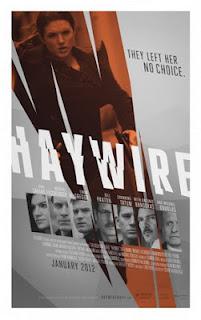

Haywire displays nearly all the traits of a modern Steven Soderbergh movie. It sports an A-list cast seemingly game for anything. It jet sets all over the world even though it hardly needs to, suggesting that the director A) insists on verisimilitude, B) loves studio-paid vacations, or C) both. Its shallow-focus digital cinematography creates paranoid, claustrophobic frames of doubt and suspicion; Haywire even opens with such abstracted, zoomed-in pixellation that the text telling the audience they're watching upstate New York simply must be a gag. And as with the cast of Bubble and Sasha Grey in The Girlfriend Experience, Haywire features a non-professional actor anchoring the action, in this case retired MMA fighter Gina Carano.

Haywire displays nearly all the traits of a modern Steven Soderbergh movie. It sports an A-list cast seemingly game for anything. It jet sets all over the world even though it hardly needs to, suggesting that the director A) insists on verisimilitude, B) loves studio-paid vacations, or C) both. Its shallow-focus digital cinematography creates paranoid, claustrophobic frames of doubt and suspicion; Haywire even opens with such abstracted, zoomed-in pixellation that the text telling the audience they're watching upstate New York simply must be a gag. And as with the cast of Bubble and Sasha Grey in The Girlfriend Experience, Haywire features a non-professional actor anchoring the action, in this case retired MMA fighter Gina Carano.The film also works as the latest in Soderbergh's never-ending line of genre deconstructions. Despite its lean running time of 93 minutes, Haywire leaves gulfs of space around its revenge plot, Lem Dobbs' script asymptotically approaching exposition, only to flatline in vagueness before reaching it. Dobbs, of course, wrote the screenplays for Soderbergh's Kafka and, somewhat infamously, The Limey. Given the amount of dialogue, it stands to reason more of Dobbs' words remain here than in Soderbergh's masterfully elliptical anti-thriller, but Haywire nevertheless shares many qualities with the director's best film. Both are action thrillers that dismantle the conventions of their niches within the genre, finding beauty and agony in the all-too-single-minded attitudes of so many of these films.

Soderbergh and Dobbs frame Haywire as a constant series of glancing blows to coherence. Beginning near the end, the film shows a shivering, antsy Mallory Kane (Carano) walking into a diner in aforementioned upstate New York and enjoying but a moment's peace before Aaron (Channing Tatum) pulls up and instantly sets her on edge. They exchange half-spoken details of a mission in Barcelona and Aaron urges her to come with him. When she declines, he throws coffee in her face and the two proceed to get in a vicious, visceral fight in front of stunned onlookers. Mallory gets the upper-hand with the help of an intervening patron (Michael Angarano), then takes the young man hostage and drives away in his car. While riding, she explains how she got there as the film promptly moves to flashbacks to follow her narrative.

The frequent time jumps become just another way to constantly stay ahead of explaining what, exactly, is going on. Slowly, the film pieces together that Mallory was the top contractor in a private sector firm farming out mercenaries for American black-ops missions. We see the mission in Barcelona alluded to earlier, as well as her betrayal at the hands of her employer and former lover, Kenneth (Ewan McGregor, whose perennial youthfulness makes the idea of the government turning to him for national defense even funnier).

Though he subverts as more tropes than he faithfully portrays, Soderbergh makes one of the more engaging and felt action films of the last few years. He holds his shots out in the fight scenes, cutting judiciously to keep momentum while nevertheless giving the audience a refreshing visual continuity and flow. He didn't hire a trained MMA fighter to be in the lead just to cut around her, and it's thrilling to see Carano take and give blows without all the erratic, stunt-double-hiding editing that defines so many modern fighting movies. This also gives her a screen presence that more than makes up for her stiff line readings, which would throw off the flow of the film in Soderbergh wasn't already doing that so casually with his structure.

Indeed, the director finds other ways to disorient the viewer accustomed to the current slate of beat-em-ups in the absence of shakycam editing. Camera angles constantly find unorthodox framings, while the placement of the camera in fight scenes is, amusingly, farther away and more objective than in the more blurred static moments. There's also the score by Ocean's series composer David Holmes, who brings a similarly jazzy touch to the music here. As Carano runs after a loose end in Barcelona, the exertion and determination on her face is deliberately undermined by the light tone of the music running over the scene. But Holmes' score is no less propulsive and textured than Soderbergh's alternately chugging and lethargic direction. It's the perfect compliment to a strange film, capable of capturing the disparate, often conflicting moods Soderbergh layers into his deconstructive film.

Holmes even offers some clues to what Soderbergh might be doing here in occasionally throwing back to the music of old spy movies. Haywire, more than a mere martial-arts movie, is also a take on the spy thriller. Perhaps the fact that Mallory is not a government agent but a private contractor hired by a government explains the breaks in genre routine. It's not Soderbergh tearing apart this genre, it's the cynical progress of our national defense strategies. McGregor schemes with officials (Michael Douglas and Antonio Banderas), who in turn plot against him when the time comes. In the new world of intelligence and classified assignments, the only goal seems to be to cover one's ass and maybe make a profit if at all possible. Though the pieces eventually come together to reveal who betrayed Mallory and how everyone else she's encountered fell into place, Haywire still leaves disturbingly vague just what it is these people do when they're not trying to kill one of their own.