1993); and Robert E. Quirk, An Affair of Honor: Woodrow Wilson and the Occupation of Veracruz (1967).

Other articles on the Age of Wilson:

- The American Polar Bears Meet the Bolsheviks

- The American Protective League and the War on Slackers, 1917-1919

- The Eastern Front, 1914-1917 (1975, Norman Stone)

- General Graves and the Siberian Shuffle

- The Guns of August (1962, Barbara W. Tuchman)

- The Hun's Shadow in America, 1917-1918

- Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I (2014, Alexander Watson)

- The Siege (1970, Russell Braddon)

- Somerset County's Men of Iron in the Great War