April 8th, 1975 in Los Angeles, California. A massive thunderstorm swamped the Academy Awards, inundating the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion and its Hollywood elites with rain and misery. This particular Oscar night, however, would become better-known for the fireworks inside the theater, the culmination of a decade of protests paralleling a divided America.

April 8th, 1975 in Los Angeles, California. A massive thunderstorm swamped the Academy Awards, inundating the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion and its Hollywood elites with rain and misery. This particular Oscar night, however, would become better-known for the fireworks inside the theater, the culmination of a decade of protests paralleling a divided America.Some were relatively innocuous, like Rod Steiger proclaiming "We shall overcome!" after winning 1967's Best Actor for In the Heat of the Night. Others were more controversial, as when Marlon Brando sent Indian activist Sacheen Littlefeather to collect his Oscar for The Godfather in solidarity with Indian militants besieged at Wounded Knee. Some were simply childish, like artist and gay activist Robert Opel streaking across the stage in 1974. Any point beyond showsmanship was lost as presenter David Niven joked about Opel "stripping off and showing his shortcomings."

There seemed no reason for the 47th Academy Awards to be any different. The nation still reeled from the Watergate affair, with President Gerald Ford losing public favor after pardoning Richard Nixon. Worse, the Vietnam War reached a terminal stage, as North Vietnam launched its climactic invasion of the rickety south. With Indochina on the verge of Communist domination, the Academy rushed out a curious line-up of stars that seemed a rebuke to antiwar passions that helped bring it about.

Bob Hope

Bob Hope was a dependable Silent Majority warrior, beloved for his strong, uncomplicated patriotism and flag-waving USO tours. Frank Sinatra, onetime pal of John F. Kennedy and bleeding heart liberal, had become a hardline conservative, golfing with Spiro Agnew and denouncing student protestors. Fellow Rat Packer Sammy Davis Jr. was America's most prominent black Republican, after hugging Nixon onstage during the Republican National Convention three years earlier. Shirley MacLaine, erstwhile George McGovern fan and antiwar activist, provided a token leftist.Most of the evening unfolded without incident. The main awards became a duel between Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather, Part II and Roman Polanski's Chinatown. Coppola's film won the lion's share of the awards, scoring six Oscars to Chinatown's one, though Art Carney surprised everyone by winning Best Actor for Harry & Tonto. Hope quipped that he sported a bulletproof cummerbund to guard against retaliation from Al Pacino, nominated for Coppola's movie. Jack Nicholson, also nominated (for Chinatown), sat in stony silence and refused to congratulate Carney.

The shock came from Nicholson's longtime friend and collaborator, Bert Schneider. Schneider had, along with Bob Rafelson and Steve Blauner, funded BBS, an independent outfit which produced some of the era's edgiest independent films. From the bizarre Monkees vehicle Headand Dennis Hopper's counterculture epic Easy Rider, to Rafelson's muted character study Five Easy Pieces, Schneider's productions sat on the cutting edge of New Hollywood, thumbing their nose at established studio mores.

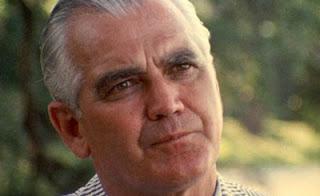

Bert Schneider (right) with Candice Bergen

Lately, Schneider had increasingly drifted towards the radical Left. He became a friend and benefactor of Huey Newton, helping the Black Panther leader escape to Cuba following a murder charge, and befriended antiwar activist Abbie Hoffman. While producing Hearts and Minds, his documentary on the Vietnam War, he referred to the movie as "a disaster epic," a powerful indictment of American intervention in Southeast Asia.Schneider teamed with Peter Davis, a young documentarian who'd shot "The Selling of the Pentagon," an expose of Defense Department public relations campaign, for CBS. The network's refusal to turn over outtakes and damaging footage led to a showdown with Congress, who attempted to cite CBS President Frank Stanton for contempt. Stanton defended the documentary before the House of Representatives, convincing them that television broadcasts constituted free speech.

Initially, Davis and Schneider contemplated a documentary on the Pentagon Papers and the ongoing trial of Daniel Ellsberg. Barred from filming the trial, Davis decided to think big: "I have a chance here to do something much grander if I can just figure out how not to get lost in the whole [issue] of Vietnam." Throughout 1972 and early 1973, as the American phase of the war wound down, Davis and his crew filmed extensively throughout America and South Vietnam, intercutting original footage with archival film and interviews.

The result is an extraordinary masterpiece. There had been earlier Vietnam documentaries (notably Emile de Antonio's The Year of the Pig) which came and went without much impact. Though Hearts and Minds initially saw little release, it helped define America's image of the war.

The result is an extraordinary masterpiece. There had been earlier Vietnam documentaries (notably Emile de Antonio's The Year of the Pig) which came and went without much impact. Though Hearts and Minds initially saw little release, it helped define America's image of the war.Hearts and Minds tells, through a succession of searing images and interviews, the history and impact of American intervention in Vietnam. The movie lacks a narrative through-line, flitting through events and topics non-chronologically, though several figures recur throughout the narrative, including Lt. George Coker. A POW for seven years, Coker's shown touring the country, hosting parades and giving speeches where he assures listeners "If it wasn't for the people, [Vietnam] was very pretty" and that the Vietnamese are merely "backward."

This provides an entrée to the movie's major theme. Juxtaposing scenes of wartime atrocity, and GI's own words, with footage from classic Hollywood movies (including a Bob Hope comedy!) and propaganda films, Hearts and Minds demonstrates the crude blend of patriotism and casual racism driving American policy in Vietnam. They view the Vietminh as Soviet puppets rather than a native Communist movement, making Vietnam a test of American resolve. Too bad that "test" falls upon the Vietnamese people, unwittingly caught in the crossfire.

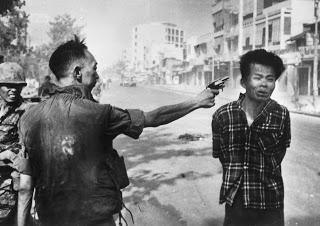

What's stunning is the disconnect between American idealism and the almost casual violence dealt to the country. We're treated to the famed images of a Vietcong prisoner's summary execution or a napalmed little girl fleeing her burning village. Pilots boast of their technical skill in flying bombers while Vietnamese testify to the destruction that American bombs and defoliants wrought. GIs burn hootches with zippo lighters and destroy villages with flamethrowers. It's an appalling sight that undercuts any high-blown rhetoric about democracy.

What's stunning is the disconnect between American idealism and the almost casual violence dealt to the country. We're treated to the famed images of a Vietcong prisoner's summary execution or a napalmed little girl fleeing her burning village. Pilots boast of their technical skill in flying bombers while Vietnamese testify to the destruction that American bombs and defoliants wrought. GIs burn hootches with zippo lighters and destroy villages with flamethrowers. It's an appalling sight that undercuts any high-blown rhetoric about democracy.It's impossible to maintain the casual fiction about "dinks" and "gooks" not valuing human life when Davis shows their victimization. The filmmakers visit several villages leveled by American bombs, families slaughtered and mutilated. A man capitalizes off the tragedy by building coffins; another who's lost his daughter suggests that the filmmakers take his daughter's shirt and throw it in Richard Nixon's face. These scenes bolster Daniel Ellsberg's contention that "We weren't supporting the wrong side; we were the wrong side."

Similarly the portrait of American exploitation. Foreign companies do business in Saigon, and South Vietnamese business leaders hold swanky lunches while their countrymen starve. One Saigon entrepreneur proudly describes himself as a "war profiteer" who hopes to promote tourism. Several vignettes show American GIs soliciting Vietnamese prostitutes; a lengthy montage runs through ineffective puppet rulers, from Ngo Dinh Diem through Nguyen Van Thieu, each upheld by their American benefactors as a strong defender of freedom, each unable to keep their country intact.

While Davis interviews American leaders and war supporters, we aren't given any reason to respect their perspectives. It's hard to tell how much of the interviewees' comments are staged or sincere, since we're only given one side of a conversation. One critic notes that the film "ignores anything showing Americans and South Vietnamese in a positive light. And you won’t find one frame even hinting that the North Vietnamese or Viet Cong were anything but heroic fighters whose only goal was national unification." Viewers can share Hearts and Minds' view that Vietnam was a disaster without finding it an objective portrayal.

While Davis interviews American leaders and war supporters, we aren't given any reason to respect their perspectives. It's hard to tell how much of the interviewees' comments are staged or sincere, since we're only given one side of a conversation. One critic notes that the film "ignores anything showing Americans and South Vietnamese in a positive light. And you won’t find one frame even hinting that the North Vietnamese or Viet Cong were anything but heroic fighters whose only goal was national unification." Viewers can share Hearts and Minds' view that Vietnam was a disaster without finding it an objective portrayal.However one-sided, Hearts and Minds isn't unsympathetic to the soldiers. One isn't shocked that Davis gives pride of place to the Vietnam Veterans Against the War, but even his everyday GIs receive rounded treatment. Most affecting, perhaps, are Randy Floyd, who describes being indoctrinated by anticommunist propaganda, but lost faith after dropping antipersonnel bombs on Vietnamese civilians. Or the assorted veterans we watch fitted for prosthetic limbs or wheelchairs. The parents of a deceased pilot defend his actions and even praise President Nixon (presumably an unintentional laugh line, as a subtitle reminds us these scenes were filmed in 1973).

In any case, the most damning moments speak for themselves. Walter Rostow mocks Davis for wanting to recount the war's origins, instructing the director to scrap this footage before snapping into sage pundit mode. Even worse are William Westmoreland's musings about the "Oriental's" view that "life is cheap," brutally intercut with images of Vietnamese wailing at a military funeral. Davis has commented that Westmoreland repeated these same comments through multiple takes, perfectly encapsulating the pigheadedness that characterized American folly in Indochina.

William Westmoreland

Failing initially to land an American distributor, Hearts and Minds found an enthusiastic audience at the Cannes Film Festival. Columbia offered to distribute the movie, until the inevitable backlash began. Walt Rostow demanded that Davis and Schneider reedit his interviews to show him more favorably, suing the filmmakers; Lyndon Johnson's advisors wanted them to cut footage painting the late President in an unflattering light. A judge shrugged off their complaints and allowed Hearts and Minds an American release.Columbia, however, backed out of distributing the film. Eventually, Schneider brought it to Warner Bros., who gave it an extremely limited initial release (mostly restricted to Los Angeles) in late 1974. Conservative and veterans groups protested the movie, even trashing one theater which hosted an early screening. Warners executive John Calley shrugged off these attacks, hoping to vindicate the movie at the Oscars.

Back to April 1975. Presenters Laura Hutton and Danny Thomas presented the documentary award, with Davis and Schneider walked onstage to applause. Davis provided a conciliatory message, bemoaning the ongoing conflict and the division it generated, but thanking his family and urging comity. Schneider, on the other hand, launched into a diatribe about the impending "liberation" of South Vietnam, then whipped out a telegram from North Vietnamese diplomat Dinh Ba Thi:

"Please transmit to all our friends in America our recognition of all that they have done on behalf of peace and for the application of the Paris Accords on Vietnam. These actions serve the legitimate interest of the American people and the Vietnamese people. Greetings of friendship to all the American people."

As Hutton and Thomas presented the award for Best Documentary Short, a violent row erupted backstage. Frank Sinatra confronted Schneider and threatened to deck him, with John Wayne (honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award earlier that night) joining in. Bob Hope pinned Howard W. Koch, the show's producer, to a wall, screaming for him to disavow the statement. Then Shirley MacLaine and her brother Warren Beatty leapt into the fray. "Don't you dare!" MacLaine shouted at the frazzled producer, caught in the midst of a Hollywood culture war.

As the stars squabbled, phone calls and telegrams began reaching CBS. One came from a retired Army Colonel, who bemoaned the "55,000 dead young Americans in defense of freedom and millions of Vietnamese fighting for freedom," then concluded with "demand withdrawal of award." Hope grabbed the telegram, scribbling a message for Frank Sinatra to read onstage.

As the stars squabbled, phone calls and telegrams began reaching CBS. One came from a retired Army Colonel, who bemoaned the "55,000 dead young Americans in defense of freedom and millions of Vietnamese fighting for freedom," then concluded with "demand withdrawal of award." Hope grabbed the telegram, scribbling a message for Frank Sinatra to read onstage.When Sinatra emerged, he stiffly read Hope's disclaimer. "The Academy is saying we are not responsible for any political utterances on this program and we are sorry that had to take place." Which provoked more outrage from his liberal costars. Warren Beatty mockingly commented "Thank you, Frank, you old Republican!" while MacLaine hissed that "You didn't ask me!" about the statement. MacLaine later retook the stage, encouraging viewers to see Hearts and Minds (a particularly gracious gesture, since it defeated MacLaine's own documentary, The Other Half of the Sky).

Eventually, Warner Bros. executives tried defusing the controversy with apologetic press conferences. Shirley Maclaine told reporters that "Bob Hope is so mad at me, he's going to bomb Encino," while Francis Ford Coppola defended Schneider's statement. The Silent Majority continued barraging CBS with hostile messages, but it seemed moot. Saigon fell within a matter of weeks, relegating the Academy arguments to a bizarre, angry footnote.

Despite its clunkier passages and one-sided polemics, Hearts and Minds has endured. It inspired a generation of activist documentaries, from Errol Morris (The Fog of War, The Corporation) to Michael Moore, who cited the movie as an inspiration for his Fahrenheit 9/11, and caused his own Oscar controversy by attacking George W. Bush in early 2003, just before the Iraq War. To those bemoaning politicization of the Oscars, we might reasonable wonder when they weren't political.

Despite its clunkier passages and one-sided polemics, Hearts and Minds has endured. It inspired a generation of activist documentaries, from Errol Morris (The Fog of War, The Corporation) to Michael Moore, who cited the movie as an inspiration for his Fahrenheit 9/11, and caused his own Oscar controversy by attacking George W. Bush in early 2003, just before the Iraq War. To those bemoaning politicization of the Oscars, we might reasonable wonder when they weren't political.