Book Review by Sylvia D: I decided to read Hatter’s Castle for the Scottish and Welsh session, because, apart from the treatment of its women characters, Cronin’s The Citadel was a good read with a strong message. Hatter’s Castle was his first novel and couldn’t be more different from The Citadel. It is 600 pages long and the long-winded, flowery opening sentences were a real turn off. However, I persevered albeit with the aid of frequent skip-reading.

This is a story of arrogance and tyranny with James Brodie, the hatter, eventually destroying his family and himself.

The picture on the front of my paperback is misleading as he is a huge, muscular man, a brutal, selfish, arrogant bully who dresses immaculately, is a stickler for punctuality and frequently resorts to verbal and sometimes even physical abuse. He isn’t very intelligent. He has built up a flourishing business over the past 20 years but now leaves the day to day running of the shop to his assistant, rather sickly, lanky Peter Perry with a wart on his nose who is rather good with the customers. Brodie spends most of the day in his office reading the Glasgow Herald so he can discuss current affairs knowledgeably with other members of the literary and philosophical society, dealing with suppliers and only appearing in the shop when a high-class customer arrives.

The Castle is the architecturally eclectic house Brodie lives in which he designed himself against all advice and is totally oppressive, ugly and comfortless. His colleagues in his town of Levenford in the Scottish Lowlands south of Glasgow snigger about the house behind his back.

At home he is a tyrant, expecting his wife to wait on him hand and foot. He is perpetually sneering at and belittling her and she in turn is desperate to please and desperately afraid of him. He has three children, an older, self-possessed daughter called Mary whom he has forced to leave school and has cut off from other young people, a rather weak son, Matthew, who is pampered by his mother and his favourite, very bright younger daughter, Nessie, who is rather fragile. He is always ambitious for her and expects her to be top of her class.

Mary, naïve and sexually unaware, is secretly seeing a young man, Denis Foyle, and one evening she slips out to go to the fair with him and by what seems to be a process of osmosis becomes pregnant.

Then her mind was dazzled, and, as she lay with closed eyes in his embrace, she forgot everything, knew nothing, ceased to be herself, and was his. Her spirit rushed to meet his swifter than a swallow’s flight and together uniting, leaving their bodies upon the earth, they soared into the rarer air. Together they floated upwards as lightly as two moths and as soundlessly as the river. No dimension contained them, no tie of earth restrained the ecstasy of their flight.

Denis asks Brodie if he can marry Mary but ambitious Brodie, horrified at the thought of her marrying an Irishman whose father is a publican even though Denis himself is making a successful career as a traveling salesman, threatens him physically. In the ensuing fracas Denis gets the better of Brodie for which he is never forgiven. Mary manages to hide the pregnancy for seven months but then goes into early labor. Her mother realises her condition and petrified that Brodie will blame her for Mary’s lapse, betrays her daughter to her father. He casts her out on a wild night and, coatless, she faces a nightmare journey in the dark, wind and rain before she finds shelter in a cattle byre where, by now almost unconscious, she gives birth. She is found by the old woman who owns the byre and the local, handsome, young doctor Renwick is summoned. In true Victorian style, the baby dies, Mary gets pneumonia and, when recovered, runs off to London to become a servant. On the same night as the baby was born, Denis loses his life in the Tay Bridge disaster.

Son, Matthew, has been courting the daughter of a local shopkeeper and Brodie, thinking she isn’t good enough for his son, wangles a job for him in Calcutta in the offices of the local ship-building company. After two years, Matthew returns in disgrace having developed a taste for wine, women and partying and neglected his duties. He cadges and steals money from his mother; she collapses and becomes bed-ridden with cancer of the womb. Brodie is starting to face business difficulties as a branch of a very dynamic and modern outfitters has opened next door to him and he is stubbornly refusing to make any improvements to his own shop. He starts to lose customers and then his assistant to the competition. He takes to drink and seeks solace in the arms of Nancy, a local barmaid, who moves in as house-keeper when his wife dies. Matthew eventually finds a job and Nancy, whom Brodie seems to feel for in a funny sort of way, runs off with him to start a new life in South America. Nessie, desperate at the thought of being left on her own with Brodie, writes to Mary and begs her to come home.

Brodie loses his business, he starts to drink more and more and becomes obsessed with the idea that Nessie should win a local scholarship which he discovers his hated enemy’s son is also going in for. Despite Mary’s endeavours he drives his daughter harder and harder and gets her to such a state that, when she discovers she has failed to win the scholarship, her mind goes and she commits suicide. Mary is carried off by the same handsome Doctor Renwick who saved her from pneumonia and Brodie, the victim of his own arrogance and cruelty, is left on his own except for the company of his old crone of a mother who has crept malevolently throughout the story getting increasingly blind, deaf and demented.

Compared with The Citadel, Hatter’s Castle feels very Victorian. It is full of melodrama, the writing is convoluted and flowery. Events are unnecessarily drawn out and become tedious. The section on the build up to Nessie taking the scholarship exam seemed interminable. The language is very repetitive. I lost count, for instance, of the number of times Cronin expressed Brodie’s insolence with the words ‘sneer’, ‘jeer’ and ‘leer’. There is much Scottish dialect but very little sense of place. It could have been set virtually anywhere. Arguably, the characterisation is strong but overdone and there are a few successful set pieces such as when Brodie closes his shop for the final time and tosses all his remaining stock out to passersby in the street. The story might have benefited from a really ruthless edit but I doubt it would have made much difference.

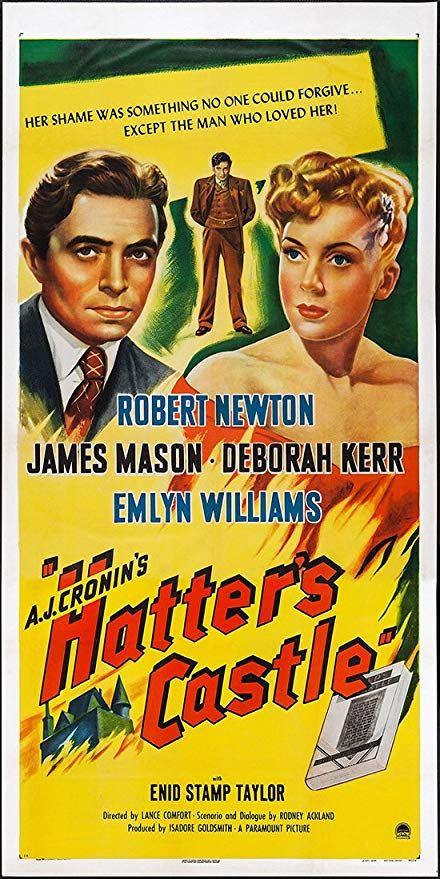

The book was made into a film in 1942 with Robert Newton as Brodie, Deborah Kerr as Mary and James Mason as Dr Renwick. Only the bare essentials of Cronin’s novel were used in the film even though Cronin himself was one of the scriptwriters.